Explore Articles Filed Under: Sacred Plants

Daniel Mirante is a young — thirty years old, which is young to me — visionary artist, author, and researcher fascinated with deep ecology, shamanic traditions, ancient mythology, and the creative process. In 2000, he founded the well-known Lila website — the word lila means something like cosmic play in Sanskrit — as a creative collective and resource for people exploring what Delvin Solkinson of the Elfintome Arts Collective has called medicine culture — shamanic forms of creativity and healing, including plant-based entheogenic practices.

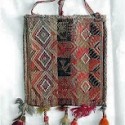

Chewing the leaves of the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca) plays a significant role in traditional Andean culture. Coca acts as a stimulant to overcome fatigue, hunger, and thirst. It is considered particularly effective against altitude sickness. It also is used as an anaesthetic to alleviate the pain of headache, rheumatism, wounds and sores. Coca leaf chewing is most common among indigenous communities across the central Andean region, particularly in the highlands of Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru, where the cultivation and consumption of coca is part of the national culture, and where sharing coca leaves is a powerful symbol of social and cultural solidarity.

I have always been a big fan of Terry Riley. I still have my original 1964 vinyl pressing of his In C, which burst on the classical music scene like a revelation — minimalist, aleatoric, melodic, haunting. His musical trajectory has carried him beyond minimalism to a sometimes startling eclecticism, but all his music is shimmering, luminescent, and beautiful. My teacher don Roberto Acho spoke of the singing of the plants as being puro sonido, pure sound; Riley writes, in the same sense, pure music.

In 1955, banker R. Gordon Wasson, an amateur connoisseur of mushrooms, was introduced by the Mazatec shaman María Sabina to the ancient teonanácatl — the Psilocybe mushroom, called ‘nti-ši-tho in Mazatec, Little-One-Who-Springs-Forth. María Sabina called them her saint children. Wasson was deeply impressed by his mushroom experience. He speaks of ecstasy, the flight of the soul from the body, entering other planes of existence, floating into the Divine Presence, awe and reverence, gentleness and love, the presence of the ineffable, the presence of the Ultimate, extinction in the divine radiance. He writes that the mushroom freed his soul to soar with the speed of thought through time and space. The mushroom, he says, allowed him to know God.

In the preceding two posts, I have argued that there is little convincing evidence that shamans outside the extended culture area of the Upper Amazon have ever used hallucinogens in their shamanic work; and, in the immediately preceding post, I argued against the belief that shamans in Siberia used the fly agaraic mushroom Amanita muscaria for shamanizing. There is also, I believe, little evidence for the shamanic use of psychoactive plants or mushrooms among the indigenous peoples of North America.

In the previous post, I claimed that hallucinogenic plants and fungi have been used in shamanism only in a particular culture area, radiating out from the Upper Amazon, primarily westward into the Andes, northward into Central America and Mexico, and eastward into Brazil. Claims to the contrary — that hallucinogen use underlies most shamanisms both diachronically and synchronically — often turn on the purported use of the hallucinogenic fly agaric mushroom Amanita muscaria by Siberian shamans.

Travel and exchange has occurred throughout the Western Amazon since long before the arrival of Europeans. What seems to the unfamiliar eye to be a vast undifferentiated landscape is in fact threaded with riverine highways navigable over long distances in dugout canoes. In addition to efficient canoe transport, indigenous people in the Amazon have always been able to cover long distances on foot, even carrying heavy loads, with remarkable speed. Anthropologists Blanca Muratorio and Michael Taussig have both provided nineteenth-century paintings and engravings that show indigenous porters carrying heavy burdens through the jungle highlands, including white men wearing frock coats and Panama hats, sitting on chairs strapped to the porter’s back.

Each doctor, each vegetal que enseña, each species of teaching plant has what mestizo shamans call a madre, mother, or genio, genius, or espíritu, spirit, or imán, magnet, or matriz, matrix. Informally, we generally translate all these terms simply as the spirit of the plant. In addition, mestizo shamans have a wide variety of protective birds and animals and plants, which we call, too, something like protective spirits. Yet, as Graham Harvey points out, those who are willing to argue endlessly about the meaning and applicability of the term shaman often refer to spirits as if everyone knows what the word means.

Once you begin la dieta, once you drink ayahuasca, once you begin to form relations of confianza with the healing plants, the world becomes a more dangerous place. Sorcerers resentful of your presumption will shoot magical pathogenic darts into your body, or send fierce animals to attack you, or fill your body with scorpions and razor blades — especially while you are still a beginner, before you gain your full powers.

Among ribereños in the Upper Amazon, there is a body of traditional lore regarding both the uses and the administration of a relatively large number of Amazonian medicinal plants. My jungle survival instructor, Gerineldo Moises Chavez, who made no claims at all to being a healer, knew dozens of jungle plant remedies, including insect repellants, treatments for insect bites, snakebite cures, and antiseptics. While mestizo shamans claim to have learned the uses and administration of their medicinal plants from the plant spirits themselves, it is also true that their uses of the plants are, in most cases, consistent with widespread folk knowledge about the plants.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa