Explore Articles Filed Under: Sacred Plants

Since at least the 1970s, a tenacious meme has circulated among a generally progressive youthful demographic, some of whom have now carried that meme with them into their elderhood. The meme states that there is a connection between our ecological crisis and our loss of earth-connected spirituality — a connection to both earth and spirit that we once possessed but have now lost, and which is still preserved for us by some indigenous peoples. Still, the meme says, there is hope. A spiritual awakening is coming, associated with the Age of Aquarius, or the fifth pachakuti, or the culmination of the Mayan calendar in the year 2012.

The documentary Fire on the Mountain: A Gathering of Shamans was filmed in 1997 at a ten-day gathering of tribal elders, wisdom keepers, and medicine women from five continents, who had travelled to Karma Ling, a Tibetan Buddhist retreat center in the French Alps, to discuss their concerns with the Dalai Lama and representatives of the world’s religions.

I have talked before about a 1996 study of long-time users of ayahuasca in the União do Vegetal church, which showed that drinking ayahuasca hundreds of times over decades of participation had no adverse impact on personality, and was in fact associated with significantly higher scores on measures of concentration and short-term memory. In 2005, a similar study of long-term peyote-using members of the Native American Church reported similar results.

Matthew Baggott is a graduate student in neuroscience at UC Berkeley and a research associate at California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute. He is interested in the mechanisms and effects of MDMA and hallucinogens, and in what they can tell us about the working of the brain and consciousness. His ongoing research includes measuring the cognitive, social, and emotional effects of MDMA, LSD, and methamphetamine in humans.

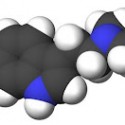

I want to think about three sacred plants — the ayahuasca drink, the peyote cactus, and the teonanácatl mushroom. These plants — well, actually, one of them is a fungus — are often discussed in terms of their — dimethyltryptamine, mescaline, and psilocybin respectively. Sacred plants such as these are commonly categorized by the chemical structure of their single active molecule. Thus peyote is categorized by the phenethylamine core of its mescaline molecule; ayahuasca and teonanácatl are categorized by the tryptamine cores of their dimethyltryptamine and psilocybin molecules.

We have talked about the use of snuffing tablets and snuffing kits among the ancient Tiwanaku in the Andes, such as the elaborate kit, shown at the left, that was buried with an adult male who appeared to have snuffing lesions near his nose. A recent archeological discovery, to be published in a forthcoming issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science, now suggests that such South American snuffing devices were considered valuable heirlooms, and were carried long distances and preserved for long periods of time.

Many researchers have studied the biochemical interactions through which ayahuasca produces its psychoactive effect. The current wisdom is pretty clear. The companion plant — chacruna, sameruca, chagraponga — contains the potent hallucinogen dimethyltryptamine, and the ayahuasca vine contains ß-carboline derivatives that inhibit the monoamine oxidase-A enzyme that inactivates of the dimethyltryptamine of the companion plant. Thus the ayahuasca drink is reduced to dimethyltryptamine, its single active molecule.

Tiwanaku is an important Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia. Tiwanaku is recognized by Andean scholars as one of the most important precursors to the Inca Empire, flourishing as the ritual and administrative capital of a major state power for approximately four hundred years between 700 and 1100 A.D. There has been good reason to believe that the inhabitants of Tiwanaku utilized an insufflated hallucinogen. They produced a variety of small carved objects that included puma and jaguar effigies, incense burners, and decorated wooden snuff tablets. Many mummies and skeletons from this culture were buried with such tablets and snuffing kits. One archaeologist reported recovering 614 snuffing kits from a single excavation.

The following, in three parts, is a documentary, originally created for French television, entitled Ayahuasca, the Snake and I, written and directed in 2003 by Armand Bernardi, narrated in English and with English subtitles. The film was produced by ArtLine Films, a well-known production company that coproduces documentaries and feature films with all the major French channels and with international broadcasters.

For those with an interest in sacred plants, the Fall 1989 issue of the Whole Earth Review holds a special place in our hearts. The issue is subtitled The Alien Intelligence of Plants, and it contains any number of delights — articles by Terence and Dennis McKenna; reviews of classic books on South American shamanism by Michael Taussig and Johannes Wilbert; articles on ethnobotany, plant intelligence, and the political economy of deforestation; and all of the small intriguing sidebar reviews and discussions that are characteristic of the Whole Earth style.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa