|

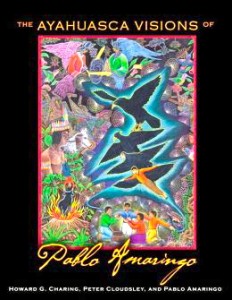

On November 16, 2009, after a brief illness, famed visionary artist Pablo César Amaringo died at his home, surrounded by friends and family, and leaving behind a mass of uncatalogued paintings and hastily jotted notes. We are more than fortunate that Howard Charing and Peter Cloudsley had already been working with Amaringo for months to get his collection in order, annotate his more recent work, create a digital archive of his art, and protect his paintings from deterioration in their humid tropical environment. One result of these dedicated labors is the remarkable book you now hold in your hands.

Pablo Amaringo first became known outside his native Pucallpa with the 1991 publication of the beautifully produced book Ayahuasca Visions: The Religious Iconography of a Peruvian Shaman, a collection of his paintings depicting visions he had received during his years of practice as an ayahuasquero. Ayahuasca Visions is accompanied by his own explanation of each painting and the annotations of anthropologist Luis Eduardo Luna. Entirely self-taught, Pablo had begun his painting career with portraits and meticulously detailed Amazonian landscapes; from the mid-1980s on, with Luna’s encouragement, he dedicated himself to painting his recollections of his ayahuasca journeys.

In contrast to the abstract patterns of indigenous ayahuasca-inspired art, Pablo’s work is characterized by detailed and naturalistic depictions of the substantive content of his visions — the spirits, trees, animals, intergalactic travelers, underwater cities, crystal palaces, spaceships, wise shamans from other planets, sorcerers, and spirit boats revealed to him by ayahuasca — as well as naturalistic depictions of the shamans, patients, audiences, healings, and jungle settings of the ayahuasca ceremony itself.

His art almost paradigmatically falls within what has now come to be called “outsider” art, sometimes “naïve” art, and sometimes “visionary” art. It is direct, intense, dense with content and bright with color; the perspective is nonscientific and two-dimensional. Where there is a narrative, the events are presented simultaneously, within the same frame. His painting is enormously detailed, personal, idiosyncratic, and visionary.

|

| Peter Cloudsley (from left), Pablo Amaringo, and Howard Charing |

One such vision directed Pablo to use his artwork to speak of the spirit world and the difficult times faced by humanity. As a result, in 1988 he founded the Usko Ayar Amazonian School of Painting in Pucallpa, dedicated to documenting the ways of life in the Amazon. The school’s mission was the education of local youth in the care and preservation of the Amazonian ecosystem. They were taught to visualize internally what they were going to paint — to evoke visions, like those of ayahuasca, which could be shared with others.

The work of the Usko Ayar school has been extremely influential, creating a distinctive and recognizable style — particularly landscapes characterized by extremely detailed and naturalistic renderings of jungle plants and animals — and an international market for Amazonian art. What we can now call New Amazonian art — not only of Pablo Amaringo and his students at Usko Ayar, but also of such independent practitioners as Elvis Luna, Yando Ríos, and Francisco Montes Shuña — is finding its way to a global audience and into the commercial art market, through exhibits, both academic and commercial, and through the Internet.

This accessibility has in turn created a strong interest in ayahuasca visions generally, stimulated ayahuasca tourism, and created local markets in Iquitos and Pucallpa for paintings in the Amaringo visionary style. I think it is fair to say that the surge of foreigners seeking out ayahuasqueros in the Amazon, beginning in the mid-1990s, was driven in large part by Pablo’s extraordinary paintings. Indeed, as depictions of ayahuasca experiences have grown normative, it may be that in addition to the experience prescribing the art, the art is prescribing the experience.

|

| Young students at the Usko Ayar Amazonian School of Painting in Pucallpa |

Of equal importance with his art, Pablo introduced us to an immensely rich, complex, and voraciously absorptive mestizo shamanism in what was then the remote jungle of the Upper Amazon. His striking visionary paintings were filled with battleships protected by pyramid-shaped lasers; electromagnetic boa constrictors; spaceships from the edge of the universe; poisonous space snakes from Mars; spaceships from Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Ganymede; beings from distant galaxies with skin as white as paper; singing spaceships from the constellation Kima; magnetizing mirrors; and, of course, doctors and nurses performing spiritual medical procedures.

Similarly remarkable was the way in which Pablo’s own thinking absorbed and then transformed outside philosophical influences. The spirits depicted in his visionary paintings include Krishna, Vishnu, Shiva, and “the great gurus of India.” The Indic word samādhi turns up in the name of Queen Samhadi the Illuminated; and we may see the Indic word kuṇḍalinī in the name of the spirit King Kundal. Buddha appears as a spirit who is a “celebrated king of the Sakias,” or as a “great Chinese guru . . . from the great family of the Sakias.”

This is not a remote and insular shamanism of the sort constructed by anthropologists. Rather, Pablo inherited and expressed a shamanism that had been enmeshed — probably for generations — in all the currents of the modern world, borrowing and reshaping them according to its own vision.

And the paintings are irreducibly shamanic. Indeed, Pablo says that what he produces are more than paintings; they are crystallized ícaros, the magical songs of the mestizo shaman. The paintings have ícaros sung into them as though they were medicine. He explains: “I chant ícaros when I paint, so if ever a person wishes to receive teaching or healing, they should cover the painting with a cloth for two or three months. On the day they remove the cover, they should prepare themselves by bathing and meditating. When it is uncovered they will receive the power and knowledge of the ícaros that were sung into it.”

We are now, thanks to Charing and Cloudsley, in a position to trace Pablo’s trajectory during the intensely productive decades following Ayahuasca Visions.

|

| At Pablo Amaringo’s funeral (photo by Howard G. Charing) |

The art itself has remained essentially the same — colorful, packed with detail, showing events unfolding simultaneously — although perhaps experimenting more with three-dimensional modeling, particularly of the human face. The content remains eclectic. He still speaks about electromagnetic nets, stellar fields, UFOs from another galaxy, flying saucers, and Queen Samhadi; he still depicts the now more familiar creatures of Upper Amazonian mestizo folklore — dolphins, mermaids, magic stones, and wandering spirits of the dead.

And he maintains as well the tremendous richness of his imagery. He has continued to extend his mythological reach; he now depicts angels, Christ, and Confucius ascending the stairway to heaven, as well as unicorns and gnomes. He draws from everything he has seen or read or heard about in conversation with the foreigners who flock to him, as well as from the seemingly inexhaustible mythic resources of the Upper Amazon and his own endless imagination.

What has changed most is the quality of his annotations. His descriptions are now less academic, less anthropological, more personal. He is now more willing to talk philosophically; he no longer fears being misinterpreted or criticized as being insufficiently Catholic. This is perhaps due to the growing strength of his own voice over the intervening decades. His fame has given him opportunities to interact outside the relatively narrow social and religious constraints of Pucallpa, which remains, in many ways, a small town. And I think it is due, too, to his deep personal relationship with Howard Charing and Peter Cloudsley, within which he felt free to express himself more than ever before.

|

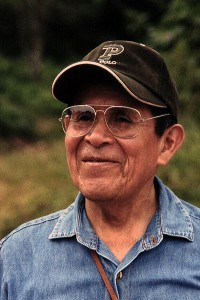

| “Goodness is greater than justice” — Pablo Amaringo (photo by Jon Hanna) |

It is here that the personality of the artist shines through. Pablo had always been a kindly, humorous, and self-effacing man; these qualities are particularly evident here. Throughout his notes he articulates the ideal of confianza: human relationships of mutuality, trust, and generosity. He says, for example: “People will often claim to carry out justice, but usually it is little more than an agreed boundary, one side of which belongs to you, the other to your neighbor. Goodness, on the other hand, is having just enough food for yourself, but still you share it with your neighbor. Goodness is greater than justice. You give of yourself. It makes demands on your heart but you feel happy.”

Howard Charing and Peter Cloudsley are uniquely qualified to put together all of this new material. They have long experience working with shamans in the Upper Amazon and have published dozens of interviews with them; Howard coauthored a book on Amazonian plant spirit medicine, for which Pablo Amaringo wrote the foreword. We owe them our gratitude for guiding us deeper into the art, the thought, and the spiritual world of this wise and gentle artist.

- Previous Post: The Anthropology of Consciousness

- Next Post: Dreaming with Open Eyes

- More Articles Related to: Ayahuasca, Books and Art, Shamanism, The Amazon