Introduction

|

| Carl Jung |

In December 1913, Jung first experienced what he was later to call active imagination. However, he did not talk about these experiences until twelve years later, when, in May and June 1925, he “spoke for the first time of his inner development” (Jaffé, 1962/1963, p. vii) at two sessions of a series of weekly seminars he was giving in Zurich. The contents of these lectures were not published until 1989 (Jung, 1989); but a partial account of these experiences was given in 1962 by Aniela Jaffé in Jung’s Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Jung, C., 1962/1963, pp. 170-199), which she largely wrote. This account is the foundation myth, the charter, for active imagination.

In 1913, according to this account, Jung, profoundly distressed at his break with Freud, began to experiment with different ways to enter into his own imaginings. As James Hillman describes it, “When there was nothing else to hold to, Jung turned to the personified images of interior vision. He entered into an interior drama, took himself into an imaginative fiction and then, perhaps, began his healing — even if it has been called his breakdown” (Hillman, 1983b, p. 54).

In this imaginal world, Jung began to confront and question the figures who appeared to him; and, to Jung’s surprise, those imaginal persons replied to him in turn. “Near the steep slope of a rock,” Jung says, “I caught sight of two figures, an old man with a white beard and a beautiful young girl. I summoned up my courage and approached them as though they were real people, and listened attentively to what they told me” (Jung, 1962/1997, p. 28). And again: “I held conversations with him, and he said things which I had not consciously thought. For I observed clearly that it was he who spoke, not I” (p. 30). One of these imaginal people, a wise pagan whom Jung named Philemon, “seemed to me quite real, as if he were a living personality.” Philemon spoke to Jung as follows: “He said I treated thoughts as if I generated them myself, but in his view thoughts were like animals in the forest, or people in a room, or birds in the air.” It was this imaginal Philemon who taught Jung the reality of the psyche — “that there is something in me which can say things that I do not know and do not intend” (p. 30).

The nature of active imagination

The idea of active imagination derives from Jung’s belief that the unconscious has an independent symbol-producing capacity. In traditional Jungian thought, active imagination is a special type of fantasy involving the participation of the ego and with the goal of a connection to internal objective reality. Thus viewed, active imagination is a channel for messages from the unconscious (Samuels, 1985, p. 12; see generally Powell, 1998; Singer, 1994, pp. 272-315). “Properly understood and pursued, the imagination is perhaps our most reliable way of bringing the world of the unconscious into some degree of consciousness and our best means of corresponding with the graces offered us in the life of the spirit” (Ulanov & Ulanov, 1999, p. 3).

In its simplest form, active imagination is an imaginal dialogue — a conversation between me, the ego, and something else that is not-me, the unconscious, of which I am not normally aware (Cwik, 1995, p. 138). Most important, the dialogue with the contents of the unconscious is with a person — “exactly as if,” says Jung, “a dialogue were taking place between two human beings with equal rights” (Jung, 1958/1997, ¶ 186, p. 58). Thus Jung states that “the essential thing is to differentiate oneself from these contents by personifying them, and at the same time to bring them into relationship with consciousness” (Jung, C., 1962/1963,p. 187). Personifying, says James Hillman, “allows the multiplicity of psychic phenomena to be experienced as voices, faces, and names. Psychic phenomena can then be perceived with precision and particularity, rather than generalized in the manner of faculty psychology as feelings, ideas, sensations, and the like” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 62).

The technique of active imagination

A note on terminology

The concept of active imagination originally embraced every form of interaction with a symbol — dramatic, dialectic, visual, acoustic, or in the form of painting, drawing, sculpting, writing, even dance (e.g., Jung, 1947a/1997, p. 159). With the passage of time, the term has come to be more restricted, and generally now refers to imaginal pictures and conversations (Kast, 1993, p. 166), although the original usage survives in many form of art therapy, sandplay, and other forms of expressive therapy (e.g., Powell, 1998).

In Jung’s work there are two forms or phases of active imagination, which we will call inspection (Betrachtung) and confrontation (Auseinandersetzung). The two words are important. In inspection, one focuses on a visual image — it could be from a dream, vision, fantasy, even a photograph — until it becomes alive. As Jung stated in a 1932 lecture on visions, the verb betrachten means both inspect, examine, scrutinize and make pregnant. “And if it is pregnant,” Jung says, “then something is due to come out of it: it is alive, it produces, it multiplies. That is the case with any fantasy image; one concentrates upon it, and then finds that one has great difficulty in keeping the thing quiet, it gets restless, it shifts, something is added, or it multiplies itself; one fills it with a living power and it becomes pregnant” (quoted in Chodorow, 1997, p. 7).

In confrontation, one approaches this now living image, this imaginal person, and questions it: Who are you? Why are you here? What are you doing? What is your meaning to me? The word Auseinandersetzung captures this: it means “placing over against” and thus discussion, argument, altercation, conflict, showdown. In the English translation of Jung’s writings, unfortunately, Auseinandersetzung is often translated as “coming to terms,” which fails to convey, in my opinion, the face-to-face quality of the imaginal encounter.

Inspection

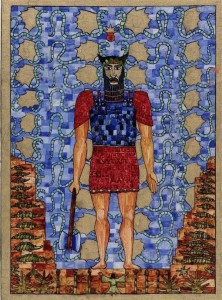

|

| Car Jung, painting from The Red Book (2009) |

The first stage, inspection, requires the elimination of critical attention to produce “a vacuum in consciousness” (Jung, 1958/1997, ¶ 155, p. 50); it involves a suspension of the rational, critical faculties in order to give free rein to imagination, to “encourage the emergence of any fantasies that are lying in readiness” ( Jung, 1958/1997, ¶ 155, p. 50). Critical attention must be eliminated; there must be an expectation that an inner image will appear (Jung, 1958/1997, ¶ 170, p. 54). This is not at all easy. “It is almost insuperably difficult,” Jung says, “to forget, even for a moment, that all this is only fantasy, a figment of the imagination that must strike one as altogether arbitrary and artificial” (Jung, 1928/1997, ¶ 351, pp. 64-65).

But such suspension of disbelief is fundamental to the process. As the Ulanovs put it, “Letting our imagination be is both not so simple as it sounds and much simpler than we would expect. What we are after is noninterference. We must refuse to be hasty. We must put aside perfectionist or utopian pictures. There is nowhere we must get to; there are no prescribed images that must appear… We allow whatever will come to us and open ourselves to it, whether it be in sight, sound, touch, taste, or smell” (Ulanov & Ulanov, 1999, p. 21).

When one thus concentrates on a mental picture, says Jung, “it begins to stir, the image becomes enriched by details, it moves and develops” (Jung, 1935/1997,¶ 398, p. 145). As Jung describes the process, “[y]ou choose an image and concentrate on it simply by catching hold of it and looking at it… You then fix this image in the mind by concentrating your attention. Usually it will alter, as the mere fact of contemplating it animates it… A chain of fantasy ideas develops and gradually takes on a dramatic character: the passive process becomes an action. At first it consists of projected figures, and these images are observed like scenes in the theater. In other words, you dream with open eyes” (Jung, 1955/1997, ¶ 706, p. 167; emphasis added; see also Jung, 1947/1997b, p. 164).

Confrontation

In the second stage, confrontation, the ego enters actively into the experience. “[T]he fantasy, to be completely experienced, demands not just perception and passivity, but active participation” (Jung, 1928/1997, ¶ 350, p. 64). Indeed, the now living image demands engagement. “The piece that is being played does not want merely to be watched impartially, it wants to compel participation. If the observer understands that his own drama is being performed on this inner stage, he cannot remain indifferent to the plot and its dénouement. He therefore feels compelled . . . to take part in the play” (Jung, 1955/1997, ¶ 706, p. 167).

In other words, the imaginal persons must now be approached, confronted, questioned, engaged. “[S]tep into the picture yourself,” Jung says, “and if it is a speaking figure at all then say what you have to say to that figure and listen to what he or she has to say” (Jung, 1947/1997b, p. 164); “[m]ake use of the opportunity and start some dialogue” (p. 165). A natural response to such an encounter would be to follow one’s surprise and put a question or two, Jung says. Treat the image as a person — above all, as something that really exists. “You must talk to this person to see what she is about and learn what her thoughts and character are” (p. 165).

And such participation is not only intellectual. One patient imagined seeing his fiancée run out onto the ice of a frozen river. The ice cracked, a dark fissure appeared, and she jumped into the crack, while he stood by in sorrow (Jung, 1928/1997, ¶ 343, p. 62). In real life, Jung says, the patient would never remain an idle spectator while his fiancée tried to drown herself; he would leap up and stop her. To behave in imagination as one would in reality is the way to take the imaginal seriously (Jung, 1928/1997, ¶ 350, p. 64). Humbert (1971, p. 104, quoted in Cwik, 1995, p. 152) tells the following story:

A woman whom Jung was analyzing reported the following active imagination: “I am by the edge of the sea and I see a lion coming, but it turns into a boat.” He replied: “That is not true. If you are by the edge of the sea and you see a lion coming you feel afraid, you tremble, you wonder what to do. There is no question of it turning immediately into a boat.”

Application

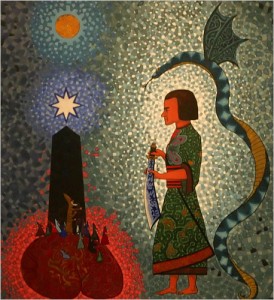

|

| Carl Jung, painting from The Red Book (2009) |

Contemporary traditional Jungian analysts (e.g., Weaver, 1973; Hannah, 1981; Dallett, 1982; Von Franz, 1983; Johnson, 1986; Cwik, 1995; see Chodorow, 1997, p. 11) have expanded, modified, and supplemented this two-stage process in various ways. Interestingly, there has been a tendency to add an explicit step at the end. Marie-Louise von Franz says that an essential component of this end stage is “to apply whatever is said, ordered, or asked for in active imagination to ordinary life” (1983, p. 133). Jane Dallett (1982, p. 177) calls the final stage living it.

What is being encouraged here is that the learnings and insights from the process be integrated into life and consciousness (Cwik, 1995, p. 154). And this must be something physical; von Franz talks about allowing the body to play. Robert Johnson speaks of incarnating active imagination — giving it a physical quality “to bring it off the abstract rarefied level and connect it to your physical earthbound life” (1986, p. 196). This requires a physical act — a ritual — that will affirm the message received in active imagination (p. 97). At its best, Johnson says, “ritual is a series of physical acts that expresses in condensed form one’s relationship to the inner world of the unconscious” (p. 103). But anything that “keeps and honors the process” — making an apology, putting flowers on a grave — may be enough (Cwik, 1995, p. 154).

The imaginal world

The active imagination enters its own landscape, the imaginal world, peopled with guides and spirits, demons and tigers. “It is crucial to understand that the imaginal world has a reality of its own, within the four walls of its own realm” (Rowan, 1993, p. 63). In this imaginal world, Hillman says, “[w]e have to engage with persons whose autonomy may radically alter, even dominate our thoughts and feelings, neither ordering these persons about nor yielding to them full sway” (Hillman, 1983b, p. 55). Mary Watkins says that one creates for oneself a home in the imaginal. “This home, the various imaginal egos, is created from the very material of the imaginal — images. With its creation the non-material side of metaphor becomes more apparent, more inhabited, more clearly a part of our wanderings” (Watkins, 1976, p. 124).

This world has, too, its own language. “The imaginal resists being known except in its own terms. Image requires image. Image evokes image. Systems of understanding arise, themselves symbolic. It is as if one can say what the imaginal is like, but cannot utter what it is” (Watkins, 1976, p. 99; emphasis in original). This world is what Corbin calls the mundus imaginalis, “a very precise order of reality, which corresponds to a precise mode of perception” (Corbin, 1972/2000, 71). As Rowan puts it, the difference between the imaginary and the imaginal world is that “the imaginal world is a world where real things happen, and one of the things which happens is ‘the self open to others’” (Rowan, 1993, p. 54). In the imaginal world there is a space in one’s life where the great archetypal themes can live themselves out (Johnson, 1986, p. 157).

The ontology of imagination

Immediately we face the question of the nature and ontological status of these encountered persons: are they dissociated material (Singer, 1994, p. 288)? primordial images (Casey, 2000, pp. 214-215)? subpersonalities (Cwik, 1995, p. 141)? angels (see Chittick, 1994, pp. 83-95)? shamanic spirits (Noel, 1997, pp. 209-211)? gods (Hillman, 1975, p. 35)?

However described, what is important about these imaginal people is that they are autonomous and real. Their autonomy is a matter of experience. “The images,” Jung says, “have a life of their own, and the symbolic events develop according to their own logic” (Jung, 1935/1997, ¶ 397, p. 145); “[i]t is exactly as if a dialogue were taking place between two humans with equal rights” (Jung, 1958/1997, ¶ 186, p. 58). And Hillman adds, “When an image is realized — fully imagined as a living being other than myself — then it becomes a psychopompos, a guide with a soul having its own inherent limitation and necessity” (Hillman, 1983b, p. 62). When we actively confront these imaginal persons, respond to them with our own objections, awe, and arguments, then, as the Ulanovs put it, “we may come to the breath-stopping realization of just how independent of our conscious control such images are. They have a life of their own. They push at us. They talk back” (Ulanov & Ulanov, 1999, p. 41). Imaginal persons are “as they present themselves, . . . valid psychological subjects with wills and feelings like ours but not reducible to ours” (Hillman, 1975, p. 2; emphasis in original).

Their ontological status is more problematic. Jung insists that these imaginal people are — in some sense — real. “You have the idea that you have just made it up, that it is merely your own invention. But you must overcome that doubt, because it is not true” (Jung, 1935/1997, ¶ 398, p. 145).

There are two possible approaches to this question. Jung takes one: he insists on equal ontological rights for the unconscious. “Something works behind the veil of fantastic images,” he says, “whether we give this something a good name or a bad. It is something real, and for this reason its manifestations must be taken seriously” (¶ 353, p. 65). The two opposing realities, the world of the conscious and the world of the unconscious, “do not struggle for supremacy, but each makes the other relative” (¶ 354, p. 65). When the patient, in imagination, leaps up to rescue his fiancée who is, in imagination, leaping into a dark fissure in the ice, “he is assigning absolute reality value to the unconscious,” asserting the “validity of the irrational standpoint of the unconscious” (¶ 350, p. 64). Both realities are “psychic semblances painted on an inscrutably dark back-cloth. To the critical intelligence, nothing is left of absolute reality” (¶ 354, p. 65; emphasis in original).

James Hillman takes the other approach. He does not hypostasize the imaginary so much as he dereifies reality. He calls this soul-making. “Soul-making,” he says, “can be most succinctly defined as the individuation of imaginal reality” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 36). More specifically, the act of soul-making is imagining, the crafting of images (Hillman, 1983a, p. 36).

Soul-making is also described as imaging, that is, seeing or hearing by means of an imagining which sees through an event to its image. Imaging means releasing events from their literal understanding into a mythical appreciation. Soul-making, in this sense, is equated with de-literalizing — that psychological attitude which suspiciously disallows the naïve and given level of events in order to search out their shadowy, metaphorical significances for soul (Hillman, 1983a, p. 36).

The human adventure, he says, “is a wandering through the vale of the world for the sake of making soul” (Hillman, 1975, p. xv). “Soul is imagination,” he says, “a cavernous treasury . . . a confusion and richness, both . . . The cooking vessel of the soul takes in everything, everything can become soul; and by taking into its imagination any and all events, psychic space grows” (Hillman, 1990, pp. 122-123; emphasis in original). And soul is “the imaginative possibility in our natures, the experiencing through reflective speculation, dream, image, and fantasy — that mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical” (Hillman, 1975, p. xvi; emphasis in original). “The question of soul-making is ‘what does this event, this thing, this moment move in my soul?” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 37). Where Jung makes the imaginal real, Hillman makes reality imaginal.

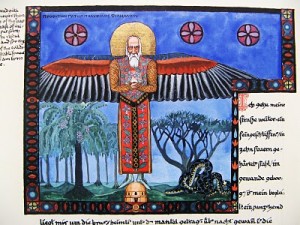

|

| Carl Jung, painting from The Red Book (2009) |

Hillman calls this seeing through — the ability of the imagination’s eye to see through the literal to the metaphorical (Hillman, 1975, p. 136). Re-visioning is deliteralizing or metaphorizing reality. The purpose of analysis is not to make the unconscious conscious, or to make id into ego, or to make ego into self; the purpose is to make the literal metaphorical, to make the real imaginal. The objective is to enable the realization that reality is imagination — that what appears most real is in fact an image with potentially profound metaphorical implications (Adams, 1997, pp. 104-105). Thus, says Hillman, soul is “the imaginative possibility in our natures . . . the mode which recognizes all realities as primarily symbolic or metaphorical,” (Hillman, 1975, p. xvi). “By means of the archetypal image, natural phenomena present faces that speak to the imagining soul rather than only conceal hidden laws and probabilities and manifest their objectification” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 19).

Indeed, for Hillman, consistent with this view, there are no archetypes as such; there are only images — or, as we have seen, phenomena in the world — that may be archetypal (Adams, 1997, p. 103). Any image can be considered archetypal; the word archetypal points to a value. Any image can gain this archetypal sense according to the value it reveals: the term archetypal, Hillman says, “refers to a move one makes rather than a thing that is” (Hillman, 1977, pp. 82-83, quoted in Hillman, 1983a, pp. 21-22). This use of the term is clearly related to the notion of soul-making. Emphasizing the valuative function of the adjective archetypal “restores to images their primordial place as that which gives psychic value to the world. Any image termed ‘archetypal’ is immediately valued as universal, trans-historical, basically profound, generative, highly intentional, and necessary” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 22).

The role of the ego

Jungian analysts have drawn a variety of conclusions about the relationship of these imaginal persons to me, to the ego. There is agreement that the nature of the ego-complex changes through engaging in active imagination; but how? For example, why are the contents of the unconscious personified? Jung says, “That is the technique for stripping them of their power” (Jung, C., 1962/1963,p. 187); Hillman says that is how one “encourages animistic engagement with the world” (Hillman, 1981, p. 52). In the first case, the imaginal persons are brought under the domination of the ego; in the second case, they spill over polycentrically into the world.

Traditional views

Traditional Jungian therapists tend to see active imagination in the service of centering, cohesion, convergence. Some see active imagination as a means to strengthen the ego. For example, imaginal persons may appear who directly support the ego, comfort and encourage, stand up for the rights of the ego when the ego faces external threat. Such an encouraging and ego-supportive imaginal figure, says Cwik, often disappears when it is no longer needed (Cwik, 1995, pp. 156, 159). Alternatively, personifying an unconscious content — naming it, giving it a face — can separate it from ego awareness, free the ego, disidentify from complexes, turn the ego-alien part of me into not-me (Cwik, 1995, p. 159). Others see active imagination as a means shifting the center from the ego to the self. As Cwik puts it, active imagination shifts the personality from ego-centeredness to a place much deeper within the psyche; a continued path of relativizing the ego — the individuation process — eventually leads to an ultimately unknowable center called the Self (Cwik, 1995, p. 161).

James Hillman

|

| James Hillman Photo by Cheryl Van Scoy |

What traditionalists have in common is the center. Other, more radical Jungians, such as James Hillman and Mary Watkins, see the value of active imagination in precisely the opposite way — as decentering the ego, dethroning it, leading to a personality which is more polytheistic, more polycentric, more democratic. Here the imaginal others remain autonomous, rather than being dissolved and integrated into the broader self.

James Hillman, of course, is an outspoken proponent of what he calls polytheistic psychology. “Of all the moves,” he writes, “none is so far-reaching in cultural implication as the attempt to recover the perspectives of polytheism” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 41). He equates the classical Jungian focus on the self to a species of monotheism. “The preference for self and monotheism,” he says, “strikes to the heart of a psychology which stresses the plurality of the archetypes” (Hillman, 1971/2000, p. 21). Instead, he says, “[t]he plurality of archetypal forms reflects the pagan level of things and what might be called a polytheistic psychology. It provides for many varieties of consciousness, styles of existence, and ways of soul-making” (Hillman, 1970/2000, p. 17). Hillman stands against “the strong ego, the suppressive integration of personality, and the unified independence of will” when they are at the expense of ambivalence, partial drives, complexes, images, vicissitudes. “A polytheistic model of the psyche,” he says, “seems logical and helpful when confronting the many voices and figments that pop up in any single patient, including myself. I can’t even imagine how we could ever have got on in therapy without a polytheistic background” (Hillman, 1971/2000, p. 49). And Hillman says, provocatively, “Multiple personality is humanity in its natural condition. In other cultures these multiple personalities have names, locations, energies, functions, voices, angel and animal forms, and even theoretical formulations as different kinds of soul” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 62; emphasis added).

Thus, Hillman considers the purpose of analysis to be the relativization of the ego by the imagination. “[T]herapy consists in giving support to the counter-ego forces, the personified figures who are ego-alien . . . [B]oth the theory of psychopathology and that of therapy assume a personality theory that is not ego-centered” (Hillman, 1983a, p. 62; emphasis added). The imagination relativizes — radically decenters — the ego, demonstrates that the ego too is an image, one among many, and not the most important one at that (Adams, 1997, p. 107). The imaginal, Hillman says, “not only relativizes ego consciousness but also relativizes the very idea of consciousness itself. It is then no longer clear when we are psychologically conscious and when unconscious. Even this fundamental discrimination, so important to the ego-complex, becomes ambiguous.” The ego, therefore, regards the imaginal as “elusive, capricious, vacillating.” But these words “describe a consciousness that is mediated to the unknown, conscious of its unconsciousness and, so, truly reflecting psychic reality” (Hillman, 1985, p. 141, quoted in Rowan, 1993, p. 60).

Mary Watkins

Mary Watkins

In contrast, Mary Watkins, who has written several classic texts on active imagination (1976, 2000b), has more recently come to view the decentering power of active imagination as essentially political action — a “depth psychology of liberation” (Watkins, 2000a, p. 222). In a new afterword to her 1986 Invisible Guests, claiming that what she says was implicit in the earlier text, Watkins asserts that the path of active imagination “aims at the allowing of the other to freely arise, to allow the other to exist autonomously from myself, to patiently wait for relation to occur in this open horizon, to move toward difference not with denial or rejection but with tolerance, curiosity, and a clear sense that it is in the encounter with otherness and multiplicity that deeper meanings can emerge” (2000b, p. 179). Watkins cites Buber (1970, pp. 5-6) for the Hasidic idea of holy converse. The term, she says, “describes equally well our relations with others, as it does our relations with ourselves, imaginal others, the beings of nature and earth, and that which we take to be divine.” Relationships with imaginal others that are dialogical are a subtext of holy converse more generally (Watkins, 2000b, pp. 179-180).

Thus, active imagination, she says, by keeping the ego from controlling psychic experience, means moving to a “place of witnessing which invites the other, the marginalized, to appear.” Having “a place to stand amidst multiplicity that is not fettered by efforts at control and domination [is] deeply in the spirit of a psychology of liberation” It is thus the repositioning of active imagination which has a healing effect, regardless of the content of the imagery (Watkins, 2000a, p. 222). Active imagination teaches political liberation.

REFERENCES

Adams, M. (1997). The archetypal school. In Young-Eisendrath, P., & Dawson, T. (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Jung (pp. 101-118). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Alquié, A. (1969). The philosophy of Surrealism. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Balakian, A. (1947). The literary origins of Surrealism. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Beyer, S. (1973). The cult of Tārā: Magic and ritual in Tibet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Beyer, S. (1977). Notes on the vision quest in early Mahāyāna. In Gomez, L., & Lancaster, L. (Eds.), Prajñāpāramitā and related systems: Studies in honor of Edward Conze (pp. 329-340). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Beyer, S. (2009). Singing to the plants: A guide to mestizo shamanism in the Upper Amazon. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Bosnak, R. (1988). A little course in dreams. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Breton, A. (1971a). Le manifeste du Surréalisme. In Waldberg, P. (Ed.), Surrealism. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Breton, A. (1971b). Le second manifeste du Surréalisme. In Balakian, A. (Ed.), Andre Breton: Magus of surrealism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Buber, M. (1970). The way of man. New York, NY: Citadel Press.

Cardeña, E., Lynn, S., & Krippner, S. (Eds.). (2000). Varieties of anomalous experience: Examining the scientific evidence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Casey, E. (2000). Imagining: A phenomenological study (2d ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Chittick, W. (1994). Imaginal worlds: Ibn al-‘Arabī and the problem of religious diversity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Chodorow, J. (1997). Introduction. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 1-20). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (1969). Creative imagination in the Sūfism of Ibn ‘Arabī (Mannheim, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (1977). Spiritual body and celestial earth (Pearson, N., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (2000). Mundus imaginalis: or the imaginary and the imaginal. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images (pp. 71-89). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1972)

Cwik, G. (1995). Active imagination: Synthesis in analysis. In Stein, M. (Ed.), Jungian analysis (2d ed., pp. 137-169). Chicago, IL: Open Court.

Dallett, J. (1982). Active imagination in practice. In Stein, M. (Ed.), Jungian analysis (pp. 173-191). LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

Eluard, P. (1932). Poetry’s evidence (Beckett, S., Trans.). This Quarter, 5(1).

Farthing, G. (1992). The psychology of consciousness. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Green, C., & McCreery, C. (1994). Lucid dreaming: The paradox of consciousness during sleep. London, UK: Routledge.

Hall, J., & Brylowski, A. (1991). Lucid dreaming and active imagination: Implications for Jungian therapy. Quadrant, 24(1), 35-43.

Harner, M. (1990). The way of the shaman (3d ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Hannah, B. (1981). Encounters with the soul: Active imagination as developed by C. G. Jung. Santa Monica, CA: Sigo Press.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Hillman, J. (1977). An inquiry into image. Spring, 62-88.

Hillman, J. (1983a). Archetypal psychology: A brief account. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1983b). Healing fiction. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1985). Anima. Dallas, TX: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1990). The essential James Hillman (Moore, T., Ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Hillman, J. (2000). Why “archetypal” psychology?. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images: The theoretical basis of archetypal psychology(pp. 11-18). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1970)

Hillman, J. (2000). Psychology: Monotheistic or polytheistic. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images: The theoretical bases of archetypal psychology (pp. 21-51). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1971)

Humbert, E. (1971). Active imagination: Theory and practice. Spring, 101-114.

Hunt, H. (1995). On the nature of consciousness: Cognitive, phenomenological, and transpersonal perspectives. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Jaffé, A. (1963). Introduction. In Jung, C. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jakobsen, M. (1999). Shamanism: Traditional and contemporary approaches to the mastery of spirits and healing. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Johnson, R. (1986). Inner work: Using dreams and active imagination for personal growth. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Jung, C. (1997). Confrontation with the unconscious. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 21-41). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jung, C. (1953-1977). Psychological types. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 6) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1921)

Jung, C. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jung, C. (1989). Analytical psychology: Notes of the seminar given in 1925. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. (1997). Mysterium Coniunctionis. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 166-174). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). Mysterium Coniunctionis. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 14) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1955)

Jung, C. (1997). On the nature of the psyche. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 158-162). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 8) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1947a)

Jung, C. (1997). The Tavistock lectures. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 143-153). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The symbolic life. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 18) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1935)

Jung, C. (1997). The technique of differentiation between the ego and the figures of the unconscious. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 61-72). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The relations between the ego and the unconscious, in Two essays on analytical psychology. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 7) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1928)

Jung, C. (1997). The transcendent function. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 42-60). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 8) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

Jung, C. (1997). Three letters to Mr. O. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 163-165). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1973). Letters (Vol. 1). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1947b)

Jung, C. G. (2009). The red book. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Kast, V. (1993). Imagination as the space of freedom: Dialogue between the ego and the unconscious (Hollo, A., Trans.). New York, NY: Fromm International.

LaBerge, S., & Gackenbach, J. (2000). Lucid dreaming. In Cardeña, E., Lynn, S., & Krippner, S. (Eds.), Varieties of anomalous experience: Examining the scientific evidence (pp. 151-182). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Noel, D. (1997). The soul of shamanism: Western fantasies, imaginal realities. New York, NY: Continuum.

Noll, R. (1985). Mental imagery cultivation as a cultural phenomenon: The role of visions in shamanism. Current Anthropology, 26, 443-451.

Powell, S. (1998). Active imagination: Dreaming with open eyes. In Allister, I., & Hauke, C. (Eds.), Contemporary Jungian analysis (pp. 142-155). London, UK: Routledge.

Ray, P. (1971). The Surrealist Movement in England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rowan, J. (1993). The transpersonal: Psychotherapy and counselling. London, UK: Routledge.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the post-Jungians. London, UK: Routledge.

Singer, J. (1994). Boundaries of the soul: The practice of Jung’s psychology (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Shafton, A. (1995). Dream reader: Contemporary approaches to the understanding of dreams. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Tart, C. (Ed.). (1969). Altered states of consciousness. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Ulanov, A., & Ulanov, B. (1999). The healing imagination: The meeting of psyche and soul. Einsiedlen, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag.

Von Franz, M. (1983). On active imagination. In Keyes, M. (Ed.), Inward journey: Art as therapy (pp. 125-133). LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

Watkins, M. (1976). Waking dreams. New York, NY: Harper Colophon.

Watkins, M. (2000a). Depth psychology and the liberation of being. In Brooke, R. (Ed.), Pathways into the Jungian world: Phenomenology and analytical psychology (pp. 217-233). London, UK: Routledge.

Watkins, M. (2000b). Invisible guests: The development of imaginal dialogues. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Weaver, R. (1973). The old wise woman: A study of active imagination. New York, NY: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Winkelman, M. (2000). Shamanism: The neural economy of consciousness and healing. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Previous Post: The Shamanic Art of Pablo Amaringo

- Next Post: Visualization Before Tantra

- More Articles Related to: Meditation, Research Studies

-

|

| Mary Watkins |

In contrast, Mary Watkins, who has written several classic texts on active imagination (1976, 2000b), has more recently come to view the decentering power of active imagination as essentially political action — a “depth psychology of liberation” (Watkins, 2000a, p. 222). In a new afterword to her 1986 Invisible Guests, claiming that what she says was implicit in the earlier text, Watkins asserts that the path of active imagination “aims at the allowing of the other to freely arise, to allow the other to exist autonomously from myself, to patiently wait for relation to occur in this open horizon, to move toward difference not with denial or rejection but with tolerance, curiosity, and a clear sense that it is in the encounter with otherness and multiplicity that deeper meanings can emerge” (2000b, p. 179). Watkins cites Buber (1970, pp. 5-6) for the Hasidic idea of holy converse. The term, she says, “describes equally well our relations with others, as it does our relations with ourselves, imaginal others, the beings of nature and earth, and that which we take to be divine.” Relationships with imaginal others that are dialogical are a subtext of holy converse more generally (Watkins, 2000b, pp. 179-180).

Thus, active imagination, she says, by keeping the ego from controlling psychic experience, means moving to a “place of witnessing which invites the other, the marginalized, to appear.” Having “a place to stand amidst multiplicity that is not fettered by efforts at control and domination [is] deeply in the spirit of a psychology of liberation” It is thus the repositioning of active imagination which has a healing effect, regardless of the content of the imagery (Watkins, 2000a, p. 222). Active imagination teaches political liberation.

REFERENCES

Adams, M. (1997). The archetypal school. In Young-Eisendrath, P., & Dawson, T. (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Jung (pp. 101-118). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Alquié, A. (1969). The philosophy of Surrealism. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Balakian, A. (1947). The literary origins of Surrealism. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Beyer, S. (1973). The cult of Tārā: Magic and ritual in Tibet. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Beyer, S. (1977). Notes on the vision quest in early Mahāyāna. In Gomez, L., & Lancaster, L. (Eds.), Prajñāpāramitā and related systems: Studies in honor of Edward Conze (pp. 329-340). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Beyer, S. (2009). Singing to the plants: A guide to mestizo shamanism in the Upper Amazon. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Bosnak, R. (1988). A little course in dreams. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Breton, A. (1971a). Le manifeste du Surréalisme. In Waldberg, P. (Ed.), Surrealism. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Breton, A. (1971b). Le second manifeste du Surréalisme. In Balakian, A. (Ed.), Andre Breton: Magus of surrealism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Buber, M. (1970). The way of man. New York, NY: Citadel Press.

Cardeña, E., Lynn, S., & Krippner, S. (Eds.). (2000). Varieties of anomalous experience: Examining the scientific evidence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Casey, E. (2000). Imagining: A phenomenological study (2d ed.). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Chittick, W. (1994). Imaginal worlds: Ibn al-‘Arabī and the problem of religious diversity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Chodorow, J. (1997). Introduction. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 1-20). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (1969). Creative imagination in the Sūfism of Ibn ‘Arabī (Mannheim, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (1977). Spiritual body and celestial earth (Pearson, N., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Corbin, H. (2000). Mundus imaginalis: or the imaginary and the imaginal. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images (pp. 71-89). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1972)

Cwik, G. (1995). Active imagination: Synthesis in analysis. In Stein, M. (Ed.), Jungian analysis (2d ed., pp. 137-169). Chicago, IL: Open Court.

Dallett, J. (1982). Active imagination in practice. In Stein, M. (Ed.), Jungian analysis (pp. 173-191). LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

Eluard, P. (1932). Poetry’s evidence (Beckett, S., Trans.). This Quarter, 5(1).

Farthing, G. (1992). The psychology of consciousness. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Green, C., & McCreery, C. (1994). Lucid dreaming: The paradox of consciousness during sleep. London, UK: Routledge.

Hall, J., & Brylowski, A. (1991). Lucid dreaming and active imagination: Implications for Jungian therapy. Quadrant, 24(1), 35-43.

Harner, M. (1990). The way of the shaman (3d ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Hannah, B. (1981). Encounters with the soul: Active imagination as developed by C. G. Jung. Santa Monica, CA: Sigo Press.

Hillman, J. (1975). Re-visioning psychology. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Hillman, J. (1977). An inquiry into image. Spring, 62-88.

Hillman, J. (1983a). Archetypal psychology: A brief account. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1983b). Healing fiction. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1985). Anima. Dallas, TX: Spring Publications.

Hillman, J. (1990). The essential James Hillman (Moore, T., Ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Hillman, J. (2000). Why “archetypal” psychology?. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images: The theoretical basis of archetypal psychology(pp. 11-18). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1970)

Hillman, J. (2000). Psychology: Monotheistic or polytheistic. In Sells, B. (Ed.), Working with images: The theoretical bases of archetypal psychology (pp. 21-51). Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. (Original work published 1971)

Humbert, E. (1971). Active imagination: Theory and practice. Spring, 101-114.

Hunt, H. (1995). On the nature of consciousness: Cognitive, phenomenological, and transpersonal perspectives. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Jaffé, A. (1963). Introduction. In Jung, C. Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jakobsen, M. (1999). Shamanism: Traditional and contemporary approaches to the mastery of spirits and healing. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Johnson, R. (1986). Inner work: Using dreams and active imagination for personal growth. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Jung, C. (1997). Confrontation with the unconscious. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 21-41). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jung, C. (1953-1977). Psychological types. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 6) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1921)

Jung, C. (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections (Winston, R., & Winston, C., Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1962)

Jung, C. (1989). Analytical psychology: Notes of the seminar given in 1925. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. (1997). Mysterium Coniunctionis. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 166-174). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). Mysterium Coniunctionis. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 14) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1955)

Jung, C. (1997). On the nature of the psyche. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 158-162). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 8) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1947a)

Jung, C. (1997). The Tavistock lectures. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 143-153). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The symbolic life. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 18) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1935)

Jung, C. (1997). The technique of differentiation between the ego and the figures of the unconscious. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 61-72). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The relations between the ego and the unconscious, in Two essays on analytical psychology. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 7) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1928)

Jung, C. (1997). The transcendent function. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 42-60). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1953-1977). The structure and dynamics of the psyche. In Read, H., Fordham, M., & Adler, G. (Eds.). Collected works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 8) (Hull, R., Trans.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1958)

Jung, C. (1997). Three letters to Mr. O. In Chodorow, J. (Ed.), Jung on active imagination (pp. 163-165). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Excerpt from Jung, C. (1973). Letters (Vol. 1). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1947b)

Jung, C. G. (2009). The red book. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Kast, V. (1993). Imagination as the space of freedom: Dialogue between the ego and the unconscious (Hollo, A., Trans.). New York, NY: Fromm International.

LaBerge, S., & Gackenbach, J. (2000). Lucid dreaming. In Cardeña, E., Lynn, S., & Krippner, S. (Eds.), Varieties of anomalous experience: Examining the scientific evidence (pp. 151-182). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Noel, D. (1997). The soul of shamanism: Western fantasies, imaginal realities. New York, NY: Continuum.

Noll, R. (1985). Mental imagery cultivation as a cultural phenomenon: The role of visions in shamanism. Current Anthropology, 26, 443-451.

Powell, S. (1998). Active imagination: Dreaming with open eyes. In Allister, I., & Hauke, C. (Eds.), Contemporary Jungian analysis (pp. 142-155). London, UK: Routledge.

Ray, P. (1971). The Surrealist Movement in England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rowan, J. (1993). The transpersonal: Psychotherapy and counselling. London, UK: Routledge.

Samuels, A. (1985). Jung and the post-Jungians. London, UK: Routledge.

Singer, J. (1994). Boundaries of the soul: The practice of Jung’s psychology (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Shafton, A. (1995). Dream reader: Contemporary approaches to the understanding of dreams. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Tart, C. (Ed.). (1969). Altered states of consciousness. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Ulanov, A., & Ulanov, B. (1999). The healing imagination: The meeting of psyche and soul. Einsiedlen, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag.

Von Franz, M. (1983). On active imagination. In Keyes, M. (Ed.), Inward journey: Art as therapy (pp. 125-133). LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

Watkins, M. (1976). Waking dreams. New York, NY: Harper Colophon.

Watkins, M. (2000a). Depth psychology and the liberation of being. In Brooke, R. (Ed.), Pathways into the Jungian world: Phenomenology and analytical psychology (pp. 217-233). London, UK: Routledge.

Watkins, M. (2000b). Invisible guests: The development of imaginal dialogues. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications.

Weaver, R. (1973). The old wise woman: A study of active imagination. New York, NY: G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Winkelman, M. (2000). Shamanism: The neural economy of consciousness and healing. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

- Previous Post: The Shamanic Art of Pablo Amaringo

- Next Post: Visualization Before Tantra

- More Articles Related to: Meditation, Research Studies

Thankyou for this article.So comprehensive. My own experience of using Active Imagination was unexpected. Only much later did I discover there was a name for the continuing experience. Since then I wrote a record of it which is now an eBook. “Call to the Inland.” by Margaret Needham. Amazon Kindle.