Explore Articles Filed Under: Indigenous Culture

Amazonian mestizos believe that it is possible to lose one’s soul, or part of one’s soul, through more or less natural processes; indeed, soul loss through susto, fright, is a relatively common childhood condition. The sickness category of susto is undoubtedly derived from traditional Hispanic medicine; indigenous Amazonian shamanic traditions of soul loss appear to be too distant geographically and conceptually — for example, among the Wakuénai — to have significantly contributed to the idea. Mestizo shamans also frequently use the term manchari for the same condition, presumably from the Quechua manchay, be afraid.

The air, especially at night, is full of souls — souls of the dead, souls of departed and powerful shamans, and what my teacher doña María Tuesta called almas olvidadas, forgotten souls, the wandering spirits of those who were neglected and abused while alive. The wandering and sorrowful soul of a dead person may appear as a being called a tunchi. An evil spirit of the dead, driven by malignancy rather than sorrow, is called a maligno or an alma mala, an evil soul.

Face and body painting have been important parts of Amazonian culture for centuries. Face painting in particular has played an important part in hunting, warfare, and courtship. Traditional designs could designate status and identity. A man’s facial paint can give him courage and power; a woman’s facial paint gives her … well, sex appeal. Face painting also played important social roles; among the Shipibo, for example, painting a man’s face in traditional designs was a job performed only by women.

The bufeo colorado, pink dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), is considered a powerful shaman, which casts spells when it surfaces, perhaps because its blowhole makes blowing and whistling sounds similar to those made by a shaman. Much dolphin behavior supports belief in their intelligence. They are curious, and they will swim near boats and approach swimmers in the water. They will chase a school of fish, allowing fishermen to go upstream and set their nets; the dolphins will then remain on the outside of the nets, easily capturing any fish that escape — a curiously symbiotic relation between humans and dolphins.

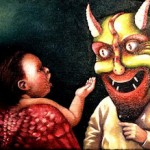

The chullachaqui is a demon of the jungle, known to almost everyone in the Amazon, frightening and pathetic. He is characterized by having one or both feet deformed — either both turned backwards, or one shaped like that of an animal, such as a deer or jaguar; the name is Quechua, meaning uneven feet. The deformed foot is emblematic of his nature: turned backwards, it leaves false tracks; but it cannot be disguised, revealing his identity.

Mestizos in the Upper Amazon have a variety of beliefs about the other-than-human persons who inhabit the hidden realms deep in the jungle and under the water. These beings are often conceived as inhabiting the three realms of air, earth, and water; all of them are dangerous. They are different from the madres or genios, the spirits of plants and animals with whom the shaman interacts, although shamans often seek to enter into right relationship with these beings as well; rather, ordinary people may, to their sorrow, unintentionally and unexpectedly encounter these more-or-less corporeal other-than-human persons.

Early anthropologist Martin Gusinde reports the following performance by a shaman in Tierra del Fuego: “He put a few pebbles in the palm of his hand, concentrated on them, and suddenly the pebbles vanished.” Can anyone with even a rudimentary knowledge of sleight-of-hand believe this wasn’t a conjuring trick?

We reported earlier about efforts to maintain peyote populations in northern Mexico, in the sacred peyote grounds of the Huichol. A Reuters news service story yesterday by Jeff Franks tells a less hopeful story about the peyote harvest north of the border.

Cultural critics Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearson point out that music can be understood either as possessing or producing meanings, or as producing effects which cannot be explained in terms of meaning — that “music can affect us in ways that are not dependent on understanding something, or manipulating verbal concepts, or being able to represent accurately those experiences through language.” Music thus has a metaphysical dimension; where music affects the body, the distinction between outside — where the music comes from — and inside — where the music is felt — is radically called into question.

In yesterday’s National Catholic Reporter, columnist John Allen tells the following story. In the summer of 2002, Pope John Paul II was in Mexico City to canonize Juan Diego, the Aztec visionary devotee of Our Lady of Guadalupe. On the day after the canonization mass, John Paul also beatified two indigenous martyrs.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa