Explore Articles Filed Under: Indigenous Culture

The wilderness is a teacher, and it teaches, often implacably, the natural consequences of our actions. It’s simple: if I haven’t set up a shelter and it rains, then I get wet. But the lessons of the wilderness go much deeper than that. The wilderness teaches, in Kierkegaard’s words, how to exist humanly — remembering what is important, in right relationship, in touch with meaning in the world. Here are ten such lessons that the wilderness has taught me.

At a meeting of the Native American Church, after a long night of singing and praying, the participants are served a sacred breakfast of small amounts of water, parched corn, and pemmican as the close of the ceremony. This is then followed by an informal breakfast where people eat, stretch their cramped legs, chat, and tell funny stories, often having to do with peyote and peyote ceremonies. James Howard, a professor at the University of North Dakota, calls these stories peyote jokes.

Over a period of twenty months, fourteen shamans were murdered in the district of Balsapuerto, a small river port in Alto Amazonas province. Seven of the victims had been shot, stabbed, or hacked to death; seven others had been reported missing, but their bodies had not been found, presumably because they had been tossed into rivers to be eaten by piranhas. All those killed — as well as almost all the members of the communities from which they came — were members of the Shawi ethnic group. How could such a thing have happened?

The ayahuasca drink is made from the stem of the ayahuasca vine. Sometimes, but rarely, the drink is made from the vine alone; almost invariably other plants are added. It is in fact this companion plant that contains the potent hallucinogen dimethyltryptamine; the vine contains MAO inhibitors. How in the world did indigenous peoples in the Upper Amazon come up with the idea of combining DMT with an MAO inhibitor? And when and where did they first do it?

Fusion is the hot word among Peruvian chefs. Pedro Miguel Schiaffino was one of the founders of what is now generally called Amazon fusion, which incorporates jungle ingredients into gourmet dishes. Back in May, the first Festival Gastronómico de la Amazonía peruana was held for five days at the Hotel Meliá in Lima. I missed it. I had intended to bring some genuine Amazonian boiled monkey soup, but, as it turns out, it is likely the festival would not have been interested. When people in Lima speak of Amazonian gastronomy, they do not mean what indigenous people in the Amazon actually eat.

In 1975 Kenneth Good traveled to Venezuela to study the Yanomamö. After he had lived in the village for about two years, he found himself under increasing pressure to become betrothed. “What the hell,” he thought, “what would be so wrong in saying yes?” So he became betrothed to Yarima, who at that time was around nine years old. Then something unexpected happened. Good began to fall in love with Yarima. He consummated their marriage when she was about fourteen, and he was almost forty. Five years later, after having lived with the Yanomamö for more than twelve years, Good brought his now-pregnant wife back to the United States. Things did not work out as he had expected.

Do warfare and killing among Amazonian peoples have an evolutionary function? Anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon claims that the culture of the Yanomamö of Brazil exemplifies a key principle of sociobiology — that males who had murdered during intervillage warfare had more than twice as many wives and three times as many children as men who had not. In other words, he claims that violence is evolutionary adaptive behavior. Now a new study of violence and reproductive success, this time among the Waorani of Ecuador, has come to a different conclusion.

Type 2 diabetes has reached epidemic proportions among Native Americans. Complications from diabetes are major causes of death and health problems in almost every Native American community. In the film The Gift of Diabetes, Ojibway filmmaker Brion Whitford uses his own diabetes as a metaphor for his “self-loathing and alienation from my people.” His disease is the physical form of a spiritual condition, a sickness of the soul; and his quest for understanding takes him on a journey back to his own traditions.

The plant Salvia divinorum has a long and continuing tradition of use by Mazatec shamans, who drink it, sometimes followed by a drink of tequila, to induce visionary states during healing sessions. Popular use of Salvia, especially among young people, has been increasing — along with calls for its criminalization. Some medical researchers argue that scheduling the drug should wait until evidence about its effects and toxicity becomes clear. A recent article in Scientific American addresses the issues.

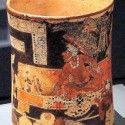

In 2001, a graduate student named Charles Zidar heard a lecture on the polychrome ceramics of the Classic Maya. The lecturer mentioned, in passing, that the botanical motifs with which many of these ceramics were decorated remained unidentified. This remark inspired Zidar, a natural historian and archaeologist, to focus his research on plants illustrated on Maya ceramics, culminating in the creation of a botanical resource database of the plants depicted in Classic Maya art, with the goal of rediscovering unknown or forgotten plants that were important to the ancient Maya. The initial results of this research have now been published.