Explore Articles Filed Under: Research Studies

Do warfare and killing among Amazonian peoples have an evolutionary function? Anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon claims that the culture of the Yanomamö of Brazil exemplifies a key principle of sociobiology — that males who had murdered during intervillage warfare had more than twice as many wives and three times as many children as men who had not. In other words, he claims that violence is evolutionary adaptive behavior. Now a new study of violence and reproductive success, this time among the Waorani of Ecuador, has come to a different conclusion.

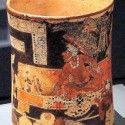

In 2001, a graduate student named Charles Zidar heard a lecture on the polychrome ceramics of the Classic Maya. The lecturer mentioned, in passing, that the botanical motifs with which many of these ceramics were decorated remained unidentified. This remark inspired Zidar, a natural historian and archaeologist, to focus his research on plants illustrated on Maya ceramics, culminating in the creation of a botanical resource database of the plants depicted in Classic Maya art, with the goal of rediscovering unknown or forgotten plants that were important to the ancient Maya. The initial results of this research have now been published.

Alexander Shulgin — familiarly known as Sasha — is a giant in the field of psychopharmacology, widely loved and admired for his inventiveness, courage, and sense of humor. He was a scrupulous and inventive chemist, and the creator of more than 230 psychoactive substances, most of which he tested on himself and on his wife Ann. For about four years now, Turn of the Century Pictures has been working on a documentary about Shulgin’s life and work. There is reason to believe that the film has evolved over the years. Where is it now?

The Moche culture flourished in the northwestern coastal areas of Peru around AD 100–800. Human sacrifice was a significant part of their state religion, apparently to appease a deity named Ai Apaec, who is depicted in Moche art as fanged, half-human, most often in the shape of a spider, holding in one hand a severed human head and in another the crescent-shaped ceremonial knife called a tumi. In the archeological literature, this deity has come to be called the Decapitator. Were hallucinogens part of these ceremonies?

Stanley Krippner, the Alan Watts Professor of Psychology at the Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center in San Francisco, is internationally known for his pioneering work in the scientific investigation of human consciousness, and especially of what he has come to call anomalous experiences — precognitive dreams, parapsychological phenomena, hypnosis, dissociation, altered states of consciousness, psychic surgery, and shamanism. Here is a thirty-minute interview with Krippner on the subject of ayahuasca, the “brutal teacher.”

We have talked before about the Grob, McKenna, Callaway, et al. psychiatric study on the long-term effects of drinking ayahuasca in the ceremonies of the União do Vegetal church. I noted that the study had not clearly disentangled any bias that might have resulted from the fact that the ayahuasca drinkers — but not controls — had been preselected for their orderly churchgoing habits. Here is a study that may shed some light on that question.

The Natufian culture flourished in the southern Levant between 15,000 and 11,600 years ago. One of the places that Natufian dead were buried is a small cave named Hilazon Tachtit, located on a steep cliff about 500 feet above the Hilazon River, with a sweeping view of the river and the Mediterranean shoreline, in which twenty-eight burials have been excavated. These burials can be dated to between 12,400 and 12,000 years ago, during the time that Natufian culture was in transition from foraging to farming.

No one knows how dimethyltryptamine causes its hallucinogenic effects. Dimethyltryptamine structurally resembles the tryptamine neurotransmitter serotonin. In fact, there is sufficient conformational resemblance between these two molecules that DMT can dock comfortably at serotonin receptors in the brain. Thus research to date has concentrated on serotonin receptors as the key to understanding DMT. But a recent study by Dominique Fontanilla and her colleagues at the University of Wisconsin, published this month in the prestigious journal Science, may change the direction of that research.

Northern Peru and southern Ecuador form a single culture area and share the same flora. Both are heirs of a regional plant healing tradition that goes back as far as the Cupisnique culture of the first millennium BC. But the two areas now show striking differences in plant knowledge and use. Plants used as medicine in southern Ecuador comprise only forty percent of the species used in northern Peru. Why is this?

How important is traditional plant knowledge in the Amazon? According to a recent study among the Tsimane’ in Amazonian Bolivia, each standard deviation of maternal ethnobotanical knowledge increases the likelihood of good child health by more than fifty percent. And the study raises the question: What will be the cost — to the Tsimane’ and other indigenous peoples — if such ethnobotanical knowledge is lost?

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa