While it is apparently legal in the United States to possess the ayahuasca vine and its β-carboline constituents, it is clearly illegal to possess DMT, or any plants, such as chacruna, that contain DMT. Under Chapter 13 of the Controlled Substances Act, DMT is classified as a Schedule I drug, meaning the Drug Enforcement Administration has found that it has a high potential for abuse, has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and lacks accepted safety for use under medical supervision. A person who manufactures, distributes, or dispenses DMT, or possesses DMT with intent to manufacture, distribute, or dispense it, “shall be sentenced to a term of imprisonment of not more than 20 years.” Both the plant chacruna, and the ayahuasca drink that contains chacruna, have been held to fall within the scope of this prohibition.

So what happened with the União do Vegetal in the Supreme Court two years ago? A little legal history may be helpful.

On November 9, 1924, a Native American of the Crow tribe named Big Sheep was charged with the crime of unlawfully having peyote in his possession. The court refused to allow him to testify in his defense that he was a member in good standing of the Native American Church, or that members of that church used peyote “for sacramental purposes only in the worship of God according to their belief and interpretation of the Holy Bible, and according to the dictates of their conscience.” In remanding the case for further proceedings at the trial level, the Supreme Court of Montana noted that the Montana Constitution guaranteed the “free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship,” but pointedly observed that the liberty of conscience thus secured did not “justify practices inconsistent with the good order, peace, or safety of the state, or opposed to the civil authority thereof.”

There was absolutely nothing remarkable about that observation. The religion clause of the First Amendment reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Yet legislatures make laws all the time which can, under some circumstances, burden the free exercise of religion — laws against murder, for example, that implicitly prohibit human sacrifice. At the time of Big Sheep, the leading precedent in this area was Reynolds v. United States (1878), in which the United States Supreme Court had ruled that the Mormon religious practice of polygamy was not protected by the free exercise clause of the First Amendment — indeed, that the First Amendment offered no protection to any religious act that contravened generally applicable legislation. While Mormons were free to believe that polygamy was a religious duty, they just could not practice it — not because they were Mormons, but because no one could practice it.

This line of reasoning continued to be the model for First Amendment free exercise jurisprudence. In Prince v. Massachusetts (1944), the Court held that a woman was subject to prosecution for violating the child labor laws when she brought her nine-year-old niece with her to sell religious literature on a street corner; in Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), the Court upheld Sunday closing laws as applied to Orthodox Jewish businessmen who closed their shops on Saturday, rejecting the argument that forcing them to close their shops on a second day unduly burdened their religious practice.

However, beginning in 1963, the Court signaled a new approach to First Amendment religious issues. In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Court held that a state could not simply deny unemployment compensation to a person whose unavailability for Saturday employment was religiously motivated. Rather, the state had to show a “compelling state interest” for its refusal to grant a religious exception to the regulation. The Court said that “no showing merely of a rational relationship to some colorable state interest would suffice.” Only the gravest abuses, which endangered “paramount interests,” would allow the state substantially to infringe the free exercise of religion. And the Court followed up this new approach in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), holding that the state interest in compulsory education was not sufficient to justify the state forcing Amish families, against their religious principles, to educate their children beyond the eighth grade.

This new model of interpretation was first applied to peyote — by a state court, not a federal court — in People v. Woody (1964). The California Supreme Court, following the 1963 decision of the United States Supreme Court, overturned the conviction of several Navajo members of the Native American Church for possession of peyote. The court found that the state had not met its burden of demonstrating a “compelling state interest” to justify refusing a religious exemption to its drug laws.

The effect of this case was predictable. Soon people were lined up at the courthouse doors seeking religious exemptions for drug use — the Neo-American Church, the Church of the Awakening, the Native American Church of New York, and a whole slew of criminal defendants claiming that the marijuana for which they had been arrested was for use in their religious practice.

Not one of these claims for religious exemption for drug use was successful. Of all these claimants, only the Native American Church was able to establish a religious exemption to enforcement of generally applicable drug laws — and sometimes not even then. As late as 1975, an Oregon Appellate Court refused to find that the religious interests of the Native American Church outweighed legislative concern for “the health and safety of the people.”

Finally, in 1990, the United States Supreme Court slammed the door on the whole process.

Alfred Smith and Galen Black had worked as counselors for a private drug rehabilitation organization. They were also both members of the Native American Church, and they were fired from their jobs because they had ingested peyote for sacramental purposes at a church ceremony. When they applied for unemployment compensation, they were determined to be ineligible for benefits because they had been discharged for work-related misconduct. Both the Oregon Court of Appeals and the Oregon Supreme Court, following then-existing United States Supreme Court precedent, concluded two things — first, that the religiously inspired use of peyote fell within the prohibition of the Oregon statute, which “makes no exception for the sacramental use” of the drug; but, second, that such a prohibition was not valid under the Free Exercise Clause. Therefore, the State could not deny unemployment benefits to the respondents for having engaged in that practice.

So far, so good. But the United States Supreme Court reversed the Oregon Supreme Court — and, although the Court struggled to deny it, its own earlier precedents — and held that there was simply no religious exemption from laws of general applicability. As the Court put it:

To make an individual’s obligation to obey such a law contingent upon the law’s coincidence with his religious beliefs, except where the State’s interest is “compelling” — permitting him, by virtue of his beliefs, “to become a law unto himself” — contradicts both constitutional tradition and common sense.

Many commentators were surprised by what they perceived to be a sudden reversal of course by the Supreme Court. There was a perception that the Court, in jettisoning the requirement that the state show a compelling interest before abridging a religious practice, had abandoned marginal and quirky religions to majoritarian tyranny, in contravention of the spirit of the First Amendment. In response, Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (1993) (RFRA) — note the provocative title — which in effect enacted Sherbert into law.

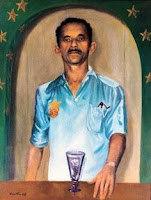

|

| Mestre Gabriel, founder of the União do Vegetal |

RFRA (pronounced refra) prohibits government from imposing a substantial burden on a person’s exercise of religion, even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability, unless the government can demonstrate that the burden is, first, in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest, and, second, the least restrictive means of furthering that interest. RFRA’s mandate applies to any branch of federal or state government, to all officials, and to anyone acting under color of law. The law is intended to apply to all federal and state law, and the implementation of that law, whether statutory or otherwise, and whether adopted before or after the date of RFRA’s enactment.

The passage of RFRA was the legal equivalent of Congress poking a sharp stick into the Supreme Court’s eye, and the Court responded accordingly. In City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), the Court held that RFRA was unconstitutional as applied to state and local governments.

The Court found that RFRA was a considerable congressional intrusion into traditional state and local prerogatives and general authority to regulate for the health and welfare of their citizens, and was not designed to identify and counteract state laws likely to be unconstitutional because of their treatment of religion. So, as of now, the protections of RFRA run against only the federal government, and do not temper the burdening of religious practices by the application of generally applicable state and local laws. If a Rastafarian is arrested for cultivating ganja in Topeka, Kansas, no matter how sincere his religious motivation may be, RFRA offers no protection.

The União do Vegetal (UDV) is a Brazilian new religious movement which utilizes the ayahuasca drink — which the UDV calls hoasca — in its church services. In 1999, federal agents raided the New Mexico home of a UDV church member who had three drums of ayahuasca. The officials seized the ayahuasca and threatened prosecution for possession of material prohibited by the federal Controlled Substances Act. In response, the church sued the U.S. Attorney General and other federal law enforcement officials, contending that the application of the federal drug laws to the religious use of ayahuasca violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Although RFRA had been declared unconstitutional as applied to states and municipalities, it was still binding on the federal government. And the UDV was not being prosecuted under the drug laws of any state; rather, its ayahuasca had been seized by the United States, and the UDV argued that the federal government could not articulate a compelling state interest in preventing its religious use of ayahuasca. The UDV sought an injunction requiring the federal government to give the church its ayahuasca back.

|

| Jeffrey Bronfman, Mestre Representante da União do Vegetal nos Estados Unidos |

The UDV had two important advantages. First, the UDV looks very much like a church of the sort with which an American court would be familiar — regularly scheduled ceremonies, a hierarchical structure, sober and orderly churchgoers, and a theology recognizably akin to that of Christianity. Indeed, a formal psychiatric study introduced at trial showed that long-term members of the UDV who consumed ayahuasca at least two times a month in religious rituals were, among other things, more reflective, loyal, stoic, slow-tempered, frugal, orderly, and persistent compared to controls. The ayahuasca-using participants also differed from the controls in being more confident, relaxed, optimistic, carefree, uninhibited, outgoing, and energetic, and with higher scores on traits of hyperthymia and cheerfulness. Significantly, on neuropsychological testing the UDV group demonstrated significantly higher scores on measures of concentration and short-term memory.

The second advantage was arguably even more important than the first. The president of the UDV in the United States was Jeffrey Bronfman, who is, unfortunately for the government, an heir to the Seagram’s whiskey fortune — the word bronfman means whiskey man in Yiddish — and second cousin to the profoundly well-connected Edgar Bronfman Jr., Chairman and CEO of Warner Music, among other things. Jeffrey Bronfman was a wealthy man in a powerful family, and he had the commitment and the resources to fight the seizure all the way to the United States Supreme Court.

And to the Supreme Court the case duly went, after both the trial court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit handed victories to the UDV, first by issuing a preliminary injunction against the U.S. Attorney General, the DEA, and other government agencies, requiring them to return the ayahuasca that had been seized from the group, and then by upholding the issuance of the injunction. On February 21, 2006, in a unanimous ruling, Justice John G. Roberts Jr. affirmed the trial court’s preliminary injunction preventing the federal government from enforcing a ban on the UDV’s sacramental use of ayahuasca. The Court held that the government had simply failed to demonstrate a compelling state interest in preventing the 130 or so American members of the UDV from practicing their religion.

Congress has determined that courts should strike sensible balances, pursuant to a compelling interest test that requires the Government to address the particular practice at issue. Applying that test, we conclude that the courts below did not err in determining that the Government failed to demonstrate, at the preliminary injunction stage, a compelling interest in barring the UDV’s sacramental use of hoasca.

Of course, the case is not over. All that has been litigated is the propriety of the initial preliminary injunction. There may yet be a trial, although the chances of an ultimate government victory over UDV appear to be slim.

- Previous Post: Shamans’ Organizations

- Next Post: Shaman of Colors

- More Articles Related to: Ayahuasca, Legal Issues

“While it is apparently legal in the United States to possess the ayahuasca vine and its β-carboline constituents, it is clearly illegal to possess DMT, or any plants, such as chacruna, that contain DMT. […] Both the plant chacruna, and the ayahuasca drink that contains chacruna, have been held to fall within the scope of this prohibition.”

Dear Dr. Beyer,

I believe this is not entirely correct, or rather incomplete. In other prosecutions, both the plant and the drink have been found to fall outside the scope of DMT prohibition. For the drink, the legal issue hinges on whether making a decoction of the leaves is equivalent to *extracting* DMT from them in the eyes of the law. Various state courts have come down on both sides of the issue. The current status of the drink in the USA would be best described as unclear. As for the chacruna leaves, prosecuting them is rendered more difficult by the fact that there are over 200 plants containing DMT, and over 30 of them grow naturally in the USA. Some of them apparently are commonly used as ornamentals.

Marco —

Your understanding is different from mine. The argument that chacruna leaves are legal, while DMT is not, has been rejected twice — by Judge Parker in the União do Vegetal case in New Mexico, and by Magistrate Judge Baverman in the Shoemaker case in Georgia. The Magistrate Judge found that the Controlled Substances Act, while not specifying the vines or leaves as illegal substances, covers “any material” that contains DMT. “When Congress speaks clearly, the court must follow what Congress has stated,” he wrote. I know of no ruling to the contrary; but if you can cite me a case, I would be happy to look at it. I personally think the argument is a loser, and I would hate to see people bet their freedom on it.

I posted an extensive response yesterday. Did it disappear in cyberspace? I could repost.

Marco

Marco —

I think your comment must have gotten lost in cyberspace. Usually comments pass through my email, and I didn’t see it. Please try reposting. Thanks.

That comment was based on memories of reading such an account in the legal section of the ayahuasca.com forum archives. I went back to rummage for it but couldn’t find it. It was most likely from someone presenting his wishes as fact.

It would be very interesting to me to be able to survey the outcome of all past prosecutions of both the leaf and the decoction. I just don’t have the research skills nor access to legal databases. Perhaps, since you have a legal background, you could help with that project or tell me how to go about it.

In the meantime, I withdraw this imprudent comment and I will agree with you – provisionally – that it is a loser argument.

I would add two points.

First, it remains true that DMT-containing plants are not rare. Here is a link to a sizable list:

http://www.drugs-forum.co.uk/forum/showthread.php?t=8680

Here is a shorter list of taxa containing DMT:

Acacia longifolia (Sydney golden wattle, golden wattle, long-leaved wattle, long-leaved acacia, sallow wattle, coast wattle, golden rods)

Acacia phlebophylla (Buffalo sallow wattle)

Anadenanthera colubrina (Yopo, Cohoba, Vilca)

Anadenanthera peregrina

Diplopterys cabrerana (Chaliponga)

Homo sapiens (human) Mimosa hostilis (Jurema)

Mucuna pruriens

Phalaris aquatica (Harding grass)

Phalaris arundinacea (Reed canary grass)

Psychotria viridis (Chacruna)

Virola calophyll

There is also a tiny seed or berry used in Chinese medicine. I bought some from a Chinese herbalist last year (they didn’t seem aware of the legal danger). Maybe a reader can recall the name.

The point being that if DMT-containing plants can be shown to grow a little bit everywhere, including in the gardens of politicians and judges, prosecution becomes highly impractical – not that there was much rationality in it to begin with.

Secondly, the distinction between the molecule and the plants containing it is made in the *international* conventions on drug prohibition currently in vigor. No individual country is obliged to follow that guideline in its internal laws, but if one did, it could lead to case

dismissals. Since it has become very possible that, starting in January 2009, the US government will become more inclined to join the concert of nations in global efforts and support international agreements – well, one should be allowed to dream.

Of course, the best protection in the US remains the constitutional rights granted to religions, as the UDV case showed. Thank God the country was founded by refugees from religious persecution.

A small addendum:

In 2001, a fax from the International Narcotics Control Board to the Dutch Justice Minister was apparently instrumental in the Santo Daime Church winning the right to practice in that country. The message affirmed the difference — in the view of the Board — between DMT the molecule and plant decoctions.

So in a hypothetical future with fewer rogue states (like France and the USA) with respect to international conventions, that could become a factor.

Steve Beyer wrote: “The effect of this case was predictable. Soon people were lined up at the courthouse doors seeking religious exemptions for drug use — the Neo-American Church, the Church of the Awakening, the Native American Church of New York, and a whole slew of criminal defendants claiming that the marijuana for which they had been arrested was for use in their religious practice.”

The Neo-American Church tried to claim LSD as their sacrament – the Church of the Awakening was Peyote.

The Native American Church of New York did not lose its case. In fact, they were the 1st organization to gain legal recognition that a non-American Indian has the same rights to worship Peyote as an Indian.