Explore Articles Filed Under: The Amazon

We have spoken, briefly, about Takiwasi, the Center for the Treatment of Drug and Alcohol Addiction and the Research of Traditional Medicines, located in Tarapoto, and its techniques for healing addiction using ayahuasca and other traditional Amazonian medicines. Takiwasi — the name means House that Sings — was founded and continues to be directed by French physician Jacques Mabit. Whatever you may think of his methods or his claimed results, there is no doubt that Mabit is a fascinating guy.

Why is it called the Amazon River? The first occurrence of the Greek word Amazon is in the Iliad, two times, both with the same epithet: ‘Αμαζονας αντιανειρας, Amazons who fight like men. In the centuries following, there were many additional references to armed and mounted women, fierce warriors, fighting the Greeks. Indeed, the αμαζονομαχιες, the battle between Greeks and Amazons, became a favorite theme with vase painters and sculptors of friezes.

Andy Graham at HoboTraveler has pointed to an article in the Pucallpa newspaper Diario Ahora, dated June 5, 2008, with the headline Indígenas de Yurúa señalan que no existe población no contactada, Indigenous People of Yurúa Say There Are No Uncontacted Populations.

Indigenous people all over the world are already embedded in global modernity, whether anyone likes it or not. There is no turning back, no way to disengage from the modern world, nowhere for indigenous peoples to retreat. And I think it is fair to say that indigenous people are, generally, worse off in many ways since this change than they were before. Still, there are aspects of modernity — modern dentistry, for example — which could be of benefit to indigenous people if they had access to them.

There is an ambiguity inherent in shamanic practice, where the dangerous work of healing and sorcery intersect. Because shamans possess spirit darts, and with them the power to kill, the boundary between sorcerer and shaman is indistinct. Such shamanism, says social anthropologist Carlos Fausto, “thrives on ambivalence.” In the Upper Amazon, life and death are inextricably intertwined, and the cosmos is conceptualized in terms of predator-prey relationships.

Among Amazonian mestizos, the world is often viewed in terms of male and female, macho and hembra. Not only animals but also plants — even inanimate objects — appear in both male and female forms; rain, for example, can be male or female, depending on the force with which it falls; if a plant species has two varieties, one with thorns, the one with thorns is considered male.

In the Amazon, plants and animals are ascribed the status of persons, who may differ corporeally from human persons but, like them, possess intentionality and agency. Indeed, other-than-human persons are believed to see themselves in human form, and thus to be self-aware of their own personhood. Among the Ashéninka, for example, a white-lipped peccary is held to perceive its own herd as a foraging human tribe, its wallow as a human village, and the wild root it eats as cultivated manioc.

In the Upper Amazon, people believe that there are sorcerers, and that much of human suffering — sickness, death, misfortune, bad luck and trouble — is caused by sorcerers, either from the sorcerer’s own malevolence, or on behalf of an embittered and resentful client. There is little that the ordinary state apparatus can do about sorcery. Alejandro Tsakimp, a Shuar shaman, puts the thought this way: “They killed my father with witchcraft and not with a bullet…. With killings like this, through witchcraft, there aren’t any witnesses. I can talk about all this, I can go to lawyers, but nobody will believe me.”

Mestizo shamanism is found in an arc from southern Colombia and Ecuador to northern Bolivia, through the present-day Peruvian departamentos of Loreto and Ucayali, westward along the Río Marañon, and spilling over eastward into western Brazil. This distribution is the result of historical factors, one of which was the great Rubber Boom — a period of about thirty-five years, approximately from 1880 to 1914, which transformed Amazonian culture in ways both profound and irremediable.

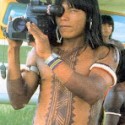

Photographer Vance Gellert has come back from South America with a series of striking photographs of healers and healing, currently on display at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, in an exhibit entitled Smoke and Mirrors: A Journey to Healing Knowledge. Gellert used medium- and large-format film cameras to bring out details and vibrant colors, to evoke a spirit of place; photography, he says, captures images infused with layers of meaning and nuance that give the recorded facts a human and emotional connection.

Discussing the article:

Hallucinogens in Africa