I have always enjoyed reading certain writers — Gabriel García Márquez, Leslie Marmon Silko, Isabel Allende, Italo Calvino — whose works are often grouped together as magical realism. I think I know why. The world of these writers is, in a significant way, the world of the shaman, the visionary world, in which reality is interfused with the miraculous.

El realismo magical, lo real maravilloso americano, is deeply associated with the resurgent literature of South America, and is characterized by a detailed realism into which there erupts — in a way often experienced as unremarkable — the magical world of the spirits. Critics David Mikics, Derek Walcott, and Alejo Carpentier say that magical realism “projects a mesmerizing uncertainty suggesting that ordinary life may also be the scene of the extraordinary.”

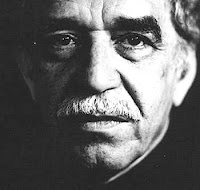

This idea is often expressed, as one commentator puts it, as “exploring — and transgressing — boundaries.” In a 1969 interview, Nobel Prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez said, of his own magical realist writings, ”My most important problem was to destroy the line of demarcation that separates what seems real from what seems fantastic. Because in the world that I was trying to evoke, that barrier didn’t exist.”

|

| Gabriel García Márquez |

Yet García Marquez describes himself as a realist writer, “because I believe that in Latin America everything is possible, everything is real.” Thus, in the fictional town of Macondo, Remedios the Beauty rises to heaven with her sister-in-law’s sheets. No reason is given, and her sister-in-law Fernanda does not wonder how this could happen. She accepts it without surprise, and only regrets that she has lost her sheets. My own plant teacher doña María Tuesta similarly was lifted to heaven inside her mosquito net to be initiated by the Virgin Mary. For her, too, this was wonderful and unsurprising.

Thus the visionary world does what literary critic Theo L. D’Haen calls “decentering privileged centers.” Magical realist texts — and thus the visionary world itself — are ontologically subversive. The magically realist world subverts the privileged ontological center that dichotomously divides experience into the real and the unreal.

|

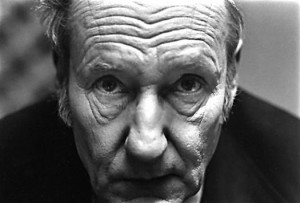

| William S. Burroughs |

Magical realism is often said to occur in places that postmodernist literary critics have called the zone. “The propensity of magical realist texts to admit a plurality of worlds,” write critics Lois Zamora and Wendy Faris, “means that they often situate themselves on liminal territory between or among those worlds — in phenomenal and spiritual regions where transformation, metamorphosis, dissolution are common, where magic is a branch of naturalism.” William S. Burroughs put it this way in a letter to Allen Ginsberg in 1955: “The meaning of Interzone, its space time location is at a point where three-dimensional fact merges into dream, and dreams erupt into the real world.”

This zone is the world of the shaman — the vision, the apparition, the lucid dream, seeing through the ordinary to the miraculous luminescence of the spirits, perceiving the omnipresent pure sound of the singing plants.

- Previous Post: The Natufian Shaman

- Next Post: Telling Dreams

- More Articles Related to: Books and Art, Shamanism