Explore Articles Filed Under: The Medicine Path

Chewing the leaves of the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca) plays a significant role in traditional Andean culture. Coca acts as a stimulant to overcome fatigue, hunger, and thirst. It is considered particularly effective against altitude sickness. It also is used as an anaesthetic to alleviate the pain of headache, rheumatism, wounds and sores. Coca leaf chewing is most common among indigenous communities across the central Andean region, particularly in the highlands of Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru, where the cultivation and consumption of coca is part of the national culture, and where sharing coca leaves is a powerful symbol of social and cultural solidarity.

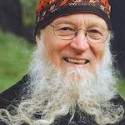

I have always been a big fan of Terry Riley. I still have my original 1964 vinyl pressing of his In C, which burst on the classical music scene like a revelation — minimalist, aleatoric, melodic, haunting. His musical trajectory has carried him beyond minimalism to a sometimes startling eclecticism, but all his music is shimmering, luminescent, and beautiful. My teacher don Roberto Acho spoke of the singing of the plants as being puro sonido, pure sound; Riley writes, in the same sense, pure music.

In December 1913, psychiatrist Carl Jung first experienced what he was later to call active imagination. However, he did not talk about these experiences until twelve years later, when, in May and June 1925, he spoke for the first time of his inner development at two sessions of a series of weekly seminars he was giving in Zurich. The contents of these lectures were not published until 1989; but a partial account of these experiences was given in 1962 by Aniela Jaffé in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, a purported autobiography of Jung which she largely wrote. This account is the foundation myth, the charter, for active imagination.

We reported earlier about efforts to maintain peyote populations in northern Mexico, in the sacred peyote grounds of the Huichol. A Reuters news service story yesterday by Jeff Franks tells a less hopeful story about the peyote harvest north of the border.

Speaking of endangered plant species, the government of San Luis Potosi in Mexico’s northern desert, working with the Huichol Indians and with Pedro Medellín, a professor at the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosi, is completing a plan for the protection of peyote, a plant that has been sacred to the Huicholes for hundreds and perhaps thousands of years.

Anthropologists who work with shamans and healers in indigenous cultures continue to be influenced by two significant cultural events — the impact of postmodernism on ethnography, and the brief apotheosis of Carlos Castaneda. These events challenged both prongs of the traditional anthropological concept of participant observation: postmodernism questioned what the fieldworker was observing, and Castaneda questioned whether the fieldworker was participating.

We have talked earlier about healing by sucking out the sickness — the phlegmosity, the pathogenic object, the dart that was projected into the patient by a sorcerer. But how does the shaman know where to suck?

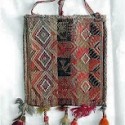

I am drinking ayahuasca. Suddenly I find myself standing in the entry hallway of a large house in the suburbs, facing the front door. The floor of the hallway is tiled, like many places in the ayahuasca world. There is a large staircase behind me, leading to the second floor; there are large ceramic pots on either side of the entrance way. I open the front door and look out at a typical suburban street — cars parked at the curb, traffic going by, a front lawn, trees along the curb. Standing at the door is a dark woman, perhaps in her forties, her raven hair piled on her head, thin and elegant, beautiful, dressed in a red shift with a black diamond pattern.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa