On March 25, 1916, a man of unknown name died of tuberculosis in California. He was known as Ishi, but that was not his real name, which no one knows; the word ishi means man in the Yahi language.

Ishi was the last surviving Yahi. His people had been destroyed by mining silt that poisoned their salmon streams, livestock that competed for grazing with deer, epidemics of alien diseases. His people had been hunted down and killed by white ranchers.

In the early 1860s, the Yahi started to steal cattle in order to survive. The cattle ranchers responded by slaughtering Yahi, who were apparently less important than cows. The Three Knolls Massacre in 1865 left only thirty members of the people alive. The ranchers used dogs to find the survivors, and killed another fifteen. The remainder fled into the hills, where they hid for more than forty years. By 1911, the man known as Ishi was the only one left. The whole story is here.

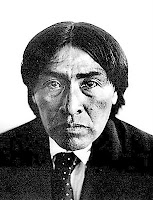

|

| Ishi |

Ishi was caught, apparently trying to steal food, in Oroville, California, and came to the attention of two anthropologists, Alfred Kroeber and Thomas Waterman, who arranged for him to live at the new University of California museum of anthropology in San Francisco. Ishi survived by working as an assistant at the museum, demonstrating the living skills of the Yahi, identifying the Yahi artifacts that had been taken from his people. Spectators paid money to see him make arrowheads.

Kroeber’s wife, Theodora, later wrote two popular books about Ishi, which are still in print. Their daughter, Ursula Le Guin, is a respected science fiction writer, whose work constitutes a sort of speculative anthropology of culture contact. In her novel Always Coming Home, for example, she describes the culture of the Kesh, inhabitants of the Napa Valley in California long after some unnamed catastrophe has sunk the cities of the coast. The book is a collage of autobiography, verse, tales, reports, drawings, music, and even the recipes of a minutely constructed egalitarian matriarchal culture that had — much like Ishi — survived contact with a group of hierarchical and murderous outsiders.

When Ishi died, the museum staff apparently tried to give him a traditional Yahi funeral. They cremated him along with bow and arrows, acorn meal, shell beads, tobacco, jewelry, and obsidian flakes.

But there was one last Yahi artifact to be plundered. Someone took Ishi’s brain, presumably so that it might be studied someday, like a Yahi basket. The brain then disappeared.

Under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a group of Maidu Indians from the Sierra Nevada region sought to reclaim Ishi’s ashes and bury them in his tribal homeland near Mt. Lassen. Duke University anthropologist Orin Starn helped them — finally — locate the missing brain in an obscure Smithsonian storeroom. Starn has written a poignant and outraged book about his quest.

Today is the anniversary of the death by tuberculosis of a man with a name no white person ever knew. He has gone to join his people.

- Previous Post: Handling Infections

- Next Post: Eagle Feathers

- More Articles Related to: Indigenous Culture

I worked at a wolf sanctuary for a while, and cared for a very old wolf named Ishi. I knew the story of his name was compelling and horrifying, but never looked into it. It’s good to know the tale now. Wolf Ishi’s tale ended much more kindly…may they both rest peacefully.

I believe that the universe is a non-zero-sum game, and that one of our purposes on this planet is to increase as much as we can the sum total of happiness in the universe. By caring for Wolf Ishi you have increased the level of happiness in the universe by a quantum of wolf joy and a further quantum of human caring. I am sure the universe — in its own odd way — is grateful. I know I am.