How the Journey Began

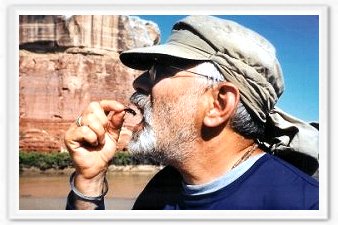

Eating bugs in the Canyonlands

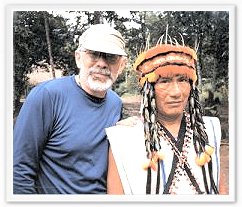

I have long had an interest in wilderness survival, and I have been trained in mountain, desert, and especially jungle survival, which took me on a number of trips to the Upper Amazon, both for training and to study indigenous survival techniques. I helped bring health care to remote Amazon villages with the Rainforest Health Service; I was one of a group who made the first descent by raft of the Puyango-Tumbes River. One of these trips, with wilderness survival expert Ron Hood, to study the jungle survival skills of the last of the headhunting Shapra and Candoshi Indians, became an award-winning survival training film.

But, as I learned more and more about the ways in which indigenous people survive — indeed, flourish — in the wilderness, it became increasingly clear to me that wilderness survival included a significant spiritual component — the maintenance of right relationships both with human persons and with the other-than-human persons who fill the indigenous world.

Thus I began to explore wilderness spirituality, to learn ways to live in harmony with the natural world, striving, like indigenous people, to be in right relationship with the plant and animal spirits of the wilderness.

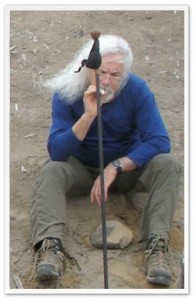

I undertook numerous four-day and four-night solo vision fasts in Death Valley, the Pecos Wilderness, and the Gila Wilderness of New Mexico. I worked with ayahuasca and other sacred plants in the Upper Amazon, peyote in ceremonies of the Native American Church, and huachuma in Peruvian mesa rituals. Out of this quest grew my deepening study of the shamanism of the Upper Amazon, which became the basis for Singing to the Plants.

Singing to the Plants is a result of my own need to make sense of the mestizo shamanism of the Upper Amazon, to place it in context, to understand why and how it works, to think through what it means, and what it has meant for me.

Here is a story. I am drinking ayahuasca. Suddenly I find myself standing in the entry hallway of a large house in the suburbs, facing the front door. The floor of the hallway is tiled, like many places in the ayahuasca world. There is a large staircase behind me, leading to the second floor; there are large ceramic pots on either side of the entrance way. I open the front door and look out at a typical suburban street — cars parked at the curb, traffic going by, a front lawn, trees along the curb. Standing at the door is a dark woman, perhaps in her forties, her raven hair piled on her head, thin and elegant, beautiful, dressed in a red shift with a black diamond pattern. She silently holds out her right hand to me. On her hand is a white cylinder, about three inches long, part of the stem of a plant, which she is offering to me.

With the Shapra Indians in the Amazon

I was concerned about this vision, because the red-and-black dress might indicate that the dark woman was a bruja, a sorceress. But don Roberto, my maestro ayahuasquero, and doña María, my plant teacher, both immediately and unhesitatingly identified her as maricahua, whom they also call toé negro, the black datura. They told me that this plant is ingested by splitting the stem and eating a piece of the white inner pith about three inches long. The lady in my vision was handing me just such a piece of the plant, a part of herself.

Ayahuasca teaches many things — what is wrong or broken in a life, what medicine to take for healing. It teaches us to see through the everyday, to see that the world is meaningful and magical; it opens the door to wonder and surprise. I need to open my front door, look out onto a bland suburban street, and see standing there the Dark Lady, the black datura — thin and dark, raven hair piled on her head, elegant and beautiful, silently holding out to me a stem of maricahua — and follow her into her dark and luminous world.