Explore Articles Filed Under: Ayahuasca

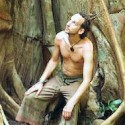

Daniel Mirante is a young — thirty years old, which is young to me — visionary artist, author, and researcher fascinated with deep ecology, shamanic traditions, ancient mythology, and the creative process. In 2000, he founded the well-known Lila website — the word lila means something like cosmic play in Sanskrit — as a creative collective and resource for people exploring what Delvin Solkinson of the Elfintome Arts Collective has called medicine culture — shamanic forms of creativity and healing, including plant-based entheogenic practices.

A number of artists have attempted to render the striking visual experiences that occur after ingesting ayahuasca or DMT. In the Upper Amazon, there are both indigenous artists, whose traditional work consists largely of abstract patterns, such as those found on the now well-known pottery, clothing, and other household goods of the Shipibo; and visionary artists, mostly mestizo, whose work is characterized by detailed representations of spirits, trees, animals, objects, and participants in ayahuasca healing ceremonies.

A virote was originally a crossbow bolt, brought to South America by the conquistadores. The Spanish term was then applied to the darts shot by the Indians with a blowgun. These darts were made primarily from two sources — from the spines of any of the spiny Bactris or Astrocaryum palms or from any of several Euterpe palms, whose very hard wood is used to make both bows and arrows. My jungle survival instructor, Gerineldo Moises Chavez, could whittle a usable dart from the wood of a Euterpe palm with his machete in less than a minute.

The shaman can see things that people who are not shamans cannot. The shaman may be able to find lost objects, know where game is plentiful, discern who has cast a curse, diagnose the location or cause of an illness. Many scholars, influenced by the work of Mircea Eliade, maintain that the characteristic activity of shamanism is soul flight — celestial ascent, ecstasy, out-of-body journeys to the spirit realm, almost always vertically, upwards, toward the sky. And it is true that, among some shamanic traditions, out-of-body flight is the way that shamans acquire the information that is their stock in trade. They travel through the air and go look. Shamanism in the Upper Amazon is, I think, different.

There is an often unspoken hierarchy among mestizo shamans. There is, first, a relatively informal ranking based on length of practice, the number and length of dietas, the number and types of plants that have been mastered, and the number and quality of icaros in their repertoire. Icaros become increasingly prestigious as they incorporate words from indigenous languages, unknown archaic tongues, and the languages of animals and birds; the more obscure the language, the more power it contains — and the more difficult it is to copy.

The attack took place at the tourist lodge, at night, when doña María was sleeping. She tried to get out of bed to urinate, but, when she got up, she fell to the floor, partially paralyzed, unable to move. She cried for help. One worker came, but he was not strong enough to move her. Eventually, with the help of the gringo owner, she was lifted back onto the bed. “She was just like dead weight,” the owner later told me. “It was all I could do to get her up to her bed myself.”

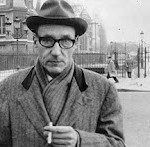

American novelist William S. Burroughs ended his first book, originally published as Junky under the pseudonym William Lee, with a brief meditation on yagé. “I read about a drug called yage, used by Indians in the headwaters of the Amazon,” he writes. “I decided to go down to Colombia and score for yage. . . . I am ready to move on south and look for the uncut kick that opens out instead of narrowing down like junk.” The last sentence in the book reads, “Yage may be the final fix.”

There are relatively few women shamans in the Amazon, and certainly few among the mestizos. On the other hand, my teacher doña María Tuesta said that she had encountered very little prejudice because she was an ayahuasquera. There were some shamans who have said that she should not be a healer, but — in her typical way — she said that those were all stupid people with no shamanic power anyway. Still, her vocation is rare.

On February 3, the Los Angeles Times Magazine published an article on a self-professed ayahuasquero named Lobo Siete Truenos, or Wolf Seven Thunders, and the growing role of ayahuasca in what the article calls the “nouveau wealth” of suburban California.

In the Upper Amazon, the restricted diet — self-denial of food and sex — is a necessary precondition for creating a relationship with the plants. What the plants give in return is their willingness to help the shaman; their icaro, their song; and phlegm. Planting and nurturing the magical phlegm is an indispensable goal of the apprenticeship training; the phlegm is the physical embodiment of fuerza, the shaman’s power.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa