There are a number of human experiences that are characterized by presentness, detail, externality, and three-dimensional explorable spacefulness: we can call these visionary experiences. These can be characterized along two dimensions — according to the degree to which the experience is entered into intentionally, and by the amount of control the experiencer exercises over its content. Such visionary experiences appear to be quite widespread across cultures, and raise significant psychological and ontological questions.

Chinese philosophy — perhaps because of its origins in practical political thought — has been dominated by questions of change: why is there change rather than stability? what is the relationship between change and human action? are there patterns of change that we can detect and use to our advantage? The concept of the wŭxíng 五行 was proposed by the philosopher Zou Yan 鄒衍 (fl. c. 350-270 BCE) as one answer to that last question. The idea has become central to Chinese culture.

Of all the claims for the power of ayahuasca to heal sicknesses of various kinds, from cancer to asthma, the most popular current claim is that ayahuasca can — in some sense — cure addiction. There are certainly anecdotes, claims, and uncontrolled self-report studies that can at best be called preliminary. But I have seen no substantial scientific evidence that ayahuasca can successfully treat addictions. Here is why I am cautious about such claims.

The meridians — also called channels, pathways, and other names — are a central concept of Chinese medicine.They are the way that the zàngfǔ or organs extend their regulative processes throughout the body. But the meridians — like the zàngfǔ — are not themselves anatomical objects. Rather, they are streams of qì as experienced from within the lived body.

Some time ago, on a discussion group, a woman posted that she had been sexually assaulted by a shaman at an ayahuasca retreat center in the Upper Amazon. During the course of the occasionally heated discussion that followed, I took the position — which I still maintain — that it is unethical for a shaman to have sex with a patient under any circumstances, even when the sex is apparently consensual. I reproduce the relevant portions of my posts here.

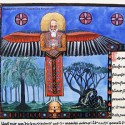

Eidetic visualization — the creation of a minutely detailed mental image of the deity being contemplated, along with the deity’s palace, retinue, appurtenances, and the subtle deities distributed on the divine body — lies at the heart of Tibetan tantric meditation. The practice is ultimately linked to a wave of visionary devotionalism that began in India in the early centuries CE, affecting both Buddhism and the Hindu Vaiṣṇava tradition. The Buddhists, with long practice in eidetic visualization, have important things to say about visionary ontology.

Carl Jung believed that active imagination is a channel for messages from the unconscious. Most important, the dialogue with the contents of the unconscious is with persons — “exactly as if,” says Jung, “a dialogue were taking place between two human beings with equal rights.” Active imagination enters its own visionary landscape, often called the imaginal world. Immediately we face the question of the nature and ontological status of the persons we encounter there.

On November 16, 2009, after a brief illness, famed visionary artist Pablo César Amaringo died at his home, surrounded by friends and family, and leaving behind a mass of uncatalogued paintings and hastily jotted notes. We are more than fortunate that Howard Charing and Peter Cloudsley had already been working with Amaringo for months to get his collection in order, annotate his more recent work, create a digital archive of his art, and protect his paintings from deterioration in their humid tropical environment.

Browse the Full Collection of Articles

- Visionary Experiences

Mar, 2014 - On Chinese Medicine: The Five Xíng

Mar, 2014 - Ayahuasca and Addiction

Mar, 2014 - On Chinese Medicine: The Meridians

Mar, 2014 - Sex with the Shaman

Jan, 2014 - Visualization Before Tantra

Jan, 2014 - Dreaming with Open Eyes

Jan, 2014 - The Shamanic Art of Pablo Amaringo

Jan, 2014 - The Anthropology of Consciousness

Jan, 2014 - Body Practice

Dec, 2013 - The Hunger Artist

Dec, 2013 - Sometimes It Rains

May, 2013 - You Can’t Call 911 in the Jungle

Oct, 2012 - Ayahuasqueros

Aug, 2012 - A Peyote Joke

Aug, 2012 - A New Ayahuasca Study

Aug, 2012 - Vodka, Ayahuasca, Found Footage

Aug, 2012 - Is Ayahuasca Neurotoxic?

Jul, 2012 - Fourteen Dead Shamans

Jul, 2012 - Thinking About Death III: Stories

Jun, 2012 - Thinking About Death II: Levinas

Jun, 2012 - Thinking About Death I: Heidegger

Jun, 2012 - Ayahuasca and the Grotesque Body

May, 2012 - What Do the Spirits Want from Us?

May, 2012 - Traveling Safely to Drink Ayahuasca

May, 2012 - On the Origins of Ayahuasca

Apr, 2012 - The Collective Unconscious

Sep, 2009 - Amazonian Gastronomy

Sep, 2009 - Metamorphosis

Sep, 2009 - Sacred Mushrooms of Mexico

Aug, 2009 - A Love Story

Aug, 2009 - Sex and Violence in Amazonia

Aug, 2009 - The Gift of Diabetes

Aug, 2009 - Susun Weed, Herbalist

Aug, 2009 - Amazonia Barbie

Aug, 2009 - Heidegger the Shaman

Aug, 2009 - Salvia on Schedule

Aug, 2009 - Plants of the Ancient Maya

Aug, 2009 - The Shulgin Documentary

Aug, 2009 - The Mystery of Ulluchu

Aug, 2009 - Painting the Plants with Light

Aug, 2009 - Krippner on Ayahuasca

Aug, 2009 - Nip/Tuck

Aug, 2009 - Spirit Stuff

Aug, 2009 - Sacred Justice, Part 1

May, 2009 - Wounds in the Jungle

Mar, 2009 - Bioneers

Mar, 2009 - Eagle Feathers

Mar, 2009 - The Last Man

Mar, 2009 - Handling Infections

Mar, 2009 - Green Power

Mar, 2009 - A Victory for Santo Daime

Mar, 2009 - The War on Coca Leaves Redux

Mar, 2009 - Hyperthermia

Mar, 2009 - Peyote Songs

Mar, 2009 - Dealing with Snakebite II

Mar, 2009 - Dealing with Snakebite I

Mar, 2009 - The Psychedelic Review

Mar, 2009 - A New Ayahuasca Book

Mar, 2009 - Listening to the Dreamer

Mar, 2009 - Clean Water

Mar, 2009 - Jungle Madness

Mar, 2009 - The Magic Mosquito Net

Mar, 2009 - Native American Film Festival

Mar, 2009 - Ayahuasca and Mental Health Among the Shuar

Mar, 2009 - Mark Your Calendar

Mar, 2009 - Primer Festival de la Selva Peruana

Mar, 2009 - El Dorado

Feb, 2009 - Yuwipi Man

Feb, 2009 - Animated Ayahuasca

Feb, 2009 - Telling Dreams

Feb, 2009 - Literary Shamanism

Feb, 2009 - The Natufian Shaman

Feb, 2009 - How to Build a House

Feb, 2009 - Soul Ayahuasca

Feb, 2009 - Good Blog: Legitimos Guerreritos

Feb, 2009 - A Golden Guide to Hallucinogenic Plants

Feb, 2009 - Jaguar on Ayahuasca

Feb, 2009 - The Dimethyltryptamine Receptor

Feb, 2009 - Indigenous Top-Level Domains

Feb, 2009 - Psychoactive Plants Online

Feb, 2009 - Psychointegration

Feb, 2009 - Philip Glass on the Amazon

Feb, 2009 - Curing

Feb, 2009 - The Great Amazon Raft Race

Feb, 2009 - Two Songs of My Teacher

Feb, 2009 - The Telepathy Meme Again

Feb, 2009 - Hallucinogens and Pornography

Feb, 2009 - Soccer

Feb, 2009 - The Survival of Plant Knowledge

Feb, 2009 - Conference Notes

Feb, 2009

- Weeds

Feb, 2009 - The Importance of Plant Knowledge

Jan, 2009 - Jungle Music

Jan, 2009 - Best New Product of 2009

Jan, 2009 - Pierre Clastres

Jan, 2009 - Entheogen: The Movie

Jan, 2009 - Magic Stones

Jan, 2009 - Fire on the Mountain

Jan, 2009 - Long-Term Peyote Use

Jan, 2009 - Ayahuasca and Cancer

Jan, 2009 - In Search of the Divine Vegetal

Jan, 2009 - Extreme Celebrity Ayahuasca

Jan, 2009 - Jacques Mabit

Jan, 2009 - Terence McKenna on Hope

Jan, 2009 - Good Blogs: Psychedelic Research

Jan, 2009 - An Experiential Typology of Sacred Plants

Jan, 2009 - Heirloom Snuffing Kits

Jan, 2009 - The Single Active Molecule

Jan, 2009 - Ancient Andean Hallucinogens

Jan, 2009 - The Amazon River

Jan, 2009 - An Ayahuasca Documentary

Jan, 2009 - Uncontacted Tribes Again

Jan, 2009 - Uncontacted Tribes

Jan, 2009 - Moses and Ayahuasca

Jan, 2009 - Xanadu Xero’s Challenge

Jan, 2009 - Ayahuasca and Transient Psychosis

Jan, 2009 - The Tragic Cosmovision

Jan, 2009 - Whole Earth Review

Jan, 2009 - Classifying Plants

Jan, 2009 - Perspectivism

Jan, 2009 - Ayahuasca: National Cultural Heritage

Jul, 2008 - A Parable

Jul, 2008 - Policing Sorcery

Jun, 2008 - Shamanism and Rubber

Jun, 2008 - Vance Gellert

Jun, 2008 - Venefices

Jun, 2008 - Strassman Redux

Jun, 2008 - Endogenous Dimethyltryptamine

Jun, 2008 - Jungle and Rainforest

Jun, 2008 - Hallucinogens in Africa

May, 2008 - More Legal Stuff

May, 2008 - Going Fishing

Apr, 2008 - Animated Shamanism

Apr, 2008 - Shamanism Conference

Apr, 2008 - Learning to Sing

Apr, 2008 - Snakebite

Apr, 2008 - Video Amazonia Indigena

Apr, 2008 - The Tragedy of Don Carlos

Apr, 2008 - How I Became a Sorcerer

Apr, 2008 - Two Articles

Apr, 2008 - Sasha Redux

Apr, 2008 - Beta-Carbolines

Apr, 2008 - The War on Drugs

Apr, 2008 - Self-Control

Mar, 2008 - Why Dogs Do What They Do

Mar, 2008 - Two Coyote Poems

Mar, 2008 - Daniel Mirante

Mar, 2008 - Some Announcements

Mar, 2008 - The War on Coca Leaves

Mar, 2008 - Some Thoughts on DMT Art

Mar, 2008 - The Jungle Cookbook

Mar, 2008 - Terry Riley’s Peyote Ceremony

Mar, 2008 - Virotes

Mar, 2008 - Visionary Information

Mar, 2008 - Shamans and Herbalists

Feb, 2008 - Prestige and Hierarchy

Feb, 2008 - Brujo

Feb, 2008 - Shamanic Specializations

Feb, 2008 - Animist Sculpture

Feb, 2008 - The Tragedy of Maria Sabina

Feb, 2008 - Hallucinogens in North America

Feb, 2008 - Hallucinogens in Siberia

Feb, 2008 - The Hallucinogen Culture Area

Feb, 2008 - What Are Spirits?

Feb, 2008 - Protective Spirits

Feb, 2008 - A Death in the Jungle

Feb, 2008 - Plant Knowledge

Feb, 2008 - The Chacra

Feb, 2008 - Beat Ayahuasca

Feb, 2008 - How Plant Spirits Appear

Feb, 2008 - Women and Ayahuasca

Feb, 2008 - Shrooms

Feb, 2008 - Ayahuasca Mainstreamed

Feb, 2008 - Selling Spirituality

Feb, 2008 - Magic

Feb, 2008 - Canaima

Feb, 2008 - Buryat Shamanism Exhibit

Feb, 2008 - Khadak

Jan, 2008 - The Leaf-Bundle Rattle

Jan, 2008 - Three Ceremonies

Jan, 2008 - Indigenists and Universalists

Jan, 2008

- Phlegm

Jan, 2008 - Mishmash

Jan, 2008 - Joe Rogan on DMT

Jan, 2008 - Animism

Jan, 2008 - The Theft of Voice

Jan, 2008 - How Old is Shamanism?

Jan, 2008 - Amazon Baskets

Jan, 2008 - Metachoric Experiences

Jan, 2008 - Eagle and Condor

Jan, 2008 - Shaman Superheroes

Jan, 2008 - Shaman of Colors

Jan, 2008 - Ayahuasca in the Supreme Court

Jan, 2008 - Shamans’ Organizations

Jan, 2008 - Ayahuasca Admixtures

Jan, 2008 - Mermaids

Jan, 2008 - The Ayahuasca Patent Case

Jan, 2008 - Arrow Poisons

Jan, 2008 - Marshall Arisman, Shaman

Jan, 2008 - Sorcery as Political Resistance

Dec, 2007 - New Studies of Psychedelics

Dec, 2007 - Frightened and Stolen Souls

Dec, 2007 - Byron Metcalf

Dec, 2007 - Listening to Dreams

Dec, 2007 - Beings of the Air

Dec, 2007 - Dye Plants

Dec, 2007 - Dolphins

Dec, 2007 - Peter Gorman on the Plant Spirits

Dec, 2007 - Camalonga

Dec, 2007 - The Telepathy Meme

Dec, 2007 - Chullachaqui

Dec, 2007 - The Water People

Dec, 2007 - The Idea of the Wilderness

Dec, 2007 - The Tigress of the Jungle

Dec, 2007 - Control of the Spirits

Dec, 2007 - Shamanism and Conjuring

Dec, 2007 - Pantheism

Dec, 2007 - DMT: The Movie

Dec, 2007 - Panpsychism

Dec, 2007 - Alien Dreamtime

Dec, 2007 - More on Protecting Peyote

Dec, 2007 - Burundanga

Dec, 2007 - Soundscape

Dec, 2007 - Eliade’s Shamanism

Dec, 2007 - Cleansing the Pope

Dec, 2007 - Remembering the Plants

Dec, 2007 - Another Icaro, Modernized

Dec, 2007 - Who is an Indian?

Dec, 2007 - Strong Sweet Smells

Dec, 2007 - Protecting Peyote

Dec, 2007 - Ethical Wildcrafting

Dec, 2007 - Blueberry

Dec, 2007 - Who is a Shaman?

Dec, 2007 - Plants and Spirits

Dec, 2007 - Steam Baths

Dec, 2007 - Suri

Dec, 2007 - Olivier Messiaen

Dec, 2007 - Pucalupuna

Dec, 2007 - The Journals of Knud Rasmussen

Dec, 2007 - What Can Shamans Heal?

Dec, 2007 - The Smell of the Jungle

Dec, 2007 - Chiricsanango

Dec, 2007 - Male Potency Enhancers

Dec, 2007 - The Cushma

Dec, 2007 - Norval Morrisseau (1931-2007)

Dec, 2007 - Courage and Power

Dec, 2007 - Extraordinary Anthropological Experiences

Dec, 2007 - The Society for the Anthropology of Consciousness

Dec, 2007 - Hallucinogen Studies in Animals

Dec, 2007 - Knowing Where to Suck

Dec, 2007 - DMT Delivery Systems

Dec, 2007 - Ayahuasca and Schizophrenia

Dec, 2007 - The Omnipresence of the Spirits

Dec, 2007 - The Saga of Rick Strassman

Dec, 2007 - Sucking

Dec, 2007 - The Future of Shamanism in the Amazon

Dec, 2007 - Richard Doyle on Ayahuasca

Dec, 2007 - The Shamanic State of Consciousness

Nov, 2007 - The Journal of Shamanic Practice

Nov, 2007 - A New Study of Icaros

Nov, 2007 - The Shamanic Crisis

Nov, 2007 - Shamanism and Belief

Nov, 2007 - Visionary Tobacco

Nov, 2007 - Amazonian Pipes

Nov, 2007 - Sex and the Plant Spirits

Nov, 2007 - Do Shamans Heal?

Nov, 2007 - The Dark Lady

Nov, 2007 - Testing the Spirits

Nov, 2007 - Vomiting

Nov, 2007 - Celebrity Endorsements

Nov, 2007 - Icaros, Modernized

Nov, 2007 - Shamans and Soul

Nov, 2007