|

I talked here and here about a 1996 study of long-time users of ayahuasca in the União do Vegetal church, which showed that drinking ayahuasca hundreds of times over decades of participation had no adverse impact on personality, and was in fact associated with significantly higher scores on measures of concentration and short-term memory.

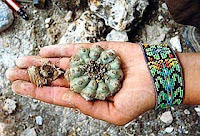

In 2005, a similar study of long-term peyote-using members of the Native American Church reported similar results. The study was funded by the National Institute for Drug Abuse and published in the journal Biological Psychiatry. Members of the Native American Church may attend ceremony as often as two or three nights a week or as infrequently as once a year, but most members attend, on average, one ceremony a month. Many ingest peyote hundreds or thousands of times in their lifetime.

The study involved three groups of Navajos aged 18 to 45 years old — 61 Native American Church members who reported ingesting peyote on a least a hundred occasions; 36 recovering alcoholics, sober at least two months, who reported a history of drinking more than fifty twelve-ounce beers or their equivalent per week for at least five years; and a comparison group of 79 persons reporting minimal lifetime use of peyote or any other substance.

|

All the participants were given a battery of ten nonverbal neuropsychological tests as well as the Rand Mental Health Inventory, a standard instrument used to diagnose psychological problems and determine overall mental health, including subtests that examine anxiety, depression, life satisfaction, and behavioral and emotional control. No significant differences were found between the peyote group and the comparison group on any of the neuropsychological measures. The peyote group also showed no significant differences from the comparison group on most scales of the RMHI, except that they scored significantly better than the comparison group on two scales that measure general positive affect and psychological well-being.

Moreover, within the peyote group, log-transformed lifetime episodes of peyote use showed no significant associations with neuropsychological measures, and were associated with significantly better scores on several RMHI measures. In other words, the more that people had participated in peyote ceremonies, the better were their mental health scores.

Of course, as with the União do Vegetal study, these results are associated with two potential causal factors — peyote use on the one hand, and, on the other hand, attendance at more than a hundred religious ceremonies. The study does nothing to disentangle these. But, again as with the União do Vegetal study, the results demonstrate that long-term peyote use in a ceremonial context certainly has no adverse effect on cognition or overall mental health. As the study states, “These findings suggest that long-term use of this hallucinogenic substance, at least when ingested as a bona fide sacrament, is not associated with adverse residual psychological or cognitive effects.”

|

The study includes a caution that these results cannot be generalized to other hallucinogens. “It is not clear whether our findings with peyote would apply to other types of hallucinogens,” the article states. “We cannot exclude the possibility that long-term use of chemically different hallucinogens (such as LSD or psilocybin) might produce adverse residual effects, even if peyote does not.” One of the authors of the study, in an interview, explained this concern. “The hallucinogens that are typically abused on the street by substance abusers are LSD and psilocybin, which is the principal component of mushrooms,” he said. “Those are indole molecules, and an indole is a different type of molecule from mescaline, which is the hallucinogenic component of peyote. So even if it is true that peyote has no long-term neuropsychological toxicity, you still cannot leap to the conclusion that indoles lack such toxicity.”

Of course, dimethyltryptamine, a hallucinogenic component of the ayahuasca drink, is just such an indole. Yet the peyote study surprisingly makes no reference to the União do Vegetal ayahuasca study, which, since it was published nine years earlier in the prestigious Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, seems hard to miss, and which might have gone some way toward addressing that concern.

- Previous Post: Ayahuasca and Cancer

- Next Post: Fire on the Mountain

- More Articles Related to: Research Studies, Sacred Plants, The Medicine Path

It has been my experience within my household which is a house hold of conditions that cactus in general I would consider healing plants. Opuntia greens are great for healing of the gut and relief of pain over long term use.This is now a common vegetable in our house replacing other forms of greens. The fruits of the Cereus balance hunger and blood sugar giving strength to finish a days work. Portions of the San Pedro gives mental balance to a disturbed mind filled with mental disorder. There seems to be no side effects in the cactus family of any kind but yet much better results than would be found in a drug store or pharmacy.