The study

|

| José Carlos Bouso |

Clinical psychologist José Carlos Bouso of the Human Experimental Neuropsychopharmacology group in Barcelona, in collaboration with researchers from several Spanish and Brazilian research centers, has published a new epidemiological study of long-term frequent users of ayahuasca in two Brazilian churches. This study expands upon previous work in four important ways.

- First, the study examined a much larger cohort of subjects and controls than any previous study. The well known and often cited 1996 study of the União do Vegetal by Charles Grob and his colleagues examined fifteen long-term urban ayahuasca users and fifteen controls matched for age, ethnicity, marital status, and level of education. The 2008 study of members of an American Santo Daime church by John Halpern and his colleagues examined 32 ayahuasca users and no matched controls. In contrast, the current study enrolled and tested 127 ayahuasca users and 115 controls matched for age, sex, and years of education.

- Second, the current study enrolled and tested members of two different Brazilian ayahuasca churches — the Centro Eclético de Fluente Luz Universal Raimundo Irineu Serra, a branch of the Santo Daime church, and Barquinha, neither of which had been studied before in their Brazilian context. This choice additionally allowed the study to compare a rural cohort, the CEFLURIS community at Céu do Mapiá in the Brazilian State of Amazonas, with an urban one, the Barquinha community in the city of Rio Branco, the capital of the State of Acre.

- Third, unlike previous work, the current study followed up after one year by retesting all available participants. There was, as expected, some drop-out: in total, 49 ayahuasca-using subjects and 47 controls were lost to follow-up. No statistically significant differences were noted on subsequent testing.

- Fourth, the current study expanded upon the body of tests which have been administered to ayahuasca-using church members, utilizing a very wide range of personality, psychopathology, life attitude, and neuropsychological performance measures, which differed from the instruments used in previous studies.

The findings

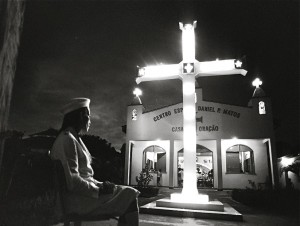

|

| Centro Espirita Daniel Pereira de Matos, a Barquinha center in Rio Branco (photo by Luis Veiga) |

So what did the study find? Ayahuasca users were found to measure significantly lower than the controls on all nine psychopathology scales, including significantly less somatization, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and phobias. The ayahuasca users scored significantly lower than controls on measures of worry, shyness, and fatigability and weakness. And ayahuasca users scored significantly higher than controls on measures of self-transcendence and spiritual orientation, including on such items as transpersonal identification, self-forgetfulness, sacredness of life, altruism, subjective well-being, and mission in life. “Taken together,” the authors state, “the data point at better general mental health and bio-psycho-social adaptation in the ayahuasca-using group compared to the control subjects.”

The authors conclude:

The assessment of the impact of long-term ayahuasca use on mental health from various perspectives (personality, psychopathology, neuropsychology, life attitudes and psychosocial well-being) did not find evidence of pathological alterations in any of the spheres studied. Although ayahuasca-using subjects differed in some personality traits, differences did not fit with a pathological profile. Furthermore, ayahuasca users showed a lower presence of psychopathological symptoms compared to controls. They performed better in neuropsychological tests, scored higher in spirituality and showed better psychosocial adaptation as reflected by some attitudinal traits such as Purpose in Life and Subjective Well-Being. Overall differences with the control group were still observable at follow-up one year later.

The findings here are consistent with those of the two earlier epidemiological studies. This study thus adds weight to the claim that no evidence has yet been found of psychological maladjustment, mental health deterioration, or cognitive impairment in human adults who ingest ayahuasca regularly, frequently, and over long periods of time as committed members of the Brazilian ayahuasca churches.

Two cautions about interpretation

But two cautions apply to any interpretation of such claims. First, we must be very cautious in attempting to generalize the results of this study — or either of the two earlier studies — outside the specific cultural and institutional settings in which the studies were carried out.

|

| Welcome to Céu do Mapiá, the CEFLURIS community in Amazonas |

And, second, we must be very cautious in drawing from this study any inference that drinking ayahuasca is somehow the cause of the lower psychopathology and higher spirituality scores of the ayahuasca church members as compared to the controls. Such a conclusion would be subject to a form of error called selection bias.

Here is how selection bias works. In order to be enrolled in the study, all of the ayahuasca-using subjects had to have been taking ayahuasca at least twice a month for a minimum of fifteen years — that is, to have been conscientious, consistent, and meticulous in their church attendance over a long period of time. Such subjects were therefore selected for such personality traits as orderliness, compliance, and socialization into church values.

On the other hand, the controls are described simply as followers of traditional Christian religions, either Protestant or Catholic, apparently by self-description. While the authors state that the majority of individuals in the comparison groups were actively practicing their religion, we are not told what that practice required in terms of, say, frequency or duration of church attendance. The ideal control group would have been matched for long-term and highly regular churchgoing in a non-ayahuasca church. To the extent that the ideal is not achieved — or is unachievable — the underlying personality traits remain an uncontrolled variable.

There is in fact evidence for this differential in the test scores. The subject members of the ayahuasca churches scored significantly higher than the controls on measures of attachment and dependence, and significantly lower than the controls on measures of responsibility, purposefulness, resourcefulness, and self-acceptance. This creates a picture of participants who have been well integrated into a relatively rigid institutional structure — just as we would expect of people who attend religious ceremonies at least twice a week for more than fifteen years. The disorderly, the noncompliant, the depressed, the anxious, and the disturbed were excluded from the ayahuasca-using cohort by virtue of the enrollment criteria.

|

| Oração in the CEFLURIS church |

In addition, the ayahuasca-using subjects were selected for having had no serious early physical or mental problems with ayahuasca, or having had no problems with conforming to the often restrictive behavioral rules and institutional strictures of the church. Presumably persons who attended either of the churches, tried ayahuasca, and had an adverse reaction, or found the church rules uncongenial, would then likely have stopped attending, and would not have been included in the ayahuasca-using cohort.

It is probably worth pointing out that this bias is not a conceptual defect in the study design, but rather appears to be inevitable in the study of long-term ayahuasca use in any of the settings in which it is likely to be found. The same selection bias would affect a study, say, of elder ayahuasca shamans in the Upper Amazon.

And it is also important to point out that the neuropsychological tests — the Stroop Color and Word Test, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, Letter-Numbering Sequencing, and the Frontal Systems Behavior Scales — are independently normed. On all of these tests, the study “found no evidence of neuropsychological impairment in the ayahuasca using group,” which I take as meaning that the ayahuasca-using subjects all fell within the normal range for those tests. Since the tests are independently normed, there would be no selection bias in the results, which indicate that fifteen years of regular, frequent ceremonial use of ayahuasca is not associated with any deterioration in cognitive function.

There is an additional consideration. The study demonstrates an apparent association between drinking ayahuasca and significantly higher scores than controls on measures related to spirituality. But the data do not allow us to tell in which direction this association runs. Perhaps these higher scores are the result of drinking ayahuasca; or, instead, perhaps those who scored high on these measures were preferentially attracted to the ayahuasca churches, as opposed to other more traditional congregations. The data simply do not allow us to say.

|

| A Barquinha healing ritual |

The same is true for the psychopathology scores. The study shows an apparent association between ayahuasca consumption and lower scores on measures of psychopathology. The study cannot tell us if there is a causal connection, or, if there is, in which direction it runs. It may be, for example, not that long-term ayahuasca drinking causes better mental health, but rather that people with better mental health are more likely to drink ayahuasca long term, or even that some third factor — socioeconomic status, for example, or deeply held spiritual beliefs, or particular institutional environments — is causally related to both.

Conclusion

But none of this detracts from the study itself, or from the inferences that can legitimately be drawn from it. Leaving aside the informal but informative study of ayahuasca and psychopathology among the Shuar that I discuss here, we now have three different epidemiological studies that have looked at a total of 184 long-term adult ayahuasca users, both Brazilian and American, utilizing a wide variety of psychological and neuropsychological test instruments. All studies agree in reporting no finding of psychological or neurological harm from frequent long-term ceremonial ayahuasca use by committed adult members of the Brazilian ayahuasca churches.

- Previous Post: Vodka, Ayahuasca, Found Footage

- Next Post: A Peyote Joke

- More Articles Related to: Ayahuasca, Research Studies

So let´s see the old shamans who have taking the medicine for many years.

They are ok, they are lucid.

Dear Stephan,

Thank you very much for your extensive report regarding our study. I liked it very much. I just would like to do few observations:

You are true here, this is the reason why we say in the discussion section that it would be very interesting to assess subjects that to start drinking ayahuasca but for whatever reason they drop out. And this is also valid for psychopathology, since we know of several cases of psychotic breakdowns after taking ayahuasca.

You are true here also but sometimes the “critics” :) do not have in mind the difficulties in recruiting volunteers for such a studies. Becouse of this possible bias, is why in our paper we do not interpret the data a differences between ayahuasca users and non users, but in terms of how those concrete personality traits may explain their adherence to a doctrine in some different ecological enviormentals where a powerful drug is ingested. In particular, we discuss the difference between the urban and jungle groups: how, by expample for the jungle group, some concrete character traits may serve to explain their adaptation to some hostile enviorments. We were very caoutios in to interpret diffrerences between controls and ayahuasca users caused by ayahuasca and we tried to use the personality tests to better understand their adherence to the doctrine. We also especulate if those personality traits may be a previous condition to ayahuasca use or a consequence.

Reading your critic, I am thinking that maybe we should use the SOI (Spiritual Orientation Inventary) as a match variable and not as a comparison one. I think that this approach would be more useful that counting the years of religion practice in ordeer to match groups. But this approach is almost impossible in terms of time and money consuming if you want to assess a such large sample as we did.

Anyway, our idea was not to do an ayahuasca study, but a study regarding long terme effects of a psychedelics. That’s the reason why we choose people that was taking ayahuasca for at least 15 years. Becasue their use of other drugs was minimal compared with studies were arfe assessed ecstasy or whatever other drug. If after 15 years the general mental health (psychopathology, neuropsychology and personality and attitude traits) are ok, we can conclude that ayahuasca is not neurotoxic. It may cause psychosis and mental health problems in certain people, but not as a cause of a brain damage but for whatever other reasons. Our objective, at last, was to have indicators of brain damage.

Nowdays there is a tendency to administer subjects a large battery of neuropsychological tests in order to study possible neuropsychological defficits. For several reasons I think that this is not a good strategy, so we choose the other less statistically biased option: few tests assessing diffrent things. SInce our ayahuasca subjects did not show alterations in personality, neuropsychology, etc., is becouse we conclude that ayahuasca was not harmful for them. In that way, to have a control group serves to assure that. Our intention was not finding differences in personality or whatever between users and not users, but to assess long term safety.

Anyway, our results are impressive since religios practices may cause brain damage:

http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0017006

(this is a joke)

I don’t know if you ever went to Mapia, but CEFLURIS is not a paradigm of a “relativity rigid institutional structure” (by the way, I’ve never been there becouse I wanted to interpret our data with the most possible objetivity, so I do not know anything at all in person about any of our study subjects nor our study groups). But I think that they are the opossite to the UDV. Anyway, our principal bias was that, effectivelly, maybe the sample is a self-selected sample, as we discuss in the paper. This is aproblem in every neuropsychological study. By example, lots of papers about cocaine use has the same problem, but at the contrary: since they select people from treatment centers there is also a self-selection bias to the worst functioning.

Again, that is becouse the dificulty to find people that start using ayauasca but sttoped its use. I am very interested in doing that kind of research, but the sample is a very hiden one, and is very difficult to reach them. Anyway, now that I am working for ICEERS this is one of our future objectives.

This is the key to use a control group: you not need to have the tests normed since you have a control group matched in variables that may influence neuropsychological performance. And that the reason why we wanted to study people that was 15 years taking ayhuasca. If ayahuasca is neurotoxic, doesn’t mind if it is used in the context of a ritual or not. If is toxic for the brain is toxic for the brain. Here is very important to use a control group. We could not matched subjects by CI, becouse reasons of time (to aseess so meny people -more than 200- was a titanic work. We have data with neuroimaging and more sophisticated neuropsychological tests from Spanish ayahuasca users matched by CI with controls. But the sample is smaller). It is not aeasy to develope this kind of studies and is inevitable to have always some kind of bias. Anyway, our large sample I think that reduce the interpretation problems, since a sample of 100 subjects statistically is considerer normal sample.

You are true. this kind of studies can not stay in wich directions go the rersults, only speculate about it. to speculate about casuality you need a clinical study, the one that are developed in animal research were you have animals in jails since they are born and so on. fortunatelly, this kind of research that may reach casuality results is not possible to do it today:)

Again, we discuss that issue largery in our paper. so there are neeed studies assessing people that start to take ayahuasca and stop it. as i am saying, our main objective was to assess if ayahuasca may be neurotoxic. when somebody suffer of neurotoxicity, diffrent areas are affected: behaviors, personality, psychopathology, cognitive functions, since all that areas are areas that are influenced by brain functioning. our study trend to conclude that ayahuasca is not neurotoxic. it may cause other problems that should be researcher, but if it was neurotoxic all those people should have worst functioning in all the areas assessed than their controls. Anyway, we are analyzing our neuroimagin studies in order to look for some kind (or not) of more subtle brain damage (or benefit).

Thank you again for your comment of our study in your blog.

Best wishes,

José Carlos.