Peruvian cuisine got a lot of good news this month. Irzio Pinasco, chairman of the Economic Committee of the Peruvian Gastronomy Association, announced that the Peruvian gastronomy sector will generate 320,000 jobs this year, with about 240,000 of them in Lima. In recent years, he said, the number of restaurants grew 45 percent nationwide.

|

And Spanish chef Borja Blásquez, academic director of the Gastronomic Institute of Argentina, whose program on the El Gourmet cable TV channel is very popular in Latin America, told reporters in Arequipa that Peruvian dishes were “incomparable” — “the best in Latin America,” he said. “Peruvian cuisine’s fusions, and very especially its historic roots, are valuable things that can hardly be equaled by any other cuisine from this part of the continent.”

Fusion is the hot word among Peruvian chefs. Pedro Miguel Schiaffino — see biographies here and here — was one of the founders of what is now generally called Amazon fusion, which incorporates jungle ingredients into gourmet dishes. Schiaffino — the “young promise of Peruvian gastronomy” — studied at the Culinary Institute of America and at the Italian Culinary Institute, and he got practical kitchen experience under chefs Nadia Santini and Piero Bertinotti in Rome. Upon his return to Peru, he took charge of the kitchen at La Huaca Pucllana in Lima, creating what came to be called neoandina or nouveux Andean cuisine, and then opened the restaurant Malabar in Lima with the idea of offering a new fusion cuisine using jungle ingredients.

Back in May, the first Festival Gastronómico de la Amazonía peruana was held for five days at the Hotel Meliá in Lima. I missed it. I had intended to bring some genuine Amazonian boiled monkey soup, but, as it turns out, it is likely the festival would not have been interested.

|

The event was sponsored by PromPerú — the Comisión del Promoción del Perú para la Exportación y el Turismo — and was attended by several Peruvian dignitaries, including Mercedes Aráoz, the Minister of Foreign Trade, and Antonio Brack, Minister of the Environment.

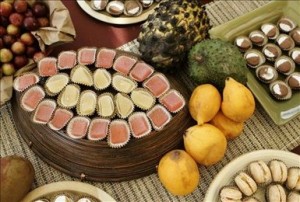

The big hit of the show was Amazonian fruit — ubos, sapote, anona, camu-camu, guanábana, conoca, aguaje, guayaba. In addition to the fruit, there was yuca, of course, and fish — I wrote about Amazonian fish here — and meat of wild pig and deer. As far as I can tell they served no large rodents, such as capybara or agouti, both widely eaten in the Amazon, and no monkey or spiny rats. I do not know whether they served suri, the grubs of palm beetles, considered a special treat in the Amazon.

In other words, when people in Lima speak of Amazonian gastronomy, they do not mean what indigenous people in the Amazon actually eat. They mean European preparations of Amazonian ingredients as similar as possible to those already used in Eurpoean gastronomy.

In the same way, one press release speaks of the jungle fruits on display as having been produced with “only minimal traditional management,” as if the fruit had just magically appeared out of the jungle, ignoring the fact that both mestizo and indigenous Amazonian peoples are active and ecologically astute forest managers.

Although the coverage is sketchy, there seem to have been no actual indigenous Amazonians present, except as dancers, for entertainment. All the headline chefs had restaurants in Lima, and all of them had been trained in Europe.

|

One product of the festival was a new forty-recipe cookbook, with scrumptious photographs, entitled Frutas amazónicas, postres peruanos de vanguardia, written by chef Astrid Gutsche.

Gutsche, born in Germany, manages the restaurant franchise Astrid & Gastón along with her husband, Peruvian chef Gastón Acurio Jaramillo. They met at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris and have opened a number of restaurants in Lima specializing in Peruvian seafood, Peruvian confections, and — their latest — Peruvian sánguches, sandwiches.

The desert book was originally the idea of photographer Walter Wust, who solicited the support of the Proyecto Perúbiodiverso of PromPerú, which hoped that the book would help to promote the the use and export of Amazonian fruit. The promotional material for the book speaks sensually of a “host of revolutionary desserts, unexpected flavors, and exotic drinks. The bright yellow of cocona, the promising camu camu, the delicate aguaje, the creamy shimbillo, among many others, open up a range of textures and colors that provide infinite combinations. Under its green cloak of secrecy, the jungle hides sweet pleasure.”

This is the jungle in the Peruvian imagination — erotic, seductive, its unmanaged treasures waiting to be extracted.

- Previous Post: Metamorphosis

- Next Post: The Collective Unconscious

- More Articles Related to: Books and Art, Indigenous Culture, The Amazon

I really enjoyed sampling the indigenous cuisine while in Peru. Sadly I don’t remember the names of anything, haha. There was a fruit, a small red fruit that you peeled to reveal a yellow/orange inside. It was not sweet at all but very rich and tasty with a sprinkle of salt. I also enjoyed eating the “lemon ants”. It was weird to consciously stick a live ant in your mouth but once you crunched them you got a mouthful of lemony flavor not at all different from lemon zest. It was also interesting to see the Amazon’s take on gringo food. I really enjoyed Ari’s Burger in Iquitos. They had a vegetable sandwich that included to my surprise, beets. Not to mention they probably have the best ice cream I have ever tasted in my entire life. On the packaged side, I LOVED Choko Soda, little saltine crackers with an outer coating of chocolate. I cannot wait to get my hands on some more of those. Ok, that one isn’t really Amazonian but it was too good not to mention!