I mentioned here that the temperature in the jungle remains pretty steady at around 85 degrees and the relative humidity at about 90 percent. Although the temperature in the jungle does not get as high as it does in the desert, the high humidity prevents the rapid evaporation of sweat, which is one of the body’s primary cooling mechanisms. You can be perfectly comfortable under most jungle conditions, but you can still get heat illness if you are not careful.

Heat illness or hyperthermia is what happens when you are too hot. There are two serious types of hyperthermia — heat exhaustion and heat stroke. The two conditions are points on a continuum which runs from being uncomfortably hot to being deathly ill. The primary difference between heat exhaustion and heat stroke is that in heat exhaustion the body’s heat dissipating mechanism has been overworked, while in heat stroke the body’s heat dissipating mechanism has been overwhelmed.

It is important to remember that, in the jungle setting, both heat exhaustion and heat stroke can often be prevented simply by adequate hydration. Whoever designed the human body made two major mistakes — the knee, which comes apart under even moderate lateral pressure, and the thirst mechanism. The trigger for thirst is a beginning electrolyte balance; that is, when you get thirsty, it is already too late. That is why it is important to drink lots of water in the jungle, and to drink it before you get thirsty. Pound it down. Force yourself. Drop a tea bag in your water bottle to give the water some taste. Set up a rule that if one person drinks, everyone has to drink.

How much should you be drinking? Under normal circumstances, water intake should be between 9 and 12 cups per day — that is, between about 2¼ and 3 quarts of water per day. The amount needed can increase with exercise and environmental factors. In 2003, the International Marathon Medical Directors Association and USA Track and Field jointly issued fluid replacement guidelines for marathon runners, advising them to drink as much as they wanted between 400 and 800 mL/hour — that is, between 0.42 and 0.84 quarts each hour. For an average amateur marathoner, that means between about two and four quarts during a five-hour marathon. Conversely, with only light to moderate exercise, a person in the desert should drink about four quarts of water per day.

But you don’t have to measure your intake when you can observe your output. You can know you are properly hydrated by paying attention to your urine. Your urine should be clear, copious, and colorless — or at least pale yellow. Most people live in a state of chronic dehydration; so, when you are properly hydrated, you should feel like you are urinating a lot.

|

| Heat exhaustion |

Since the brain is one of the first organs affected by inadequate perfusion, one of the first signs of heat exhaustion is often a change in level of consciousness — spaciness, forgetfulness, confusion, odd speech, restlessness, anxiety, and changes in behavior, sometimes subtle. Other signs and symptoms are thirst, weakness, headache, nausea, dizziness, rapid pulse, rapid breathing, exhaustion, and profuse sweating. Patients can sweat so much that they feel cold, have goose bumps, and complain of chills. The skin is cool and pale.

The treatment for heat exhaustion is simple. Get the patient cool. Move the patient to the shade of a tree, fan her, pour water on her head. Remove excess clothing. Have the patient lie down. If the patient is alert and able to swallow, give water; or, if you have it, Gatorade diluted three to four times; or about a half–teaspoon of salt dissolved in a quart of water, maybe with a pinch or two of sugar. Have the patient drink as much as a quart of water over the next hour. Recovery should be rapid and without consequences. If the patient does not improve promptly, then the condition may in fact be an early stage of heat stroke, and immediate evacuation should be seriously considered.

Always suspect heat exhaustion when a person becomes ill in hot conditions, especially during physical exertion, and particularly if accompanied by changes in level of consciousness. Heat exhaustion should be treated aggressively. More important, it should be prevented by drinking lots of water.

|

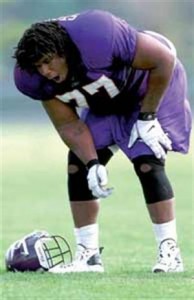

| Minnesota Vikings right tackle Korey Stringer died from heat stroke in 2001 |

The treatment for heat stroke is the same as the treatment for heat exhaustion. Cool the patient off as rapidly as possible. Remove excess clothing. Cover the patient with wet cotton clothing and fan vigorously. Apply ice if it is available, and at least pour the coldest available water over her. Concentrate on cooling the head and neck. It is probably not a good idea to try to immerse the patient in a river or stream, because a disoriented, combative, or convulsing patient is hard to manage and may drown. Do not delay. Be aggressive. You are saving a life. As the core temperature continues to rise, vital organs, such as the brain and kidneys, start to shut down. Cardiovascular and neurologic collapse are imminent. Evacuate immediately to where definitive care, including IV saline, is available, and continue cooling procedures during evacuation.

A few other points. Keep good records of vital signs, especially body temperature. The temperature may go down during cooling, and then rise again when you have stopped active cooling measures. If the patient becomes unresponsive, pay particular attention to keeping an open airway. If shock occurs, elevate the patient’s legs twelve inches.

Bear in mind that I am talking about wilderness emergency care, or care where resources are extremely limited — no ice, no normal saline, no IV start kit, no ambulance, no hospital. I will defer to others about urban street medicine, or patient management where such resources are readily available.

- Previous Post: Peyote Songs

- Next Post: The War on Coca Leaves Redux

- More Articles Related to: Jungle Survival

Gee, thanks I guess..

This makes going to sundance much more appealing!!

Also, according to my mother I have more mistakes than she can count. I always tell her that they all are manufacturing errors :)

I am sure there is some heat exhaustion at Sundance, but I wonder how many cases of heat stroke there really are. I would guess that the Sundance chiefs and elders have developed a pretty good sense of when things are beginning to go really wrong with a dancer. The same is true for sweats. I have heard of cases of heat stroke in sweats, always, as far as I know, with an inexperienced and self-appointed leader. Do you have any information on this?