Explore Articles Filed Under: The Medicine Path

There are a number of human experiences that are characterized by presentness, detail, externality, and three-dimensional explorable spacefulness: we can call these visionary experiences. These can be characterized along two dimensions — according to the degree to which the experience is entered into intentionally, and by the amount of control the experiencer exercises over its content. Such visionary experiences appear to be quite widespread across cultures, and raise significant psychological and ontological questions.

At a meeting of the Native American Church, after a long night of singing and praying, the participants are served a sacred breakfast of small amounts of water, parched corn, and pemmican as the close of the ceremony. This is then followed by an informal breakfast where people eat, stretch their cramped legs, chat, and tell funny stories, often having to do with peyote and peyote ceremonies. James Howard, a professor at the University of North Dakota, calls these stories peyote jokes.

In an ayahuasca ceremony, we deliberately ingest something vile; we forcefully eject the contents of our bodies. The body is turned inside out, its boundaries transgressed. Our body becomes, in the word of literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, grotesque — fully embodied, porous and protuberant, part of the earth, exuberant and fecund. For the patient as for the shaman, to drink ayahuasca is to be connected to the body in profoundly physical ways.

Opening the door to the magical world is not a day trip. Every approach we make to the spirits entails reciprocal obligations. What those obligations are is a matter between each of us and the spirits, but at the very least they require gratitude and humility — a willingness to be courageous and vulnerable, to speak honestly from our hearts and listen devoutly with our hearts, to tell the spirits our truest stories

Significant materials in the field of Mesoamerican ethnomycology have been newly collected and translated by Brian P. Akers in his book The Sacred Mushrooms of Mexico: Assorted Texts. The work presents classic scholarship, previously unavailable in English, on Matlatzinca, Mixtec, Mixe, and other Mesoamerican sacred mushroom rituals — rich and detailed accounts of the place of psychoactive mushrooms in the lives of the peoples who use them. Plus a bonus — a classic 1960s television show.

The plant Salvia divinorum has a long and continuing tradition of use by Mazatec shamans, who drink it, sometimes followed by a drink of tequila, to induce visionary states during healing sessions. Popular use of Salvia, especially among young people, has been increasing — along with calls for its criminalization. Some medical researchers argue that scheduling the drug should wait until evidence about its effects and toxicity becomes clear. A recent article in Scientific American addresses the issues.

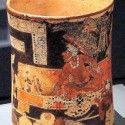

In 2001, a graduate student named Charles Zidar heard a lecture on the polychrome ceramics of the Classic Maya. The lecturer mentioned, in passing, that the botanical motifs with which many of these ceramics were decorated remained unidentified. This remark inspired Zidar, a natural historian and archaeologist, to focus his research on plants illustrated on Maya ceramics, culminating in the creation of a botanical resource database of the plants depicted in Classic Maya art, with the goal of rediscovering unknown or forgotten plants that were important to the ancient Maya. The initial results of this research have now been published.

As we have discussed, the International Narcotics Control Board — a United Nations monitoring body that oversees the implementation of the UN drug control conventions — has called for the governments of Bolivia and Peru to abolish all uses of the coca leaf, including coca leaf chewing. In its 2007 annual report, the INCB asked Bolivia and Peru to make possessing and using coca leaf criminal offenses — a move that would make criminals of millions of people in the Andes and Amazon.

Peyote songs are the prayer music and ceremonial heart of the Native American Church. The songs have traditionally been sung, accompanied by the gourd rattle and water drum, in the various languages and musical styles of the indigenous peoples from which the church drew its membership. At the same time, the pan-Indian nature of the church made it a powerful vehicle for the diffusion of musical styles and content. Early studies of peyote songs, dating from the 1940s, found Navajo peyote singers using the Ute musical style, and recognizably the same peyote song among the Tarahumara, Navajo, and Cheyenne.

Jerónimo M. M. is a professor of interactive TV and mobile applications, as well as a consultant on Internet video, online communities, and user experience for such clients as MTV, Tele5, The Movie Channel, and Telefonica. For the past seven years he has been working on a documentary film project entitled The Ayahuasca Conversation.