Not the Perennial Philosophy

Many of the common assumptions about the ultimate aims of spiritual practice — both in India and, indeed, generally — have been profoundly influenced by the teachings of an aristocratic nineteenth-century Hindu monk named Narendra Nath Datta, better known by his religious name of Swāmī Vivekānanda.

|

| Swāmī Vivekānanda |

In 1893, Vivekānanda spoke for India at the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago, and his message of religious unity received a two-minute standing ovation from a crowd of seven thousand. It was largely through the charisma of Vivekānanda that the highest form of Indian spirituality came to be associated in the west — apparently irrevocably — with advaita Vedānta, leaving in the colonial dust the troublesome mess of dualisms, qualified nondualisms, and nondual dualisms — dvaita, viśiṣṭādvaita, avibhāgādvaita, bhedābheda — and the luxuriant theisms that constituted unexported Hindu spirituality.

Vivekānanda had been the leading disciple of the celebrated Hindu saint Śrī Rāmakrishna. When Rāmakrishna died in 1866, his followers, including Vivekānanda, had founded the Rāmakrishna Order of monks. After Vivekānanda’s triumphal American tour, the Rāmakrishna Order established several Hindu missions in America, primarily on the west coast; and it was in the late 1930s and early 1940s, in the Los Angeles Vedanta Center, that Swāmī Prabhāvānanda — disciple of Swāmī Brahmānanda, in turn a disciple of Rāmakrishna himself — influenced an eccentric literary circle that included Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood, and Aldous Huxley (see generally Beckerlegge, 2001; Washington, 1995, pp. 309-333).

In 1944, Huxley published The Perennial Philosophy, which proposes that there is a “common core” or philosophia perennis underlying all religions. There are two principal themes of this perennialism. The first is that all religions, ultimately, say the same thing; and the second is that what they say is that the individual soul and the divine soul of the universe are unequivocally one — precisely the advaita Vedānta of Swāmī Vivekānanda.

All faiths, Vivekānanda had written, “are but various phases of one eternal religion… expressing itself in various countries in various ways” (quoted in Vajraprana, 2000). Huxley says the same — that the perennial philosophy “in its fully developed forms… has a place in every one of the higher religions… The inexhaustible theme has been treated again and again, from the standpoint of every religious tradition” (1944/1970, p. vii).

And central to this one eternal religion is the claim that there is, as Huxley puts it, “a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds,” that there is “in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality” (1944/1970, p. vii). This is the tat tvam asi “That art thou” philosophy of Vivekānanda’s export version of advaita philosophy. Perennialist Ken Wilber puts it this way — that “human personality is a multi-leveled manifestation or expression of a single Consciousness… which ranges from the Supreme Identity of cosmic-consciousness through several gradations or bands to the drastically narrowed sense of identity associated with egoic consciousness.” Thus, “our ‘innermost’ consciousness is identical to the absolute and ultimate reality of the universe” (1993, p. 22). But we forget this identity and fall into duality. “We divide reality,” Wilber says, “forget that we have divided it, and then forget that we have forgotten it” (1977, p. 241).

|

| Aldous Huxley, author of The Perennial Philosophy |

There is much yet to be written regarding the romantic appropriation of Hinduism by the west, and the part played in that colonial discourse not only by western perennial philosophers but by Hindu intellectuals such as Swāmī Vivekānanda and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. There was — and continues to be — a lot at stake on both sides in seeing advaita Vedānta as typifying the ancient, noble, and ascetic spirituality of the Hindu people, especially given advaita Vedānta’s own colonizing discourse — that advaita is the culminating Hindu philosophy, under which all others, including Buddhism, can be conveniently and hierarchically arranged (see generally King, 1999, pp. 118-142).

These claims have so thoroughly entered our thinking about the goals of spiritual practice as to be unremarkable. But it is my contention that important soteriological traditions contradict the perennial philosophy, and, indeed, say precisely the opposite — that salvation lies not in realizing the unity of self and universe, but rather in achieving a monadic isolation of the self. These traditions see an ultimate and irremediable duality between an inherently pure self and a defiling universe. Thus there have been in India at least two very different soteriological paradigms — on the one hand, a paradigm of immanent insight, which saw liberation in cognitive penetration into the source and meaning of events in the world; and, on the other, a paradigm of transcendent isolation, which saw liberation as total disconnection from all events and all experiences.

Perennialism, like neo-Vedānta, has two strategies to deal with soteriological claims for transcendent isolation. First, it can place such claims hierarchically beneath the true soteriological experience of supreme identity; other views are claimed to be merely steps on a ladder leading to the ultimate nondual realization. Hindu polemics have, in fact, utilized this device for centuries. Or, second, it can claim that immanent insight and transcendent isolation are, when read correctly, really the same, just as Wilber can assert that Allah and Tao are merely two different words for the same thing (1993, p. 22).

This latter argument is appealing, because it is essentially irrefutable; the proponent simply accuses the dissenter of spiritual obtuseness. But I think that any fair reading of the texts shows that the two experiences are phenomenologically distinct, and our understanding of meditative traditions in general — and those of India in particular — is ill-served by perennialist strategies to deny it.

The Paradigm of Immanent Insight

The Quest for Insight in the Vedas

In order to interpret the texts that discuss transcendent isolation, it is important first to understand, in their cultural context, the texts that describe immanent insight, since isolation is often contrasted with insight — or, indeed, sometimes just sight — either directly or symbolically. Thus, in the Vedic universe, the seer (ṛṣi) — trembling with his poetry, sharpened by soma — is, literally, the one who sees. The vision of the seer “wanders to far distances” (Ṛg-veda VI.9.12). The seer Dīrghatamas, whose name means “long darkness” and who is traditionally held to have been born blind, sees in just this sense; he seeks with his mind the footprints of the gods (I.164.5); he sees that “this altar is the farthest end of the earth, our sacrifice is the center of the world” (I.164.35). “He who has eyes,” he says, “may see this” (I.164.16).

And the poetic vision extends also to the past, to the origins of things. “With my mind as an eye,” says one poet, “I believe I see those who as the first performed this sacrifice” (X.130.6). Dīrghatamas sees how the “long-haired heroes” perform the primal sacrifice of soma (I.164.43-46) “with mental vision, their thoughts trembling” (I.164.36).

The poet thus knows things that are hidden from those who cannot see: he has traced the origins of things (X.114.2) and knows the connections between what is and what is not (X.129.4); the seer guards the track of things “as they are” and “keeps the highest names of things concealed” (X.5.2). It is the poets who are asked the number of fires and suns, of dawns and waters (X.88.18), and are questioned on the origins of heaven and earth (I.185.1).

This special visionary knowledge of the connections of things is often expressed by nominal and verbal forms derived from the Sanskrit root √vid “know.” Dīrghatamas goes to the poets “for knowledge” (vidmane, I.164.6); few are those who “know the hidden way of things” (yad guhā tad addhātaya id viduh, X.85.16); the poet “truly knows” (addhā veda, III.54.5) and will declare the pathway leading to the gods.

Around 800 BCE there began the composition of the Brāhmaṇas, compendious prose analyses of the Vedic rituals. The purpose of these texts is to make clear the connections between the ritual process and the cosmic order: they form, in effect, a lexicon of metaphor. The successful sacrifice had always been one in which all of time and space intersected in the seeing of the sacrificer. Already in the cosmogonies of the tenth book of the Ṛg-veda there had been speculation that all the gods and even the universe itself came from one thing, came from that. But now to know this single thing — this most important thing in the world — would be to know at once all the connections that bound the world together. To know that — whatever it might be — would unlock the dimly perceived hidden pattern of the world: to know that would be to own the world, and gain the ultimate freedom.

The quest is thus for knowledge of one thing — the most important thing in the world. This is what the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (VI.1) calls “that one thing by knowledge of which all this is known,” and of which the Praśna Upaniṣad (IV.11) says: “One who knows the imperishable knows all things and enters into all things.” When the Buddha, in Majjhima-nikāya I.171, declares to the wanderer Upaka that he is omniscient (sabba-vidū), the claim is not so much that he knows everything as that he knows the one thing. Knowing this, Buddha has become “the conqueror of the unending.” He has penetrated into the link that connects all links: he has perceived — to put it again in Upaniṣadic rather than Buddhist terms — “that across which space is woven like warp and woof,” which the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (III.8.7-8) calls the imperishable: “It neither eats nor is eaten.”

Seeing and Eating

It is important to take note of an implicit epistemological metaphor in all this: to see — to know — is to eat. Conversely, to starve is to cut off sensory interaction with the outside world. Thus the poet, in knowing the world, consumes it. “For one who knows this (evamvidi),” we read in the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (V.2.1), “there is nothing which is not food.” In Ṛg-veda X.125.4 the goddess Speech (vāc) declares of herself: “Through me alone all eat the food that feeds them.” And again: “One who knows this,” says the Taittirīya Upaniṣad (III.10.5), “goes up and down these worlds, eating what he desires, assuming what form he desires. He sits singing this chant: O wonderful! O wonderful! O wonderful!”

I am food, I am food, I am food!

I am an eater of food, an eater of food, an eater of food!

I am a maker of verses, a maker of verses, a maker of verses!

I am the firstborn of reality, earlier than the gods, in the navel of immortality:

who gives me away truly keeps me.

I am food. I feed on the feeder of food. I have overcome the whole world!

Thus the seer perceives a final truth about the cosmos: it is food. The Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa (II.8.8) declares:

Food is the exhaling breath, food the inhaling breath:

food they call death, the same food they call life.

Food the brahmans call growing old,

food they also call the begetting of children …

I the food am the cloud, thundering and raining.

They feed on me: I feed on everything.

I am the undying, the essence of the universe.

By my force all the suns in heaven are aglow.

“Great is his greatness,” says the Chāndogya Upaniṣad (IV.3.7), “for he eats what is not food, without being eaten.” And note the converse: “Death,” says the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (X.6.5.1), “is hunger.”

Upaniṣadic Vidyās

Somewhere within the world, then, is this imperishable truth, this single knowledge. The technique was to trace this single thing through chains of dependence, seeking the ultimate reality on which all else rested. Typical is the dispute of the senses in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad VI.1.71-74 and Chāndogya Upaniṣad V.1.6-15: to decide their priority, each sense departs the body for a year. The speech leaves the body mute, the eye leaves it blind, the ear deaf, and the mind “as a mindless child,” yet the body still lives. But when the breath departs, it pulls the others with it “as a fine horse pulls up the pegs to which its feet are tied.” The senses then make offering to the breath, for it alone is indispensable, and is the foundation of them all.

Many of the most important sections of the Upaniṣads consist in such dialogues or contests wherein faculties or forces compete to see which is the most effective and hence most real, or in which the participants try to identify — to see, to know — ever more fundamental aspects of the world. In some cases a whole series of similar identifications is proposed by one interlocutor and rejected by the other as insufficiently basic. In Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad II.1.1-20, the brahman Bālāki Gārgya, for a fee of a thousand cows, proposes to teach King Ajātaśatru about ultimate reality: he identifies it as the person in the sun, the person in the lightning, the person in a mirror, the sound that follows when one walks, the shadow, the person in the body. The king rejects them all: what he seeks is the awareness which in dreamless sleep lies in the heart, from which come forth all the worlds and all the gods, as a thread comes forth from a spider or a spark from a flame.

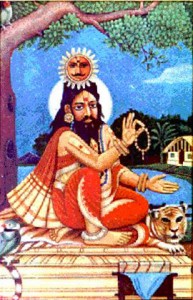

|

| The sage Yājñavalkya |

Again, in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad IV.1.1-7, King Janaka of Videha sets out identifications he had learned from several masters: the most important thing in the world is speech, breath, sight, mind. The seer Yājñavalkya dismisses them, showing that each has an “abode” and a “support.” Whatever depends upon another is but a “one-legged reality.”

In many cases the quest is carried through dialectical chains, whose links show a variety of conceptual and causal dependence relationships. King Janaka asks a reluctant Yājñavalkya to tell him “what light a person has” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad IV.3.1-6). The light of the sun, he is told, but he is unsatisfied: what light has a person when the sun has set? The moon, he is told: and when the moon sets one has fire, and when the fire goes out one has speech. But what light has a person when speech is hushed? This one’s light, the final answer comes, must be the self, the light within the heart.

Similarly, in Chāndogya Upaniṣad I.8.1-9.2, the chant is traced back to sound, sound to breath, breath to food, food to water, water to the other world, the other world to this world, and this world to space: “All things here arise from space, and into space they disappear again. Space is greater than these: space is the final goal.” The entire seventh chapter of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad is an ascending chain of entities ever more vast, until identification is made with immortal vastness itself, founded only upon its own greatness; and in Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad III.6.1 each link in the chain is “woven” upon the preceding one “like warp and woof.” The chain may also be read forward as a causal sequence, as we find in Taittirīya Upaniṣad II.1.1: “From the self arose space, from space wind, from wind fire, from fire water, from water earth, from earth plants, from plants food, from food semen, and from semen the person.”

Such identifications constitute the text of Upaniṣadic meditation, and tracing such chains must have been one of the central contemplative techniques in the time of the earliest Buddhist community. The process is called upāsanā “identification” or vidyā “knowledge” — note the root √vid again — and it receives considerable attention in Brahmasūtra III.3, where the great commentators have sought to bring some order to the luxuriant speculative growth of centuries.

What is important for our purposes, however, is not so much the particular identifications, nor even the way they were eventually subsumed under the hierarchical rubrics of orthodox Vedānta, as the contemplative process itself. We have the testimony of Vidyāraṇya and of Appaya Dīkṣita that there once existed manuals of upāsanā, parallel to the practical handbooks of Vedic sacrificial ritual: it is one of the many literary tragedies of ancient India that these have failed to come down to us. Still we may note a common factor in these meditations: the trajectory of the quest passes invariably through the world. The meditator tracks down the ultimate reality immanent within the cosmos by exercising a poetic awareness of the meaning of things.

In the famous vidyā of Śāṇḍilya (Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa X.6.3; Chāndogya Upaniṣad III.14.1-4; Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad V.6.1), for example, the practitioner contemplatively identifies ultimate reality as “that from which one comes forth, that into which one will be dissolved, and that wherein one breathes.” This is the self within the heart — “smaller than a mustard seed” — that yet lies immanent within “all deeds, all desires, all smells, all tastes.” Here the meditator recognizes the true nature of all the things that appear: all events become charged with the meaning of their secret connections, as metaphors for the reality they conceal. The poet has mastered the ultimate metaphor.

Buddhist Vidyās

It is clear that much Buddhist meditation — and, importantly, much Buddhist meditation that has been exported to western countries in modern times — follows the pattern of this sort of vidyā. For example, the well-known Buddhist formula of dependent origination, beginning with ignorance or desire and ending in old age and death, bears a striking resemblance to the causal chains that constitute Upaniṣadic meditation. And there is evidence that the formula was in fact used as a meditative device, with the practitioner contemplatively pursuing the sequence of connections to its final term. Thus we read in the Dīgha-nikāya (II.31-35), for example, that the bodhisattva Vipassi becomes enlightened by meditation on the formula. At the moment of his insight he gains a “vision into things unknown” that yields awareness and knowledge and light. He gains vidyā; he sees the world as it truly is; he is, as the texts put it, liberated by knowledge (Sanskrit prajñāvimukta, Pāli paññāvimutta).

Similar is the well-known exercise called the four applications of mindfulness (Sanskrit smṛtyupasthāna, Pāli satipaṭṭhāna). “There is a way, monks,” we read in Samyutta-nikāya V.41 and Majjhima-nikāya I.55, “that leads only to the purification of beings, to passing beyond sorrow and grief, to the extinction of ill and sadness, to the attainment of right method, to the realization of nirvana – and that way is the four applications of mindfulness.” In this form of Buddhist vidyā, the meditator focuses in turn on the body, feelings, thoughts, and events, and realizes that all the objects of this mindfulness are impermanent, suffering, empty, and essenceless. Here again the meditator recognizes the true nature of all the things that appear, and it is this insight — this seeing — which grants freedom.

The Conflict of Paradigms in the Early Buddhist Community

Susīma and Nārada

|

| Fasting Siddhārtha The future Buddha undergoes the austerities of a nigaṇṭa Gandhāra period Lahore Museum |

Two stories about this contemplative practice seem to have circulated in the early community, with strikingly different conclusions. The first is reported in Saṃyutta-nikāya II.119. The wanderer Susīma is delegated by his heretical colleagues to learn the teachings of the Buddha, so that they too may preach it and thus share in the reverent welcome and abundant gifts provided by the laity. He enters the community as a spy; he is accepted as a disciple and given ordination. He hears the Buddhist monks declare their liberation with the words, “ I know that birth is destroyed, lived is the holy life, done is what was to be done, and there is nothing further beyond this.” He respectfully greets those who have made this declaration and asks them if they — “thus knowing and thus seeing” — possess the manifold magic power: they do not. He asks if they possess the divine ear that hears at a distance: they do not. Similarly he asks if they possess knowledge of the thoughts of others, memory of their past lives, the divine eye that sees beings arise and pass away according to their deeds: they do not. Most important, they do not touch with their bodies the nonmaterial states of liberation wherein matter is transcended. He demands to know how they can declare liberation yet have no such attainment: they tell him that they have been liberated by knowledge. Susīma is puzzled and asks them to elaborate, but they only insist, “Friend Susīma, whether you understand it or not, we have been liberated by knowledge.”

Susīma then goes to the Buddha and tells him all that had happened. The Buddha teaches him about impermanence, suffering, and essencelessness: every constituent of the world must be “seen as it is with true knowledge.” He leads Susīma through the twelvefold formula of dependent origination, forward and backward. When Susīma knows and sees each connection, he is asked the same questions he himself had asked the monks, to all of which he is compelled to give the same answers: he does not touch with his body the nonmaterial states of liberation wherein matter is transcended: he has been liberated by knowledge. Susīma confesses that he came as a thief into the community, and he is forgiven.

The second story is recounted in Saṃyutta-nikāya II.116. The monk Nārada is sitting with the monks Musīla and Saviṭṭha; his companions are discussing dependent origination, and Saviṭṭha asks Musīla whether — “apart from belief and faith, apart from hearsay, apart from approval of a received opinion” — he himself has personal knowledge of the sequence: he leads Musīla step by step through the formula, forward and backward, and at each point Musīla knows it and sees it. “Then the venerable Musīla is liberated,” Saviṭṭha declares, “and his flowing has ceased.” The venerable Musīla remains silent.

Thus far Musīla and Susīma have pursued the same course. They have applied a doctrinal formulation to the events of the world and thus know its causal articulation: liberation is gained by an act of insight into the meaning of things. At this point Nārada enters the conversation. “It would be well to ask me these questions,” he says to Saviṭṭha. “Ask me and I will answer you.” So Saviṭṭha leads him through the formula, and at each point Nārada replies as Musīla had done. “Then the venerable Nārada is liberated,” Saviṭṭha declares, “and his flowing has ceased.”

But Nārada does not remain silent. “I am not liberated,” he says, “nor has my flowing ceased. It is as if there were a well in the desert, but with no rope nor means of drawing the water. A man comes by — overcome with heat, weary, trembling, thirsty — and looks down into the well. Truly he would know that here was water, yet he could not touch it with his body. I have seen as it is with true knowledge that the ceasing of becoming is nirvana; yet I am not liberated, nor has my flowing ceased.”

Knowledge and Witness

The tradition has here preserved in close conjunction two stories with opposite conclusions. The monks interviewed by Susīma had not transcended the realm of material substance; Harivarman, in chapter 194 of his Satysasiddhi (T.1646 XXXII 366c6-368b2), maintains the extreme thesis that the monks had become liberated without entering into any trance at all: that Susīma became liberated upon hearing an exposition on causality would seem to justify his opinion. Susīma and Musīla both know the most important thing in the world; Nārada claims that this is not enough.

The expression “touching with the body” defines an enstatic progression through increasingly subtle realms of trance to a personal experience of the “ceasing of becoming” that is nirvana. It stands over against an insightful penetration into the true nature of things that liberates within the world. Embedded in a standard list of seven types of practitioner there seems to survive an archaic and fundamental distinction — reflected for example in the abbreviated classification of Aṅguttara-nikāya IV.451 — between one who is “liberated by knowledge” (Sanskrit prajñāvimukta, Pāli paññāvimukkha) and one who is a “bodily witness” (Sanskrit kāyasakṣin, Pāli kāyasakkhi). The former knows with knowledge the stages of the trance; the latter touches them with the body.

The same distinction of contemplative modes is found in Aṅguttara-nikāya III.355, where the monk Mahācunda — the younger brother of the incomparable Sāriputta, according to the commentary of Buddhaghosa — rebukes an ongoing dissension in the community. The monks “whose discipline is doctrine” (dhammayogā bhikkhū) are disparaging the monks who practice trance (jhāyī bhikkhū), saying: “These fellows say they enter trance: they go into a trance, they sit in a trance, they stay in a trance. What is this trance they enter? How do they enter it? Why do they enter it?” And the monks who practice trance are in turn disparaging the others, saying: “These fellows say their discipline is doctrine: they are excited, arrogant, unsteady, noisy; they talk too much, they have no concentration, their minds wander, their senses are not controlled. What doctrine is their discipline? How is it their discipline? Why is it their discipline?”

Mahācunda demands that the two factions praise each other. “Friends,” he exhorts them, “you should train yourselves thus: We whose discipline is doctrine shall praise the monks who practice trance. And why? Wonderful are these persons, and hard to find in the world, who touch the immortal realm with their bodies and there abide. Friends, you should train yourselves thus: We who practice trance shall praise the monks whose discipline is doctrine. And why? Wonderful are these persons, and hard to find in the world, who see and penetrate with knowledge the deep way of the goal.”

Wonderful might be those whose discipline is doctrine, and the practitioners of trance conceded that nirvana could be reached by insight alone; but still they had a name, not entirely complimentary, for those who, in Nārada’s words, could see the water but not touch it with their bodies — dry seers (sukkhavipassakā: see Buddhaghosa, Visuddhimagga XXI.112, XXIII.18).

The Paradigm of Transcendent Isolation

The “Unbound Ones”

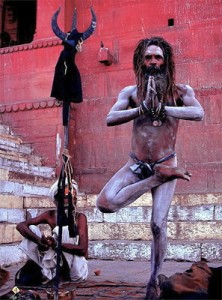

|

| Nigaṇṭas, unbound ones, “stand upright and refuse a seat” (Dīgha-nikāya I.166, III.41) |

King Ajātaśatru — whom we have already met interviewing the brahman Bālāki Gārgya in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad — is credited in Buddhist sources as well with considerable interest in the wanderer sects that flourished in his kingdom. In the Dīgha-nikāya (I.58), the king talks with Nātaputta, a nigaṇṭa or “unbound one,” who speaks enigmatically of a fourfold discipline of suppression, whereby his soul has “departed” and become restrained and unmoving.

In the Majjhima-nikāya (I.92) we are told that the Buddha himself met with “unbound” wanderers claiming Nātaputta as their master. He comes upon them “standing erect, refusing to sit, experiencing feelings that are sharp and painful and severe.” He questions them about their behavior, and they tell him that they are destroying their past evil deeds by painful austerities. By suppression of body and speech and mind they will commit no new evil deeds: by burning up the deeds of the past and by doing no new deeds in the present, they say, there will be no more “flowing” in the future. When there is no flowing, then deeds are cast aside; when deeds are cast aside, the suffering is cast aside; when suffering is cast aside, then feelings are cast aside; and when feelings are cast aside, then all suffering is utterly destroyed.

A similar account is given in Majjhima-nikāya II.218, and again in Aṅguttara-nikāya I.220: the latter text does not speak of the destruction of flowing, but uses instead the expression “the breaking of the bridge.” In this text too the wanderers articulate their goal: “It is by this purifying destruction,” they tell the learned prince Abhaya, “that we pass beyond even in this life.”

The Purifying Heat

Such purifying destruction was a form of heat (tapas), which is gained by holding the breath and retaining the semen; thus the combination of celibacy and heat in Atharva-veda XI.5, where by celibacy and heat the gods ward off death. This is the heat of retention for the purpose of burning away, of purging, while stopping all flow into or out of the body. Here the heat is the purifying furnace of the smith, which burns away the defilements of the world.

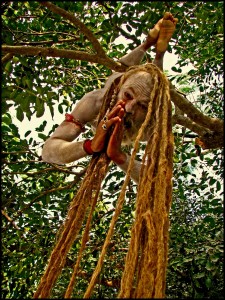

|

| “Such wanderers lay on beds of thorns…” A Yogi in Thorn Bed (photo by ramabhpl) |

Such wanderers lay on beds of thorns, hung head downwards from the branches of trees, held their arms motionless above their heads until the muscles withered and the nails of their clenched fists grew through their palms. Buddhist texts give a standard list of such practices (Dīgha-nikāya I.166, III.41; Majjhima-nikāya I.77, 238, 342). Such practitioners, we are told, go naked, and lick their hands after eating; they do not take food from a pot, nor from a pregnant woman, nor from where a dog stands. They eat but once a day, or once a week, or once every two weeks; they eat rice husks and straw and cow dung. They wear coarse rags, shrouds from the cemetery, or the bark of trees. They pull out their hair and beards, stand upright and refuse a seat, squat down and refuse to stand; they bathe three times a day, or let their bodies gather filth; they eat loathsome food, and drink no cold water.

These acts are a lexicon of enstasis: they are all modalities of hunger. In the Maitrī Upaniṣad I.1-4, King Bṛhadratha goes into the forest and stands with his arms raised, staring at the sun, for a thousand days. The reasons he gives are a catalogue of weariness and disgust:

In this foul-smelling insubstantial body, a conglomerate of bone, skin, muscle, marrow, flesh semen, mucus, tears, feces, urine wind, bile, and phlegm, what is the good of the enjoyment of desires? In this body which is afflicted with desire, anger, greed, delusion, despair, envy, separation from what is desired, union with the undesired, hunger, thirst, old age, death, disease, and sorrow, what is the good of the enjoyment of desires?

And we see that all this is perishing, as these flies and gnats, the grass and the trees that grow and decay… There is the drying up of the great ocean, the falling away of the mountain peaks, the deviation of the fixed stars, the cutting of the ropes of the wind, the submergence of the earth, the departure of the gods: in such a world as this, what is the good of the enjoyment of desires?

|

| “…hung head downwards from the branches of trees…” (photo by Alkeme) |

“All this is food and the eater of food,” says the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (I.4.6); but to the king it is all loathsome food, and he refuses to partake of it. “In this world I am like a frog in a waterless well,” he cries, sweating and filthy beneath the hot sun. “He who feeds on the world returns to it again and again,” he says, seeking to find in his pain a way out of the world that traps him. To the king such hunger is not death: here the image is of the world — of his own body — as filth, and of his inner heat as purging the defilements of the soul: he seeks to refine, to remove the dross, to burn away the world as a smith purifies and forges his metal in the fire. The Jaina Ācāranga Sutra (Prakrit Āyāramga Sutta) (II.16.8) says: “For a liberated wanderer who walks in wisdom, who is constant, who bears pain — his gathered filth vanishes as the dirt covering silver is removed by fire.”

Isolation in the Jaina Sūtras

Suppression and Destruction

These “unbound ones” mentioned in both the Upaniṣadic and Buddhist traditions have been convincingly identified with the Jaina wanderers who flourished alongside the other wanderer sects, and reference to classical Jaina doctrines can shed considerable light on the early practice of transcendent isolation (on the Jaina path generally, see Tatia, 1951, pp. 291-293; Jaini, 1979/1998, pp. 241-273). Thus the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra (Prakrit Uttarajhayaṇa Sūya) — a compilation containing perhaps some of the earliest sacred writings of the Jainas — tells us that “by austerities one cuts off deeds” (XXIX.27); and the text continues (XXIX.37), “By renouncing activity one gains inactivity; by ceasing to act one acquires no deeds, and destroys the deeds that were acquired before.” And again: “Deeds are the root of birth and death, and birth and death they call suffering” (XXXII.7); only one unmoved by sense or feeling is free of suffering, as a lotus is untouched by the mud in which it grows (XXXII.99).

|

| “…held their arms motionless above their heads until the muscles withered” |

Chapters XXXIII and XXXIV of the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra make explicit the axiomatic underlying this austere discipline of inactivity. It is our deeds that impel us upon the round of repeated death: karma — “action” — is viewed as a material substance that “flows” in upon the soul, that “colors” it and weighs it down. This “flowing” of karmic matter is envisioned as a sort of liquid coloring that tinges the inherently stainless and transparent soul, darkening it with the color (Sanskrit leshyā, Prakrit lesā, cognate with the Buddhist Sanskrit kleśa, Pāli kilesa “defilement”) that corresponds to the moral character of the deed. Wicked deeds are black and heavy, and virtuous deeds are lighter in color and in weight: but all deeds equally weigh upon the soul, and keep it bound to the cycle of life and death. As long as a living being moves or changes, says the Viyāhapannatti (III.3), it cannot reach the end of the world.

The wanderers, then, are seeking first the suppression of this karmic flow, and then the destruction of all its traces in the soul. This is the twofold sequence of the Jaina discipline — by extraordinary control and care to impede the influx of defiling karma, and then by a process of starvation to “burn away” whatever darkness may remain. Such “purifying destruction” demands that they close every gate through which new deeds can enter and defile them: they must abstain from action of every kind. The present karma will yield its inevitable suffering, and the adventitious defilement will gradually dwindle; if no fresh particle of karma is allowed to enter, the translucent purity of the soul can gradually be revealed. It is only by heroic striving, says the Viyāhapannatti, that one attains the suppression and destruction of deeds (I.3): but the soul regains its “single state” only when what is yet to be experienced has been destroyed (XIV.4).

Solitude

Here King Ajātaśatru has come upon a path very different from that of Upaniṣadic insight into immanent reality — instead, enstacy, sensory withdrawal, a progressive immobility of body and mind. Where the Upaniṣadic seer sought a way into the world, those who here seek to be “unbound” are trying to find a way out of a world filled with darkness and defilement. They are seeking a “purifying destruction” by which to pass beyond the world and “break the bridge” that links them to it. The aim is to be cut off from the world, to refuse the feast of the senses at which the poet eats. If the seer seeks the dissolution of his ego boundaries, then these “unbound ones” seek to erect total and impenetrable barriers around a monadic and isolated self. If the Upaniṣadic seer masters death by a knowledge of the true nature of things, then these “unbound ones” escape from death by fleeing entirely beyond its grasp, removing the self completely from the world. An uncompromising line is drawn between pure spirit and polluting universe; in this radical dualism, the realm of deathlessness must be transcendent, beyond the defiling swamp of the world and all the reach of sense; it must be totally other.

This description is encapsulated in the very name the Jaina texts give to this freedom from death: it is called kaivalya, “isolation, solitude.” When no coloring remains within the soul, the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra says, the soul “takes the form of a straight line and departs in a single moment, without touching anything and taking up no space.” It assumes its natural form and puts an end to all suffering (XXIX.73). Once the soul has been purified of its accumulated karma, it lifts itself up by its own unimpeded buoyancy to the very top of the cosmos, which is shaped like a colossal human being: there, inside the hollow of the unimaginable head, the soul rests forever in imperturbable solitude, purged of the weight of the karmic matter that held it down. It is deathless and birthless, suspended beyond the great morass of voracious ingestion; it has expelled the universe from itself.

Immobility

|

| Colossal statue of Bahubali, ideal Jaina saint Vines grow on his immobile body Śravaṇa Beḷagoḷa, Karnataka 978-993 CE |

The “unbound one” carries out the discipline of suppression by cutting off all interaction with the world, acting out in the body itself the isolation that is the natural condition of the soul. “Try to realize that you are single and alone,” says the Sūtrakṛtānga Sūtra (Prakrit Sūyagaḍaṅga Sūya) (I.10.12), “for thereby you will gain liberation.”

A striking characteristic of Jaina texts is their emphasis on both harmlessness and celibacy: aggression and desire are the two major modes of involvement with the environment, and both must be suppressed to impede the flow of deeds into the soul. A monk should give no offense to any creature, we read in the Sūtrakṛtāṅga Sūtra (I.10.1-2), whether they move or not, whether above or below or on the earth, by pressing upon them either with hands or feet. “This is the quintessence of wisdom — to kill nothing” (I.11.10): ceasing to injure living beings is called nirvana, which consists in peace (I.11.11). The same text is equally emphatic on celibacy: a sage should restrain his senses from women, and wander about free from all that binds him to the world (I.10.4). Sex and aggression are two sides of the same coin of activity within the world. “Love and hatred are the two evils that produce wicked deeds,” says the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra (XXXI.3), “but one who avoids them will not stand within the round of death.” And the Ācārāṅga Sūtra (I.8.1.16) describes the archetypal Jaina saint: “He practiced the sinless abstinence from killing, and did no deeds, neither himself nor with others; he knew that women were the cause of all wickedness.”

In aggression the body as a whole moves outward to its object; lust is a flow of semen and senses. Suppression thus becomes a matter of retention. In eliminating interchange with the world, the outward flow must be impeded so that the inward flow can be stopped. This isolation from the surrounding world is achieved finally only in a state of absolute physical immobility: a living being can reach the end of the world, the Viyāhapannatti says (III.3), only when it stops moving. The immobile “unbound ones” that the Buddha met were fulfilling a vow of motionlessness such as this (Ācārāṅga Sūtra II.9.5): “I shall not lean against anything: not changing the position of the body, not moving about a little, I shall stand there. Abandoning the care of the body, abandoning the care of the hair of the head, the beard, the nails, the other parts of the body, standing perfectly motionless I shall stand there.” To take such a vow is to begin to break all the bridges that would link the practitioner to the world. It is to begin to unbind oneself.

The Hunger Artist

|

| Ṛṣabha and Mahāvīra Jaina tīrthaṅkaras Naked, upright, immobile, arms not touching the body Orissa, 11th-12th century British Museum |

The practitioner in this tradition is acting out physically the erection of impenetrable barriers between self and world. Where eating is the mythic image of insight into the immanent, then the wanderer who seeks transcendence must starve. This in fact the Jainas did: the fast to death became firmly established as the “wise death” (Sanskrit paṇḍitamaraṇa, Prakrit paṇḍiyamaraṇa) (Viyāhapannatti II.1). To starve is to cut off the flow inward, just as immobility cuts off the flow of the body outward to the world. The rejection of food and the practice of immobility — even to the death — are linked as the most potent expressions of a persistent and stubborn refusal to allow the world access to the soul. To starve the body is to burn away the accumulated defilement of eons: in hundreds, thousands, and millions of years, we read in the Viyāhapannatti (XVI.4), a hell being does not destroy as many deeds as does a monk even by a short fast.

The earliest Jaina texts give detailed instructions for fasting. This may be either temporary or to the death, with temporary fasts of increasing length and severity (Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra XXX.9-13): the fast to death may be accompanied by immobility. When the brahman Khandaga Kaccāyaṇa hears the Jaina teachings from Mahāvīra, the Viyāhapannatti tells us in one of many stories of such “wise deaths” (II.1), he converts and undertakes sixteen months of steadily prolonged fasting, ending in his death: Mahāvīra predicts his final liberation.

The Ācārāṅga Sūtra (I.7.8) describes the wise death that concludes a twelve-year practice of austerities. One must bear the pain of starvation, and not give way to the worldly feelings that overcome one; when crawling insects feed on one’s flesh and blood, one should neither kill them nor rub the wound, nor stir from one’s position. One should not long for life nor wish for death; one should strive after absolute purity. When all flow has ceased, one should bear one’s suffering as if rejoicing in it: when one is finally “unbound,” then one has accomplished one’s life.

To starve to death is to cut oneself off from the world in the most direct and dramatic way. The enstatic contemplative seeks an extravagance of autonomy, a progressive sensory withdrawal from a world whose defiling matter colors the soul. The hunger artist wants nothing to do with an immanence of filth, seeking instead a pure transcendent realm of crystalline purity, reached only by cutting off all contact and gaining monadic isolation. The Upaniṣadic seer seeks to penetrate into the world; the hunger artist seeks to excrete it.

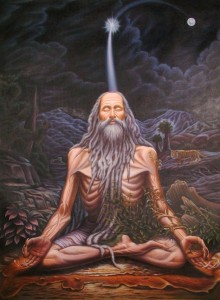

Isolation in the Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali

Similar processes of withdrawal are the primary techniques of classical yoga. Here we find the same metaphysical dualism, the same sensory and karmic materialism, the same emphasis on retention and restraint, and the same goal of kaivalya, isolation from the world. These processes are given detailed treatment in the Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali, perhaps to be dated to the second century CE: the sequence of the “eight limbs of yoga” given therein is one of progressive elimination of material interactions with the environment, the restricting of attention to an ever more narrow field of focus, and the final “breaking of the bridge” between the soul and the world by the removal of the contemplative object itself, leaving only pure interiority.

|

| The Yogi Attains Siddhi (artist unknown) Note the long fingernails and the vines growing over the body |

The five “outer limbs” of the process can be seen as a preliminary series of withdrawals of the body, the breath, and the senses from their habitual interchanges with the world. Patañjali here utilizes a threefold sequence of ever more subtle materiality to structure the process of physical retention. The first two limbs (yama and niyama: II.30-45) consist in moral rules and prohibitions; as in the Jaina texts, the erection of absolute ego-boundaries is built upon primary elimination of the mobility of body and semen in aggression and desire. Mobility ceases entirely in the third limb, posture (āsana: II.46), here defined as any stable — unmoving — mode of sitting: the body is restrained from its outward thrusting among the objects of the world. The practitioner is already preparing to be — as the Jaina texts put it — “motionless as a rock,” and as impenetrable.

The fourth limb carries the practitioner to the retention of more subtle matter: by control of the breath (prāṇāyāma: II.49-53) the practitioner “cuts off the motion of inhalation and exhalation.” The fifth limb (prātyāhāra: II.54) draws in the senses, which are of even finer material substance: the senses are here “disconnected from their objects,” and the physical organism is isolated entirely from the environment. The skin has now become the boundary of the self; the entire process has been one of guaranteeing the integrity of the integument. Flowing has been eliminated; as little as possible enters or leaves the gates of the soul.

The heart of the enstatic process, however, lies in the series of further exclusions that constitute the three “inner limbs,” which Patañjali collectively calls “restraint” (samyama): III.4). Here the mind — the most subtle substance of all — is first fixed upon a single object (dhāraṇā: III.1) until all awareness comes to a focus on that object alone (dhyāna: III.2). When nothing but that object appears in a contemplative state which is “as if empty of itself,” the practitioner has finally attained to concentration (samādhi: III.3). This sequence is one of progressive narrowing of the field of awareness to exclude everything outside of its single focus: everything else must be filtered out, even consciousness of the act itself. The state of awareness is thus “empty of itself,” for — says the commentator Vācaspatimiśra in the Tattvavaiśāradī — the mind no longer imposes its habitual distinction between itself and its object: there is only the unitary phenomenal object-awareness, a bare experience that floats alone within the ramparts of the skin.

This “concentration with object-awareness” (samprajñāta-samādhi) must still be refined, and the focus narrowed still further on its ever more subtle aspects. Patañjali gives two different lists of the types of this concentration: at I.17 he says that it may be endowed with vitarka, with vicāra, with ānanda, or with asmitā. At I.42-44 he says that it may either possess or lack vitarka and either possess or lack vicāra. Both lists of four represent a graded ascent from the first moment that the fluctuations of the mind have ceased in dhyāna (II.11); both lists specify that this ascent consists in the elimination of vitarka and vicāra.

These two terms recur in almost every Indian discussion of the process of enstasis: both are modes of mental interaction with an object, as either perceiving or identifying it. In the Tattvārthādhigama Sūtra (IX.43-44), the Jaina scholar Umāsvāti defines vitarka as “scriptural knowledge of the object” — an awareness of the object as canonically defined — and vicāra as a shift in focus or label or activity upon it. The Buddhist commentator Buddhaghosa, in Aṭṭhasālinī 114-115, says that vitarka is the initial singling out of the object, while vicāra is discursive work on it — “traversing” it and “threshing it out.” The former is like the thorn fixed in the middle in drawing a circle, and the latter is like the revolving thorn outside; or the former is like the hand that holds firm a dirty bowl, and the latter like the hand that scrubs the bowl with a brush; vitarka is coarse and vicāra subtle, like the initial striking of a bell and its subsequent reverberation.

|

| Patañjali, author of the Yoga Sūtra, in traditional form |

In the Yoga Sūtra, Patañjali differentiates the two mental processes in terms of the coarse or subtle materiality of their objects (I.42-47); his commentator Vyāsa distinguishes them in terms of the coarse or subtle quality of the experience itself (I.17). But no matter how subtle the object or the experience — reaching even an apprehension of the most subtle undifferentiated matter that underlies all other phenomena — the concentration is still a samprajñāta-samādhi, a “concentration with object-awareness,” a defiling interaction with the world. Both vitarka and vicāra are modes of eating — the commentators use the word ābhoga — which must be eliminated if the practitioner is to pass beyond the world. As even subtle contact with immanent materiality becomes attenuated, the experience becomes tinged with ānanda, “joy,” which grows with increasing distance from the pollution of matter, until even joy passes away in an overwhelming experience of asmitā, literally “I-am-ness,” the sheer existence of the separate soul.

Thus Vyāsa describes the progressive elimination of each of the four factors of concentration (I.17): “The first, concentration with vitarka, has all four; the second, without vitarka, has vicāra; the third, without vicāra, has ānanda; and the fourth, without that, has asmitā alone.” Joy and the sense of separate being must then be considered as products of the final clarity of the concentration without vicāra (I.47).

However read, the sequence is increasingly subtle in both object and experience. The movement is clear: the practitioner is moving through ever finer realms of matter, leaving behind the coarse polluting substance of the world, becoming filled with the joy of separation and the consciousness of the soul.

But the final bridge is yet to be broken: all experience is tainted with immanence. And so experience itself must come to an end. One eliminates even the awareness of one’s own translucent existence, and passes into the final enstasis of “concentration without object-awareness” (asamprajñāta-samādhi): here one casts aside all things of this world and abides empty of all awareness, without sensory content, without experience. All that remain are the seeds planted by one’s former actions (I.18), and when these are burned away one attains enstasis “without seed” for future experience (I.51).

These seeds are the last clinging traces of the world upon the soul: as they are consumed all bondage falls away, the primary energies of the world turn back upon themselves, mind and body dissolve, and the practitioner passes forever beyond. “This is the isolation of the soul,” says Vyāsa (III.55), “when it has its own light within itself, and is undefiled and alone.”

Isolation in the Tattvārthādhigama Sūtra of Umāsvāti

At just about the time that Patañjali was redacting a coherent structure from his mass of traditional material, the Jaina scholar Umāsvāti was summarizing his own tradition in the Tattvārthādhigama Sūtra, a work read even today in houses and temples of all segments of the Jaina community. Here the term dhyāna — “trance” — is used to refer to all the higher stages of progressive enstatic withdrawal (IX.27), the culmination of all the prior disciplines of suppression — defined as the “cessation of flow” (IX.1) — and destruction of deeds (IX.3). “Pure” trance is of four kinds: the first two are accessible to those on the eighth through the twelfth of the fourteen stages of the Jaina path, while the latter two can be attained only on the last two stages, by a kevalin or “solitary one” — a practitioner who has reached the goal of isolation and is about to cease all activity forever.

Despite minor differences in descriptive vocabulary, this sequence is structurally isomorphic with the process of “restraint” in Patañjali; it is hard to avoid concluding that both writers were drawing on very similar traditional sources. Thus the first trance state consists in vitarka and vicāra, Umāsvāti says (IX.39-43), and involves activity of body, speech, and mind together; the second trance state eliminates vicāra (IX.42), and is thus — given his definition of the terms — a state of awareness narrowed to a single aspect of the object, with no shift in focus or label, and involving activity only of body or speech or mind separately. The senses are now focused on the smallest possible point: there is no contact with the world save for this atomic center.

The practitioner is now on the eighth through the twelfth stage, depending on the amount of karma that has been destroyed. The one-pointed focus of the second trance starves the soul of its sensory input, and the inexorable wearing away of its accumulated defilement gradually frees it from ever more subtle attachments to the world. The twelfth stage is the summit of the ladder of destruction: the soul is still “enveloped” with the polluting vestiges of its past, but has now cut all affective links to matter: it remains on this stage for one antarmuhūrta (less than 48 minutes), then in the last instant becomes completely free of all hindering karma, and passes immediately into the thirteenth stage.

|

| The Jaina monk Muni Shri Maitri Prabh Sagar ji Maharaj on a fast unto death to protest a move to set up slaughterhouses in Uttar Pradesh |

The soul is now kevalin — “solitary” — and purged of its darkest and heaviest defilements: all that remains is the “non-hindering” karma that propels the soul into embodied existence until it reaches the term of life determined by its past. There is still the threefold activity of body, speech, and mind, but there is no new bondage: a deed is acquired in one moment, says the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra (XXIX.71), experienced in the second, and destroyed in the third. “Karma is produced, touches the soul, takes rise, is experienced, and is destroyed,” says the text. “For all time to come one is free of deeds.”

It is from this state that the soul prepares to enter the last stage of absolute motionlessness before departing completely from the world. Just as the “seeds” are burned and consumed in the final stages of “consciousness without object-awareness,” the practitioner here enters into the third trance (IX.39), which only now is the practitioner able to attain. All activity of speech and mind is stopped, and the coarse activity of the body: all that remains is the subtle activity of the body, the most basic physical life-processes. Once this trance is entered there is no turning back, for the process of emancipation continues automatically: immobility spreads as the links that connect the soul to he world are cut off one by one.

“First one stops the activity of one’s mind,” says the Uttarādhyāyaṇa Sūtra (XXIX.72), “then the activity of one’s speech, then that of one’s body, and at last one ceases to breathe.” The soul enters the fourteenth stage and the fourth trance state simultaneously: the subtle activity of the body ceases irrevocably, and the soul is steadily and impenetrably fixed within itself, “as motionless as a mountain rock.” All the remnants of karma are destroyed.

This stage of motionless solitude lasts only the length of time it would take to pronounce five short syllables; then the soul passes into disembodied isolation, flying upward to the end of the world, freed of the defilements that held it down. The soul gains transcendence, impelled by its own nature and its own momentum (X.5-7): the practitioner has passed forever beyond the world of filth and death.

Isolation in Buddhism

The one liberated by knowledge sees the world as it is with true knowledge. This discipline is the equivalent of Upaniṣadic “identification” — that is, applying the formulaic categories of doctrine to the events that pass before one. On the other hand, the bodily witness touches the immortal realm even in this life, attaining to the highest trance state wherein all thoughts and feelings cease. “Nirvana is happiness,” declares Sāriputta in Aṅguttara-nikāya IV.414. “But how can nirvana be happiness,” asks the foolish Udāyin, “when there are no feelings in nirvana?” “The happiness of nirvana,” Sāriputta replies, “is that there are no feelings in it.”

“Why does one enter this trance?” asks Buddhaghosa in his Visuddhimagga (XXIII.30). “One grows weary of the arising and ceasing of conditioned things, and thinks: Let me be without thought and dwell in bliss; here and now let me gain the cessation that is nirvana.” The Itivuttaka (46 and 63) and the Suttanipāta (754) praise the bodily witness of nirvana, preserving an enigmatic and archaic cosmology of material, nonmaterial, and cessation levels: beings who abide in the material and nonmaterial realms – the spheres of matter and mind, or of forms and names — return again to new becoming; only those liberated in cessation have escaped from death. The perfect Buddha has touched this immortal realm with his body, has experienced the casting aside of all clinging, has ceased all flowing. He proclaims the sorrowless and stainless way.

When a practitioner attains the highest trance state, we read in Majjhima-nikāya I.302, first the activity of speech is stopped: this is the cessation of vitarka and vicāra. Then the activity of body is stopped: this is the cessation of breathing. And then the activity of mind is stopped: this is the cessation of all thought and feeling. Majjhima-nikāya I.296 describes the difference between one in a trance and a corpse: the monk in a trance is still warm, his life continues, and his sensory organs are not destroyed but stilled; otherwise the corpse and the meditator are the same. The activities of body, speech, and mind have stopped in both.

Textual Archeology

It is clear, I think, that the literature in the various Buddhist canons that have come down to us reflect a relatively late state of the texts. Two assumptions can reasonably be made — first, that the texts circulating in the earliest Buddhist community were orally transmitted; and, second, that these oral texts themselves were made of older and shorter mnemonic texts that were elaborated and embedded in stories, metaphors, and commentaries.

When we try to reconstruct the earliest forms of Buddhist contemplative literature, therefore, we find what we can call contemplative pericopes — that is, brief, easily memorized meditative formulas, usually consisting of a series of sentences with third-person singular verbs, embedded in longer texts and combined in various ways with other literary elements. Two examples are given below of early Buddhist contemplative pericopes setting forth transcendent isolation as the soteriological goal — the *Vimokṣa Sūtra and the *Dhyāna Sūtra, where the initial asterisk indicates the reconstructed nature of the text.

The *Vimokṣa Sūtra

A very early formula for the attainment of this state of cessation – this sensory isolation and bodily impenetrability – is a list of eight “liberations” (Sanskrit vimokṣa, Pāli vimokkha). These are precisely the “nonmaterial states wherein matter is transcended” spoken of by Susīma in his questioning of the monks; they are in some texts (for example, Majjhima-nikāya I.478) the defining attainment of the “bodily witness.” The stereotyped formulation is found throughout the canonical literature (Dīgha-nikāya II.70, 111, III.261, 288; Majjhima-nikāya II.12; Aṅguttara-nikāya I.40, IV.306, 349); the Sanskrit text — found for example in the Mahāvyutpatti (1510-1518) and quoted in full by Yaśomitra in his commentary on Abhidharmakośa VIII.32 — is parallel to the Pāli version. It is clear that the text forms a separable mnemonic unit or contemplative pericope that we may name the *Vimokṣa Sūtra. It may be translated as follows:

(1) The material one sees matter.

(2) The one with no thought of internal matter sees external matter.

(3) One applies oneself, thinking, “It shines!”

(4) Completely transcending the thought of matter, all sensory response fading away, paying no heed to multiplicity, thinking “Space is infinite,” one enters and abides in the realm of infinite space.

(5) Completely transcending the realm of infinite space, thinking “Perception is infinite,” one enters and abides in the realm of infinite perception.

(6) Completely transcending the realm of infinite perception, thinking, “There is nothing at all,” one enters and abides in the realm of nothing-at-all.

(7) Completely transcending the realm of nothing-at-all, one enters and abides in the realm of neither thoughts nor non-thoughts.

(8) Completely transcending the realm of neither thoughts nor non-thoughts, one enters and abides in the cessation of all thought and feeling.

This formula is obscure, and was eventually superceded by other similar contemplative formulas, such as the sequences of the eightfold dhyāna (Pāli jhāna) discussed in the next section. The first through third of these eight liberations are archaic and unique to the *Vimokṣa Sūtra; four through eight are the four formless attainments, which appear also in the *Dhyāna Sūtra. Their authoritative age is guaranteed both by their inclusion in the canon and by the difficulties of later commentators, who attempted to homologize them to more familiar contemplative techniques.

|

| Buddhist monk meditating Phra Ajan Jerapunyo Abbot of Watkungtaphao (photo by Tevaprapas Makklay) |

The commentators agree, however, that the sequence is one of gradual transcendence of the material realm. Thus, for example, the Dhammasangaṇi splits the sequence into three sections — 1-3 (248-250), 4-7 (265-268), and 8 (not treated). This may be a late reflection of the earlier cosmology of the Itivuttaka and Suttanipāta: 1-3 = material realm, 4-7 = nonmaterial realm, 8 = cessation realm. The sequence may also reflect the ancient idea of karmic materialism, whose traces can be found scattered in the canon: Dīgha-nikāya III.230 and Aṅguttara-nikāya II.230 speak of light and dark deeds, and of the deeds — “neither light nor dark” — that bring about the destruction of deeds; Aṅguttara-nikāya III.284 speaks of practitioners who give birth to the nirvana that is neither light nor dark; almost the same words are found in Yoga Sūtra IV.7.

The same idea is revealed in enigmatic references to the natural purity and luminosity of the mind, which is stained by the defilements which come upon it (Aṅguttara-nikāya I.10; Mahāvibhāṣa T.1545 XXVII 731b11-12). We read in Suttanipāta 348 that the Buddha has removed these defilements as the wind drives away the dark clouds that cover the sun; this adventitious pollution or kleśa (Pāli kilesa) is etymologically related to the Jaina leśyā (Prakrit lesā), the “color” produced in the soul by the performance of deeds.

Scattered in the canon too are references to an archaic sequence of six elements (Dīgha-nikāya III.247; Majjhima-nikāya III.31, 62, 240; Samyutta-nikāya II.248; Aṅguttara-nikāya I.175), where earth, water, fire, air, space, and perception form a series of increasingly subtle material substances. The antiquity of the notion is evidenced by its incompatibility with the official theories of the Abhidharma (see, for example, Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośa I.28); a graduated scale of ever more subtle matter cannot be reconciled with the orthodox doctrine of the absolute otherness and individuality of the basic constituents of experience.

We thus find a vertical model of the cosmos, with the coarse and polluting matter at the bottom becoming finer and more attenuated — more shining and colorless —– as the practitioner ascends the stages of the trance. Three commentators seem to have preserved this sense of the sequence: Harivarman in the Satyasiddhi (T.1646 XXXII 339a16-340b16, a Bahuśrutīya text), Ghoṣaka in the Abhidharmāmṛta (T.1553 XXVIII 976a17-b16, a Sarvāstivāda text), and Asaṅga in the Abhidharmasamuccaya (T.1605 XXXI 690c23-691a22, a Vijñānavāda text). Here the practitioner progressively severs sensory contact with the material realm, “expels” matter from the self and thereby “destroys” the world, makes the world disappear by turning the mind from visible substance. The practitioner withdraws in trance first from the impurity of the body — “internal matter” — and then from that of the external world; the practitioner ascends through successive material levels to the infinite realms of the most subtle and pervasive elements. Here is where matter is attenuated and shining: the word śubha that characterizes the third liberation is elsewhere one of a series of quasi-synonyms used as stock epithets of a gem (Dīgha-nikāya I.76, 213; Majjhima-nikāya III.102): a jewel is said to be “shining, transparent, pure, unstained.” This is the shining transparency that one “witnesses with the body” when one is cleansed, internally and externally, from the material defilement that covers one.

This withdrawal from coarse matter seems to correspond to the state of “immobility” spoken of in Majjhima-nikāya II.253 and 262; Buddhaghosa, Papañcasūdanī IV.62, makes a similar identification: this anomalous state lies beyond the realm of desire: beyond immobility — beyond even the most subtle sensory substance — there is nothing-at-all. “Where do earth, water, fire, and air have no firm ground?” asks Dīgha-nikāya I.233. “Where do long and short, subtle and coarse, shining and unshining, where do name and form cease without a trace?” The Buddha answers: “Perception — invisible, infinite, everywhere radiant — is where earth, water, fire and air have no firm footing. Here long and short, subtle and coarse, shining and unshining, here name and form cease without a trace: here they cease with ceasing of perception.” Matter is attenuated to the breaking point: the practitioner enters an enstasis beyond form and name, beyond both the coarse unshining object and the subtler luminous sense: all matter is transcended with the transcending of perception. The same archaic schematization is reflected in Suttanipāta 1113: “He who has destroyed all thought of matter, who has cast aside all substance both within and without — he sees: Here is nothing.”

Beyond even the end of matter is the burning away of all awareness, all content, all experience: “It is calm and exalted,” says Majjhima-nikāya II.262, “when all thoughts cease without a trace.” Thoughts are a disease, an abscess, a dagger in the heart: “It is calm and exalted,” says Buddhaghosa in Visuddhimagga x.40, “to abide in neither thoughts nor non-thoughts.” And beyond this is the final cessation of all activity — identified with “perfect nirvana” at Majjhima-nikāya II.256 – and the motionlessness of body, speech, and mind: those who attain this purity and isolation — who are thus “well liberated” — are called kevalin or “solitary ones” at Samyutta-nikāya III.59. “There is nothing more to be known of them,” says the text. Suttanipāta 519 calls them unclinging, pure, concentrated, unmoving, alone: they have passed beyond the world.

The *Dhyāna Sūtra

In addition to the obscure and archaic *Vimokṣa Sūtra, we also find the well-known set of nine successive meditations (anupūrvavihāra) — for example, in Dīgha-nikāya III.265; Majjhima-nikāya I.40, III.25; Samyutta-nikāya II.210, 216, 221, III.235, IV.225, 2365, 263, V.10, 198, 213; Aṅguttara-nikāya IV.410, V.207. The last five items in this set are the same as the last five of the eight liberations — that is, the four formless attainments and the cessation of all thoughts and feelings. The first four items are the four trances (Sanskrit dhyāna, Pāli jhāna) of the realm of form, which are often found listed and discussed as a separate set (for example, Dīgha-nikāya I.37, 73, 172, II. 313, III.78, 131; Majjhima-nikāya I.21, 89, 117, II. 15, 226, III.4, 14, 36; Aṅguttara-nikāya I.53, 163, 182, II.26, 151, III.11, 119, and elsewhere). It is clear, however, that the complete set of nine meditations forms, like the *Vimokṣa Sūtra, a contemplative pericope which we can reconstruct and translate as follows:

(1) Separated from lust, separated from evil unclean states, one enters into and abides in the first trance, with vitarka, with vicāra, a state of joy and pleasure born from seclusion.

(2) Suppressing vitarka and vicāra, one enters into and abides in the second trance, a state of joy and pleasure, born from concentration, mind focused, composed within, without vitarka, without vicāra.

(3) Putting aside joy, one abides with equanimity, one enters and abides in the third trance, mindful and composed, one’s body pervaded by that pleasure of which the Noble Ones say, “One of equanimity and mindfulness abides in pleasure.”

(4) Putting away pleasure and pain, one enters and abides in the fourth trance, with prior delight and despair passed away, without pleasure, without pain, a state of pure equanimity and mindfulness.

(5) Completely transcending the thought of matter, all sensory response fading away, paying no heed to multiplicity, thinking “Space is infinite,” one enters and abides in the realm of infinite space.

(6) Completely transcending the realm of infinite space, thinking “Perception is infinite,” one enters and abides in the realm of infinite perception.

(7) Completely transcending the realm of infinite perception, thinking, “There is nothing at all,” one enters and abides in the realm of nothing-at-all.

(8) Completely transcending the realm of nothing-at-all, one enters and abides in the realm of neither thoughts nor non-thoughts.

(9) Completely transcending the realm of neither thoughts nor non-thoughts, one enters and abides in the cessation of all thought and feeling.

In Dīgha-nikāya III.265-266 and Aṅguttara-nikāya IV.410-414, we are told that the nine trances are acquired by nine successive cessations (nirodha) which eliminate, in sequence, desire, vitarka and vicāra, enthusiasm, breathing, the thought of matter, the thought of the infinity of space, the thought of the infinity of perception, the thought of nothing-at-all, the thought of neither thoughts nor non-thoughts, and finally all thoughts and feelings. Vasubandu’s Abhidharmakośa (VIII.2) similarly states that the first trance possesses vitarka, vicāra, enthusiasm, and pleasure; the second discards vitarka and vicāra; the third discards enthusiasm; and the fourth discards pleasure.

It is this nine-fold formulation — rather than the archaic *Vimokṣa Sūtra — that became the standard contemplative sequence, elaborated in such encyclopedic sources as Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośa and Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga. Yet the similarities are striking not only with the *Vimokṣa Sūtra — a progression from coarse interactions with coarse material substances through ever more rarified, pure, undefiled, and crystalline realms to liberation — but with the yogic and Jaina paths as well.

Trance Tales

The silence and immobility of this state of sensory withdrawal were a motif in Buddhist folklore. The Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā commentary to the Dhammapada (II.254), attributed — probably incorrectly — to Buddhaghosa, tells the story of the monk Kondañña, who is so absorbed in trance that a band of five hundred thieves, returning in the dark from plundering a village, take him to be a tree stump. One of the thieves puts his sack of loot on the monk’s head, and the rest pile their sacks about him. At dawn they collect their sacks; they see the monk and, thinking he is an evil spirit, start to run away. He calls them back, and they are so impressed that they become his disciples. From that day forward he is known as Khāṇu Kondañña – Kondañña the stump.

In the Udāna (39) we read of the venerable Sāriputta sitting in trance in the moonlight just after having his head freshly shaved. Two wicked spirits see him, and one — obviously tempted by his bald and shining pate — says to the other, “It occurs to me to give this wanderer a blow on the head.” His companion attempts to dissuade him, but he persists, and finally he gives Sāriputta such a blow on the head as might have felled an elephant or split a mountain peak. Immediately the spirit falls blazing into hell, screaming “I burn! I burn!” Sāriputta notices nothing: he emerges from his trance with a slight headache.

In the Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā (II.247) a novice monk, to save the others of his community, offers himself to a band of thieves who wish to make a human sacrifice to a local deity. The novice enters into trance as the thieves sharpen the stake and prepare the fire; their leader strikes him with his sword, but at the first blow the weapon bends, and at the second blow it splits from hilt to tip like a palm leaf. Again, the Majjhima-nikāya (I.334) tells of Sañjīva the forest dweller, who enters into the trance wherein all thoughts and feelings cease. Some cowherds and farmers come across him at the foot of a tree and, thinking that he is sitting there dead, decide to cremate him. They pile grass and sticks and cowdung on him, set it on fire, and leave; Sañjīva remains in the trance until morning, then arises, shakes his robes, and walks to the village for alms.

Conclusion

There is a archaic pan-Indian soteriological tradition — influencing Buddhism, yoga, and Jainism — that sees salvation as transcendent immobility and isolation from a filthy and polluting world. In this tradition, the cosmos is vertically aligned, with gross and heavy matter on the bottom and more subtle and luminous matter as one ascends. The goal is to purge oneself — through the cessation of flow — of all matter, to separate the inherently isolated and monadic self from the polluting universe, and finally to achieve a state of static and eternal isolation from all thoughts, feelings, and experiences, all of which are seen as being, in some sense, material.

This radically dualistic tradition contrasts markedly with the tradition of Upaniṣadic insight and identification, which also influenced Buddhism, and allegedly culminated in the version of advaita Vedānta popularized in the west by Hindu intellectuals such as Swāmī Vivekānanda and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan. The latter tradition, through processes of colonizing discourse, has been taken as normative not only for Hinduism but for all religions, and enshrined in popular culture by Aldous Huxley, Huston Smith, Ken Wilber, and others in the form of the Perennial Philosophy. However, the soteriological claims of transcendent isolation are inconsistent with claims of perennialism, and challenge current cartographies of consciousness.

REFERENCES

1. Primary sources

1.1 Buddhist texts

1.1.1 Pāli texts

1.1.1.1 Canonical texts

Aṅguttara-nikāya. R. Morris, ed. (1885/1961/1989). Vol. 1; R. Morris, ed. (1888/1976/1995). Vol. II; E. Hardy; ed. (1897/1976/1994). Vol. III; E. Hardy; ed. (1899/1979). Vol. IV; E. Hardy; ed. (1900/1979). Vol. V; M. Hunt & C.A.F. Rhys Davids (1910/1981).Vol. VI, Indexes. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1960). Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as The Book of the Gradual Sayings. F.L. Woodward, trans. (1932/1989/1995). Vol. I; F.L. Woodward, trans. (1933/1992/1995). Vol. II; E.M. Hare, trans. (1934/1988/1995). Vol. III; E.M. Hare, trans. (1935/1989/1995). Vol. IV; F.L. Woodward, trans. (1936/1994). Vol. V. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Dhammasangaṇi. E. Müller, ed. (1885/1978). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1960). Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as Buddhist Psychological Ethics. C.A.F. Rhys Davids, trans. (1900/1993). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Dīgha-nikāya. T.W. Rhys Davids & J.E. Carpenter, eds. (1889/1983/1995). Vol. I; T.W. Rhys Davids & J.E. Carpenter, eds. (1903/1982/1995). Vol. II; J.E. Carpenter, ed. (1910/1992). Vol. III. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1958). Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as Dialogues of the Buddha. T.W. Rhys Davids, trans. (1899/1973/1995). Vol. I; T.W. Rhys Davids & C.A.F. Rhys Davids, trans. (1910/ 1989/1995). Vol. II; C.A.F. Rhys Davids, trans. (1921/1991/1995), Vol. III. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Itivuttaka. E. Windisch, ed. (1889/1975). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also in Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1959). Khuddaka-nikāya. Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as As It Was Said. In F.L. Woodward, trans. (1935/1985). Minor Anthologies, Vol. II. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also translated as The Sayings of Buddha. J.H. Moore, trans. (1908). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Majjhima-nikāya. V. Trenckner, ed. (1888/1993). Vol. I; R. Chalmers,, ed. (1896-98/1993). Vol. II; R. Chalmers, ed. (1899-1902/1977/1994). Vol. III; C.A.F. Rhys Davids (1925/1991). Vol. IV, Indexes. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1958). Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as Middle Length Sayings. I.B. Horner, trans. (1954/1993/1995). Vol. I; I.B. Horner, trans. 1957/1989/1994). Vol. II; ; I.B. Horner, trans. (1959/1993). Vol. III. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Samyutta-nikāya. L. Feer, ed. (1884), G.A. Somaratne, ed. (1999). Vol. I; L. Feer, ed. (1888/1989/1994). Vol. II; L. Feer, ed. (1890/1975). Vol. III. L. Feer, ed. (1894/1990). Vol. IV; L. Feer, ed. (1898/1976). Vol. V; C.A.F. Rhys Davids (1904/1980). Vol. VI, Indexes. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1959). Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as The Book of the Kindred Sayings. C.A.F. Rhys Davids, trans. (1917/1993). Vol. I; C.A.F. Rhys Davids (1922/1990). Vol. II; F.L. Woodward, trans. (1924/1992/1995). Vol. III; F.L. Woodward, trans. (1927/1993). Vol. IV; F.L. Woodward, trans. (1930/1994). Vol. V. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Suttanipāta. D. Andersen & H. Smith, eds. (1913/1990). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; L. Chalmers, ed. (1932). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; also in Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1959). Khuddaka-nikāya. Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as The Group of Discourses. K.R. Norman, trans. (1992/1995). Vol. II. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also L. Chalmers, trans. (1932). Buddha’s Teachings, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Udāna. P. Steinthal, ed. (1885/1982). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also in Bhikkhu J. Kashyap, gen. ed. (1959). Khuddaka-nikāya. Bihar, India: Pāli Publication Board. Translated as Verses of Uplift. In F.L. Woodward, trans. (1935/1985). Minor Anthologies, Vol. II. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society; also P. Masefield, trans. (1994). The Udāna. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

1.1.1.2 Non-canonical texts

Buddhaghosa, Aṭṭhasālinī (commentary on the Dhammasangaṇi). E. Müller, ed. (1897), L.S. Cousins, rev. (1979). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society. Translated as The Expositor. Pe Maung Tin, trans. (1920-1921/1976). Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society.

Buddaghosa, Dhammapadaṭṭhakathā (commentary on the Dhammapada). H.C. Norman, ed. (1906-1909/1993). Vol. I; H.C. Norman, ed. (1911, 1993). Vol. II; H.C. Norman, ed. (1912/1993). Vol. III; H.C. Norman, ed. (1914/1970). Vol. IV; L.S. Tailang, ed. (1915/1992). Vol. V, Indexes. Oxford, UK: The Pali Text Society. Translated as Buddhist Legends. E.W. Burlingame, trans. (1921/1990). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.